We don’t usually think of courage in the context of careers and organizations. But this is a mistake. Courage is more fundamental than we think, and equally relevant. The key is to understand the specific type of courage required, and how it applies to an ordinary work life.

Ordinary courage

What does courage mean in modern leadership? The notion of the swashbuckling leader is as cliched as it is anachronistic. Still, it persists. We think of Elon Musk as courageous for taking bold risks.

But what does it mean for lesser mortals like us, at various stages of careers and at different levels in the organization? What does it mean for a team lead or an individual contributor to be “courageous” in the daily grind of work?

The courage required in organizations is very different from common notions we typically carry. It’s also easy to avoid this form of courage. In many ways, this makes it harder than the kind that Musk demonstrates.

Understanding and recognizing it can be instrumental in avoiding common stumbling blocks in leadership, and careers as a whole.

Courage as foundational

In Mavericks [2], Lewis, Goddard, and Batcheller-Adams, identify five attributes of what they call the “Maverick leadership mindset”:

Belief: …The Maverick leader, in the face of what seem to be systemic, ineffective and unjust outcomes, resolves to take action to make things better. They assess options, seize opportunities and side-step barriers with an absence of ego, the need to be right or personal preference. Rather, they act informed by a vision of what better looks like.

Resourceful: …The Maverick leader, through curiosity, identifies opportunities to connect people, ideas and assets that to others may seem unconnected or too bothersome to engage in.

Nonconformist: …The Maverick leader challenges orthodoxy, not for the sake of being obstinate or contrary, but to break out of the box and create something better.

Experimental: … The Maverