There's a plethora of coaching options in the marketplace along with a range of methodologies and outcomes. This piece cuts through the noise to examine what leadership coaching actually is, when it works best, and how it creates lasting impact.

Throughout I’ve linked to other articles that go deeper into specific aspects of leadership coaching.

(1) What Is Leadership Coaching?

Because coaching draws from a range of disciplines it can be hard to pinpoint and define it well. The following description from Robert Hicks captures many of the nuances:

Coaching is:

a Methodology: Coaching utilizes a person-centered, non-directive, inquiry-based methodology to assist clients in transformative learning and to construct solutions as a path to goal attainment. Through incisive questioning, the coach guides the client in critical reflection, self-discovery, self-directed learning, and problem-solving. This methodology imitates the Socratic method as it is a form of inquiry and discussion between the coach and the client. It is based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and illuminate ideas. It is not assumed that the coach has, or needs, expert knowledge about the subject matter for which the client is being coached.

a relationship: Coaching is a collaborative and egalitarian relationship between the coach and the coachee. Unlike an authoritative relationship, for example, teacher-student, the coach and the client are considered equal but have different roles. The client brings the agenda and has domain-specific expertise, while the coach brings know-how in the coaching process and relates to the client in the spirit of partnership. It is a powerful alliance – a professional collaboration – in which the client holds the ultimate responsibility for and ownership of the desired outcomes.

a purpose: Coaching deals with a wide range of conventional, non-clinical issues. Its purpose is not to promote emotional healing or relief from psycho- logical pain, such as that accompanying clinically significant mental health problems. Instead, its purpose is transformative learning to enhance the client’s life experience as well as personal and professional goal attainment. The coach is trained in and devoted to guiding others to optimize their potential, performance, and happiness.

a philosophy: Coaching is a philosophy of empowerment. It is a philosophy built on the premise that clients bring a foundation of life experiences and knowledge they can draw upon to solve their problems, make decisions, and reach their goals and objectives. With help from their coach, clients use their resourcefulness, skills, and confidence to find solutions to problems and pathways to goals. It is believed that answers come from within the client. Therefore, clients are encouraged and expected to take charge of their lives and be responsible for their choices.

a process: Coaching is a process of supporting and challenging clients so that they are encouraged to learn, discover, understand, and solve problems independently of the coach. The process is heuristic and favors experiential learning whereby the client engages in critical reflection, evaluates possible answers or solutions, and then experiments to gauge the efficacy of those solutions. Some experiments might be purely exploratory, with actions taken only to see what follows. Others might be performed to initiate change, and others to test hypotheses. It is a process in which a coach and client work together utilizing the mediums of inquiry, deliberation, and dialogue.

He adds:

In the parable about the blind men and the elephant, each part of the elephant does not, by itself, provide a complete picture of the elephant; it is the same with each facet of coaching. Separately, they do not define coaching entirely or distinguish it from other helping conversations, but collectively, they answer the question, “What is coaching?”

— Robert Hicks in The Process of Highly Effective Coaching

Leadership coaching in particular is often mistaken for advice-giving, mentoring, or training. In reality, it’s none of those. At its core, it's a deliberate, structured process designed to expand your capacity as a leader. Instead of handing you answers, it sharpens the way you see problems, frame choices, and mobilize others.

Where training builds skills and mentoring shares experience, coaching works at the level of judgment, perspective, and meaning-making. You’re building a stronger operating system rather than adding more apps. You already know how to “do” your job. The missing piece is the ability to interpret complexity, make better calls under pressure, and translate your impact across different arenas and constituencies.

Leadership coaching isn’t about fixing deficiencies either. It equips you for the demands of modern leadership which requires you to go beyond technical expertise and functional competence. Today’s leaders operate inside shifting contexts, paradoxes that can’t be solved, and contradictions that don’t resolve neatly.

Coaching is the space where you learn to skillfully navigate these forces instead of being blindsided by them.

Related: Conceptual vs experiential learning

The Spectrum of Leadership Coaching

When people say “coaching,” they often mean very different things. The spectrum runs from surface-level skill tuning to deeper developmental shifts. What changes isn’t just the method, but the unit of development itself.

At the most basic level, coaching is about skills and is behavioral. You learn a new technique — how to run effective meetings, how to frame feedback, or how to prioritize efficiently. The impact is immediate but narrow. It helps correct a visible weakness or sharpen a specific competency. It’s bounded, concrete, and measurable.

Performance coaching moves up a level. Now the work is less about discrete skills and more about sustaining execution under pressure. Here coaching is not about “what to do” but helping you do what you already know more consistently. The aim is fewer dips, less reactivity, and more reliable performance. Here the unit of development is execution.

At the highest level, coaching becomes developmental. The unit of progress here is your sensemaking capacity: how you frame problems, interpret signals, and exercise judgment in unfamiliar territory. The focus is not on fixing a problem but on building who you are as a leader. Developmental coaching stretches your interpretive range. Unlike skill tweaks or performance upgrades, it works on the foundation, is further upstream, and changes how you think, not just what you do.

Most leaders initially come in seeking skills or performance. What sustains growth however, is developmental work. It’s the difference between tightening the bolts on the same machine versus redesigning the operating system that drives it.

The three levels form a continuum: Skills → Performance → Developmental. The orientation moves from what you do → how you do it → how you make sense of it all. A coaching engagement may touch all three, but the weight shifts depending on the leader’s context.

Related

(2) Why Leadership Coaching Matters Today

In the last 50 years, the context for leadership has shifted. The old playbook — technical expertise, clear hierarchies, predictable problems — no longer fits the reality most leaders face. Modern organizations today are flatter, more interdependent, and constantly in flux. The result is that leaders aren’t just solving problems; they’re navigating messes.

Leadership coaching helps leaders break out of the tyranny of control: the endless drive to consume more tactics and strategies—without realizing the real challenge is context. The bottleneck isn’t knowledge but making sense of the situation in front of you, aka leadership sensemaking.

Coaching isn’t a nice-to-have support system. It’s one of the few spaces where you can slow down, reframe, and work on the muscles that leadership actually demands. This includes judgment, framing, communication, courage, and power, amongst several others. Without this, you risk mistaking busyness for progress. Or doubling down on what made you successful in the past, even while the game itself has changed.

Most leadership advice still treats the role as one-dimensional. But once you’ve moved past early management, it’s no longer enough to simply know your craft or deliver results within your lane. Leadership stretches across three interlocking dimensions, each with its own demands. Think of it as operating on three levels simultaneously of skill, savvy, and sensemaking:

- Functional expertise — delivering results through your technical skills.

- Organizational savvy — navigating politics, perception, and influence.

- Leadership sensemaking — making sense of unclear situations and guiding others when the path forward isn't obvious.

These layers rarely develop at the same pace. Most leaders excel in functional competence while lagging in the other two. The result is unfortunately predictable: leadership derailment, or frustration when old approaches stop working.

Instead of treating leadership as a checklist of skills, coaching recognizes it as an evolving capacity to balance and integrate these competing demands.

Related

(3) How Leadership Coaching is Different

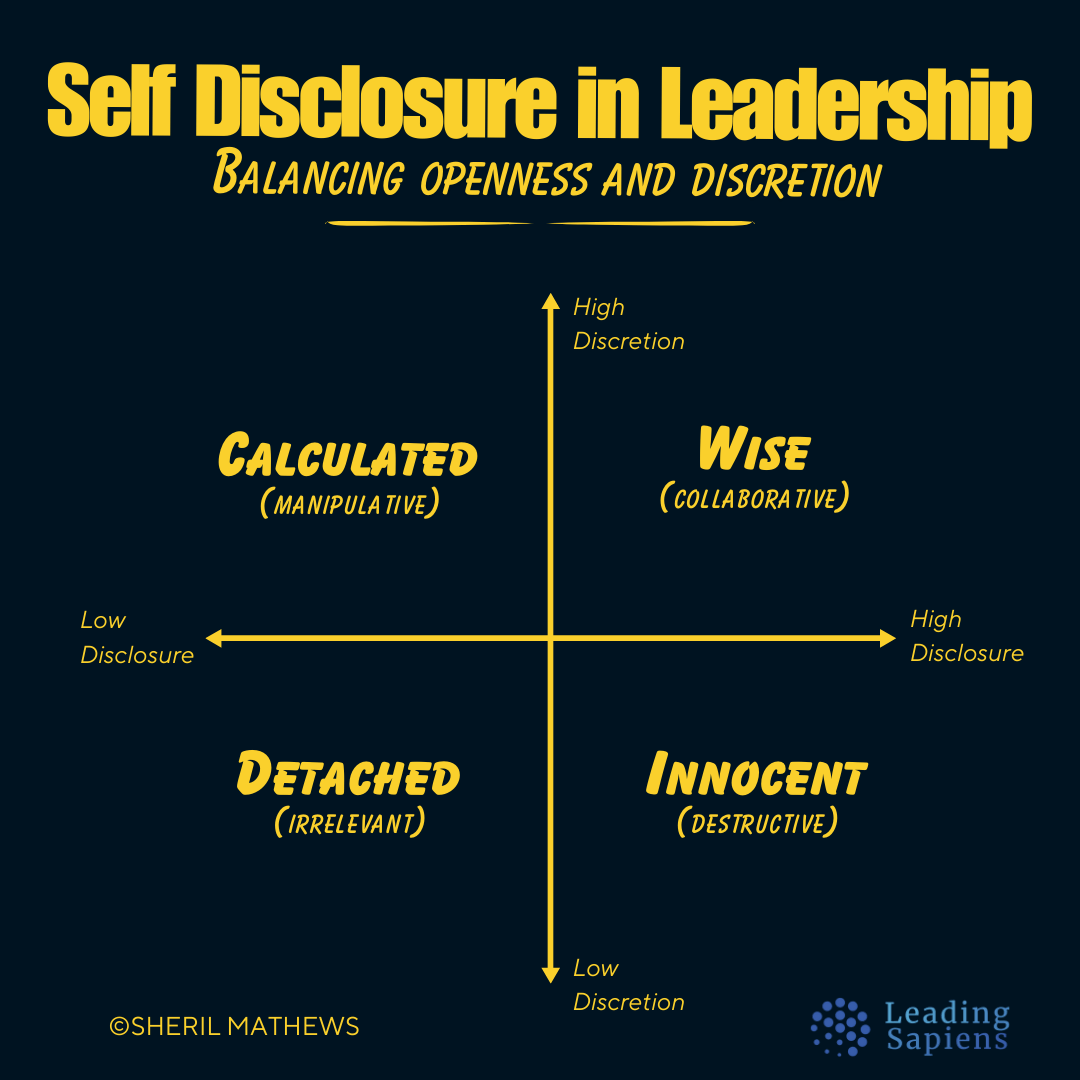

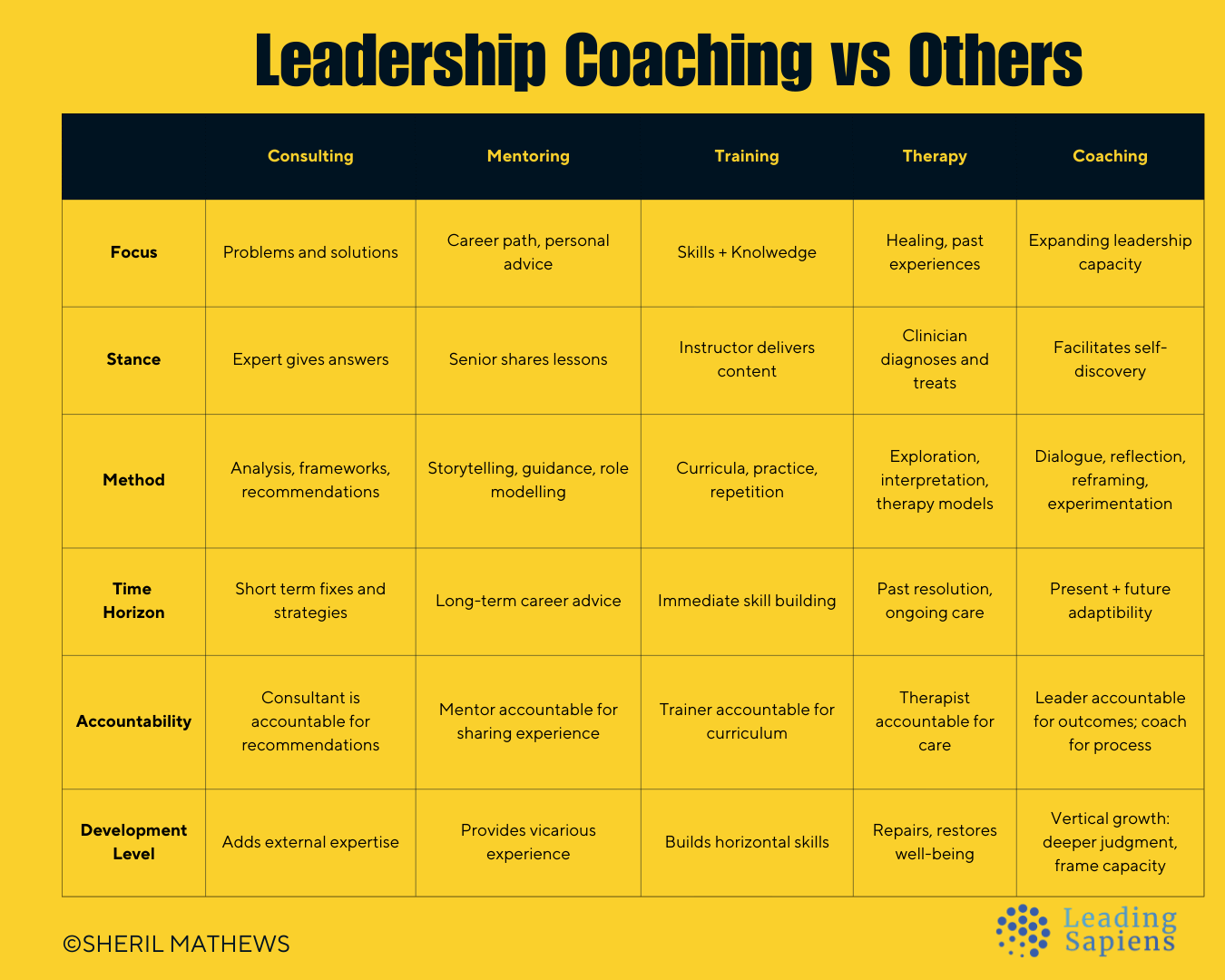

One of the reasons leadership coaching gets misunderstood is that it resembles other forms of professional support. On the surface, it may look like consulting, mentoring, training, or even therapy. But the purpose, stance, and methods are very different.

Consulting gives you answers. You pay for expertise to be delivered, often in the form of recommendations or frameworks. A consultant is accountable for the content. A coach, by contrast, is accountable for the process that helps you generate your own insights and action.

Mentoring is wisdom passed down. A mentor shares their own career playbook and lessons learned. Valuable, yes—but limited by the mentor’s path, a sample size of one. Instead of handing you a script, leadership coaching sharpens your judgment so you can write your own.

Training builds skills. Think of it as horizontal development: adding more tools to your kit. Coaching is vertical development: upgrading the lens through which you choose which tools matter, and how to use them.

Therapy helps you process the past and heal. Coaching looks forward. It’s less about resolving trauma and more about expanding capacity to navigate complexity, uncertainty, and pressure.

A useful way to see this is as a continuum from content-driven (consulting, training) to context-driven (coaching). The closer you get to coaching, the more the emphasis shifts from answers to awareness, from transferring knowledge to transforming how you make sense of challenges.

Coaching Builds Leadership Capacity, Not Just Competence

When people talk about leadership development, they often mean competence — building specific skills like delegation, communication, or decision-making. Competence is important, but also limited because it lives at the technical level: learn a tool, apply it, repeat.

Capability goes a step further. It’s being able to execute well under real conditions. A capable leader can manage complexity, juggle competing demands, and still deliver results. Most organizations stop here.

Coaching goes much farther. It’s about capacity — the ability to grow the container itself. Instead of just pouring in more tools or sharpening existing abilities, capacity asks: how much weight can you hold? How wide is the lens through which you see the problem? How many perspectives can you keep in play before defaulting to old habits?

This matters because leadership is not defined by static skills, but by the ability to expand into ever-wider demands. Coaching helps you develop the inner structure — judgment, sensemaking, systemic awareness — that makes you capable of handling situations you’ve never seen before.

Skills might solve today’s challenges but its capacity that equips you for tomorrow’s unknowns.

Related: Ladder of Inference in Decision Making

Training Leaders vs. Building Leadership Capacity

Most organizations still default to training when they talk about leadership development. Training is about the transfer of information: teaching models or prescribed behaviors hoping you'll apply them as situations arise. It works well for technical skills, where the path from knowledge to execution is clear.

Coaching works differently. Instead of focusing on what to do, it develops your capacity to navigate complexity. Where training equips you to apply solutions, coaching prepares you to frame problems in the first place.

This difference is crucial. Modern leadership demands more than functional competence. You need to work across systems and mobilize others when the way forward isn’t obvious. Training rarely addresses these adaptive challenges. Coaching helps leaders grow the capacity to meet them.

Related

Coaching helps build practical judgment

Too often, coaching is reduced to a repair function that leaders seek when there’s a visible problem to solve. But the real value is not in patching holes; it’s in sharpening judgment. Leadership isn’t a sequence of problems with correct answers. It’s a steady stream of ambiguous situations where context shifts faster than the playbook.

Good coaching develops your ability to size up these situations, notice what matters, and act responsively. That’s practical judgment: the ability to choose well under uncertainty. A coach helps you slow down, examine assumptions, and weigh alternatives you might otherwise miss.

This is why coaching belongs less to the world of technical “fixes” and more to the realm of cultivating discernment and judgment. Instead of operating on recycled advice, you draw from a deeper well of perspective you built.

Leadership is learnable, not teachable

Leadership isn’t something that can be handed over in a neat package. You can sit through programs, read case studies, and memorize frameworks. They’ll give you concepts and language but what they can’t give you is judgment.

Skills can be taught; but not sensemaking.

Judgment is built the hard way through experience that’s been worked over, not just lived through. You learn it by doing, reflecting, reframing, and trying again. That cycle is what turns raw events into leadership capacity.

Only practice shows you what fits here, now, with these people. Coaching accelerates that process by helping you see patterns, recover quicker, and translate experience into more calibrated responses.

Related

Return on Experience

Years in a role don’t automatically translate into growth. Most folks repeat the same year twenty times. Only a select few compress twenty years of growth into a decade. The difference lies in how experience is metabolized.

Experience as raw material. What matters isn’t the volume of situations you’ve faced but the way you process them. Left unexamined, experience calcifies into habit. Examined with discipline however, it becomes judgment. Coaching accelerates this conversion by turning raw encounters into refined capacity.

Beyond repetition. High performers often assume sheer exposure will keep them growing. But exposure without reflection produces diminishing returns. Coaching inserts the missing loop using structured reflection, reframing, and testing new mental models. That’s how leaders avoid plateauing despite years of “experience.”

ROI here doesn’t mean squeezing more productivity out of the same hours. It means converting the inevitable costs of leadership—failures, frictions, missteps—into dividends of wisdom. Coaching ensures your toughest stretches compound rather than deplete.

(4) When Leadership Coaching Has the Most Impact

Role Transitions and Scope Expansion

Leaders usually don't seek coaching when things are smooth. They seek it when the ground shifts—when the game changes and the rules they've relied on no longer apply.

Role transitions. Moving from individual contributor to manager, or from manager into more senior roles, is less about climbing a ladder and more about switching games entirely. The unit of work changes. You move from delivering tasks to influencing outcomes, from providing answers to framing questions. What made you reliable in the last role makes you rigid in the next. The challenge is not effort, but perspective.

New mandates. A turnaround, a reorg, or a high-visibility project comes with both the written and unwritten challenges. The explicit expectations are difficult enough. The implicit ones — speed, politics, optics — are where leaders stumble. What's really at stake is your ability to read the situation correctly. Misinterpret or mis-frame the mandate, and even good execution looks like failure.

Scope expansion. The further you rise, the more your effectiveness depends on others. Paradoxically, you also directly control much less. The boundaries widen, interdependencies multiply, and leverage shifts from effort to influence. Those who continue to rely on technical horsepower eventually find themselves overextended. What's required is organizational savvy — understanding how different types of power and perception shape outcomes — and sensemaking: the ability to frame choices in ambiguity.

What really changes. The language of the work moves from tasks and timelines to narratives and trade-offs. The unit of impact shifts from your individual contribution to how the system as a whole moves. And the judgment calls stop being clear-cut and start being paradoxical—you are now holding contradictions rather than resolving them.

Diagnostic signals. You hear feedback like "be more strategic" or "you need more executive presence" without specifics. Your core strengths — expertise, urgency, detail — have become a liability. You're doing more but with reduced to no real impact.

At these thresholds, the issue is rarely competence. It's a lot about framing and sensemaking. Coaching slows the rush to solutions and works first on the underlying lens: What game are you in now? What counts as winning? Only then does the work move to practices—reflection cadences, decision hygiene, and influence strategies—that allow you to operate at the new altitude.

Related

The High-Performer Paradox

High-potential leaders are often promoted because of exceptional performance. But what earned the label "Hi-Po" can become the very thing that limits them once the scope widens.

Over-reliance on competence. Many Hi-Pos rise by outworking and out-solving. They know the details, anticipate problems, and deliver reliably. But leadership is less about having the right answers and more about cultivating the right questions. When technical competence is overused, it creates bottlenecks: everything flows through you.

The hidden trap. High performers are accustomed to linear effort: input equals output. Leadership breaks that equation. More effort doesn't guarantee more impact. Sometimes it even backfires—micromanagement, over-control, or taking on too much dilutes both your effectiveness and your team's.

Adaptive demands. What distinguishes leadership is not speed or efficiency but adaptability. The real challenges are ambiguous, political, and paradoxical. Hi-Pos hit ceilings not because of lack of ability, but because they keep applying technical solutions to adaptive problems.

Identity strain. For many Hi-Pos, leadership advancement feels like a loss. You move further from the craft that defined your identity. The source of past success—the ability to "do"—is now precisely what you must give up. This identity gap creates resistance, even self-sabotage.

Coaching interrupts the automatic loop of "do more, try harder." It builds the reflective space to reframe effort, identity, and value by shifting the focus from proving competence to building capacity.

Related

- Creative vs Controlling Leaders

- Leadership as a decision

- Drivers of human performance

- Developing your leadership identity

Adaptive vs. Technical Challenges

Not all problems in leadership are created equal. Some are technical: the problem is clear, the solution is known, and the task is execution. Others are adaptive: the problem is murky, the solution is undefined, and progress requires shifts in beliefs, habits, and priorities.

This distinction is one of the most important and most overlooked lenses for leaders. Technical fixes are seductive because they feel concrete. You can hire an expert, buy software, or tweak a process. Adaptive challenges, by contrast, ask you to change how you see, how you decide, and often how you lead yourself.

Leaders derail when they treat adaptive challenges as technical ones. They double down on expertise, demand playbooks, and search for best practices—when what's really needed is new capacity to hold tension, tolerate ambiguity, and orchestrate learning.

Coaching is uniquely suited here. Unlike training, which delivers more tools, coaching develops your ability to diagnose what kind of problem you're really facing. It helps you avoid the trap of working harder on the wrong category of challenge.

If you find yourself repeating the cycle of "we fixed it, but nothing really changed," you're likely bumping up against adaptive terrain. The leverage isn't in smarter answers but in better framing of the problem itself.

Derailment Prevention and Performance Spirals

Every leader eventually runs into ceilings. Not ceilings of intelligence or effort, but of perspective. What worked before stops working—not because you've lost ability, but because the game has changed.

From strengths to overdrive. The very traits that fuel early success—decisiveness, persistence, mastery of detail—can, at scale, tip into rigidity, impatience, or micromanagement. When strengths are unexamined, they morph into derailers.

Blind spots widen with scope. As responsibility grows, so does exposure to complexity and ambiguity. But leaders often double down on familiar habits rather than expand their range. This creates a widening gap between what the role demands and how they show up.

The slow unravel. Derailment rarely happens in a dramatic fall. More often it's a gradual erosion: relationships fray, trust thins out, and teams disengage. The leader may still appear "successful" on paper while the organization quietly adapts around their limitations.

Performance spirals are real. Once you start slipping, the system reinforces the slide. Stress leads to rushed judgment. Rushed judgment creates errors. Errors trigger more scrutiny, which fuels more stress. Before long, a capable leader looks like they're "not ready for the role."

The hidden trap. What makes these spirals dangerous is that they masquerade as temporary dips. Leaders tell themselves: I just need to push through this quarter. Except pushing through often accelerates the downward loop—fatigue, tunnel vision, and reactive decisions stack up until the narrative about you changes.

Coaching surfaces these patterns early, before they calcify into derailers. It creates the space to notice overextensions, question assumptions, and experiment with new frames. Coaching doesn't prevent ceilings—it helps you recognize when you've hit one, and equips you to break through without burning out.

Related

Cognitive Overload and Competing Demands

Modern leadership isn't about managing time. Rather, it's managing attention under assault. Information flows faster than you can process. Everyone wants a piece of you. And each comes with a different level of urgency and "what matters."

The bandwidth trap. Many leaders treat capacity like a brute-force problem: work longer, push harder, sleep less. That's simply not sustainable. Overload doesn't just drain energy; it narrows vision. Under pressure, you default to the familiar, even when the situation demands the opposite.

The illusion of juggling. The higher you go, the more contradictory the pulls. Short-term delivery vs. long-term positioning. Driving execution vs. cultivating culture. Saying yes to one means saying no—sometimes invisibly—to another. What looks like "balancing" is often just constant trade-offs, made without reflection.

Coaching forces the pause. It's not about adding more tools to an already overflowing plate. It's about sharpening discernment—knowing which demands deserve attention, which can be reframed, and which should be dropped entirely. Leaders rarely fail because they didn't try hard enough. More often, they fail because they misallocated their focus.

Related

- Cognitive Distortions in Leaders

- Cognitive flexibility: Rewiring How Leaders Respond

- Negative capability

(5) How Leadership Coaching Works

The mechanics of leadership coaching are deceptively simple. On the surface, it is a series of structured conversations. But underneath, it's a cyclical process designed to shift how you see, think, and act.

It begins with scoping. Together, we identify the thresholds you're standing on — maybe it's a role transition, a widening span of control, or a recurring blind spot. Instead of "fixing problems", it's mapping out and identifying where your current ways of operating aren't working.

From there, coaching moves into cycles of practice and reflection. Each conversation is a process of surfacing assumptions, testing interpretations, and experimenting with new approaches in the real world between sessions. The real work happens in the messy middle of your daily leadership, and the coaching cycle creates a rhythm for extracting lessons from it.

The third step is integration. Insights only matter if they change how you operate. Coaching helps translate reflection into real-world behavior, decisions, and conversations. This is where knowledge changes into embodied capacity.

Over time, these loops build momentum. Scoping sharpens focus, cycles generate learning, and integration cements capacity. What looks like a series of conversations is in fact learning architecture: a structured yet adaptive process for building the kind of judgment and presence that can't be picked up in a classroom.

Container and Catalyst

The container matters because leadership roles rarely offer a protected place to think out loud, test half-formed ideas, or surface doubts without consequence. Inside a coaching engagement, you get that boundary: structured enough to focus, but loose enough to explore. It absorbs the noise of daily demands so you can hear yourself more clearly.

But the container on its own is insufficient. Coaching is also a catalyst; it doesn't just help your thinking, it accelerates it. The simple act of having someone track your patterns, reflect them back, and press into the unasked question compounds learning in ways solo reflection can't. It sharpens judgment, speeds frame shifts, and forces attention to what normally stays at the margins.

The interplay is what makes it powerful. Too much container without catalyst becomes therapy, safe but static. Too much catalyst without container becomes advice, fast but shallow.

Related

Reflection as Method

At its core, coaching is a structured process of reflection that's both disciplined and deliberately tied to action.

Kolb's learning cycle of going from experience → reflection → conceptualization → experimentation is illustrative here. Leaders often live in the first and last stages, piling up experiences and then rushing into the next action. Coaching forces attention to the neglected middle, where raw experience is digested into usable insight. Without this, you don't grow, just repeat.

And then there's deliberate practice, borrowed from sports and performance domains. Reflection turns everyday leadership moments into practice fields. The difference is in the feedback loop. Instead of vague lessons, you're breaking down moves, testing alternatives, and embedding improvements consciously.

Done right, reflection in coaching is how leaders metabolize the chaos of their roles into learning.

Related

Double-Loop Learning and Premise Transformation

Most leaders operate in what Chris Argyris called single-loop learning: you try something, it doesn't work, so you adjust your tactics.

Coaching works in the deeper lane of double-loop learning. Here, the questions shift from "Did I do it right?" to "Am I even solving the right problem?" and "What assumptions underlie how I'm seeing the problem?"

This is where premise transformation comes in. Every leader carries hidden premises about authority, risk, time, or even what "good leadership" looks like. Most of these aren't chosen but instead inherited, absorbed, or silently assumed. Coaching surfaces them, stress-tests them, and if needed dismantles them.

Imagine leaders who believe "decisiveness means never changing your mind." In a single-loop frame, they just try to make quicker decisions. In double-loop coaching, the premise itself is challenged: what if revisiting a decision is not weakness but higher-order adaptability? This opens an entirely different repertoire of responses.

Once leaders start revisiting their premises, they often realize that some of the hardest problems they face aren't technical missteps but frames that no longer fit.

Building Frame Capacity and Judgment

At its core, leadership coaching is about expanding the way you see. Most leaders fail not because they lack intelligence or technical competence, but when their framing of situations is too narrow. They over-rely on one habitual lens, misread context, or mistake technical puzzles for adaptive problems. Coaching helps to stretch this interpretive range.

Think of this as building frame capacity. Can you shift between strategic, political, relational, and systemic perspectives? Can you recognize when the problem is one of execution versus one of meaning? Those who can hold multiple frames in tension, and know when to privilege one over another, consistently make better calls under pressure.

From that expanded framing grows something harder to pin down but more valuable: judgment. Unlike competence, judgment can't be taught through a workshop or checklist. It's cultivated in the messy back-and-forth of experience, reflection, and feedback. Coaching accelerates that process. In conversation, your assumptions get tested and blind spots become visible. You start making sense of complexity instead trying to eliminate it.

Coaching is one of the few spaces where you can rehearse judgment without the steep costs of failure.

Related

(6) Different Approaches in Leadership Coaching

Not all coaching looks or feels the same. Three broad traditions tend to show up in leadership coaching:

- Psychological. This is where coaching borrows from counseling and psychology. It focuses on self-awareness, emotional regulation, and the hidden assumptions that drive behavior. For example, unpacking self-doubt, identity, or the implicit leadership theories that shape how others see you.

- Behavioral. Rooted in performance and habit science, this approach emphasizes observable action. It's about practice, feedback, and iteration. Think deliberate practice, goal-setting, and shifting daily routines so that leadership behaviors become repeatable.

- Systemic. Here the focus is less on the individual in isolation and more on the leader in context. How do power, structure, culture, and relationships shape what's possible? A systemic approach works on frames, organizational dynamics, and the leader's influence within the larger system.

In practice, good coaching blends these. A purely psychological focus risks becoming therapy-lite. A purely behavioral focus risks being too narrow, addressing symptoms but not causes. And a purely systemic view can neglect the inner shifts required to act differently. The leverage comes from working with all three perspectives.

My Coaching Focus

Every coach emphasizes different leverage points depending on their training, philosophy, and experience. Some lean heavily on assessments. Others focus on goal-setting mechanics.

My approach is not about fixing performance gaps in functional skills. If you've made it this far in your career, you already know your craft. Where leaders stall is not in doing the work but in making sense of the work. This means framing problems, navigating power, influencing without authority, and holding paradoxes.

That's why my coaching centers on two pillars:

- Organizational Savvy – how you position yourself, work with power, and navigate inside complex structures. This is the political and relational terrain where careers are made or quietly capped.

- Leadership Sensemaking – how you interpret complexity, reframe problems, and develop judgment under uncertainty. It's the meta-skill that gives leverage across situations and scales with you as your scope grows.

These are not "nice to have" extras. They are the multipliers that determine whether your functional expertise translates into real authority and impact. I don't focus on teaching functional competence — you already have that. Instead, my work targets the higher-order skills that let you extend your reach, sharpen your judgment, and adapt under pressure.

These are meta-skills that act as durable capabilities you can take into every role, transition, and arena.

Related

(7) Outcomes and Impact of Leadership Coaching

When you enter coaching, you should expect clarity, not magic. Coaching is neither a quick fix nor an endless excavation of your psyche. The outcomes follow a layered pattern:

Early on, expect clarity. Most leaders experience coaching first as a release valve. The noise quiets, priorities sharpen, and blind spots start to reveal themselves. It’s less about learning something new than about noticing what you’ve been missing.

In the medium term, expect re-framing. Coaching shifts the way you narrate your role — from executing tasks to shaping context, from proving competence to exercising judgment. You begin to see where your performance plateaus were actually limits of perspective.

In the long run, expect self-sufficiency. The real outcome isn’t dependency on a coach but the ability to coach yourself and self-correct: recognizing your own distortions, catching unhelpful patterns, and generating better frames for complex problems. Coaching done well makes itself redundant over time.

The process is conversational but not casual. Expect a mix of inquiry and challenge. Some sessions will feel catalytic, others more like incremental tuning. Both matter. The small recalibrations accumulate into small wins that build momentum.

What you should not expect:

- A ready-made toolkit of answers.

- Transformation overnight.

- Someone else carrying the burden of your decisions.

Good coaching helps you wrestle with the right problems, not escape them. It sharpens the edge of your own judgment, rather than dulling it with borrowed wisdom.

Organizational Outcomes

Coaching is often framed as a private, one-to-one intervention. But its real test is in how individual shifts in leaders reverberate through the organization. A coached leader doesn’t just think differently; they set different conditions for others. And those conditions, over time, shape culture and strategy execution.

At the organizational level, leadership coaching operates on three planes:

- Alignment with strategy. Coaching helps leaders link their personal development directly to the strategy their organization is trying to execute. This prevents the common disconnect where leaders grow in ways that are interesting but not necessarily useful to the business. For instance, a leader navigating a digital transformation needs more than generic “confidence building.” They need to practice reframing complex tradeoffs, interpreting cross-functional dynamics, and aligning teams around ambiguous goals. Coaching builds that connective tissue.

- Cultural Ripple Effects. Leaders set the tone. When they model reflection, curiosity, and adaptive learning, others follow. A coached leader creates a subtle but powerful ripple: meetings run differently, conflict is handled with more nuance, conversations open up. These may seem small, but over time they accumulate into a culture that is either brittle and defensive, or open and resilient. Coaching accelerates the latter.

- Systemic Resilience. Coaching is not just about better decisions today; it’s about building organizational capacity to handle tomorrow’s complexity. Leaders who expand their ability to see problems through multiple lenses make it easier for their organizations to avoid tunnel vision and over-reliance on single solutions. This translates into more robust execution and greater adaptability when conditions shift.

Evidence and Research on Coaching Impact

Leadership coaching has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry. But what does the research actually say?

The strongest body of evidence points to behavioral transfer and performance outcomes. Meta-analyses and longitudinal studies consistently show that coaching improves goal attainment, enhances leadership ability, and strengthens emotional intelligence. Unlike many forms of leadership training — where knowledge fades once the workshop ends — coaching’s one-to-one structure creates accountability for real-world application. Leaders don’t just learn frameworks; they test them in live contexts, then return to reflect and recalibrate.

Another theme is retention of high potentials. Organizations that invest in coaching signal to their most capable leaders that they matter, which reduces attrition. Coaching also addresses the “Hi-Po paradox”: high performers are often at greatest risk of derailment when promoted. Research shows that timely coaching support reduces failure rates in critical transitions.

There’s also growing evidence that coaching supports systemic outcomes: improved team performance and a healthier work environment. This happens through the ripple effects of coached leaders modeling better conversations and steadier judgment under pressure.

But coaching is not a cure-all for broken systems, poor strategy, or toxic cultures. Its effects are strongest when combined with organizational support and aligned with strategic priorities.

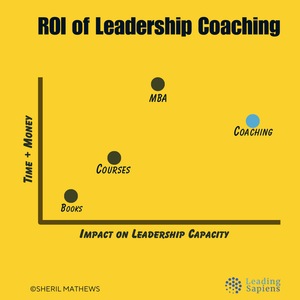

ROI of Coaching

When organizations ask about coaching, the default question is: What’s the ROI? Did it save money, improve retention, boost revenue? Those are fair questions. But they’re also incomplete. Leadership coaching operates in a domain where the most valuable returns aren’t purely financial.

Think in terms of ROI vs ROE — Return on Investment vs Return on Experience.

ROI (Return on Investment) is the traditional, quantifiable lens. Metrics include promotion rates, improved performance scores, reduced turnover, or shortened time-to-productivity after role transitions. Studies and case reports show coaching pays back multiple times over in these terms, especially when compared with one-off training.

ROE (Return on Experience): This is where coaching shines but often gets overlooked. The value lies in the leader’s ability to metabolize difficult experiences into lasting growth. ROE shows up as:

- Navigating critical transitions without derailment.

- Building capacity for paradox and ambiguity.

- Judgment and frame-shifting skills that compound over a career.

- Moving from repeated vicious cycles (overload, firefighting, burnout) to sustained virtuous ones.

What distinguishes ROE is that it accumulates. Each cycle of coaching creates durable experience leaders can draw on again and again. Unlike ROI, which is tied to a fiscal quarter or performance cycle, ROE continues to pay back long after the coaching engagement ends.

This is also where leadership development connects to strategy. Well-coached leaders have an impact far beyond their immediate role. The experience returns ripple into team resilience, cultural norms, and organizational adaptability.

(8) What Leadership Coaching Cannot Do

Leadership coaching is powerful, but it’s not magic. One mistake is to approach coaching as a cure-all. When you’re in the thick of complex challenges, it’s easy to project every frustration onto the process, expecting coaching to fix the system, the team, or the organization itself. That’s not what coaching does.

Coaching cannot change broken structures or bad incentives. If the organizational architecture is flawed no amount of individual growth will override that. Coaching equips you to navigate those realities with clarity and creativity, but doesn’t dissolve them.

It's also not a substitute for training. If what you need is a technical skill — finance modeling, regulatory expertise, data analysis — you get help from a course, mentor, or direct practice. Coaching complements those by helping you integrate knowledge into judgment, but it won’t give you domain specific knowledge.

Nor is coaching therapy. While reflection, self-awareness, and emotional growth are central to the process, clinical issues or unresolved trauma require a different container. Coaching may surface such matters, but responsible coaches recognize the boundary and refer appropriately.

Finally, coaching is not consulting. A consultant parachutes in with a diagnosis and recommendations. A coach doesn’t hand you answers; they help you sharpen the way you frame problems, test assumptions, and generate solutions. The value lies not in importing expertise, but in strengthening your own capacity to decide, act, and learn.

Thus coaching is leverage, not a panacea. It extends your range as a leader. It doesn’t do the work for you, neither does it eliminate the constraints of organizational life. It does however make you more capable within those constraints by turning them from barriers into the conditions where leadership is tested and built.

Leadership coaching is a long-term investment that compounds quietly but decisively over time. Leaders who get the most from it don’t see it as an intervention but as leverage in sensemaking. A way of working on themselves with the same rigor they bring to working on their organizations.

Further Reading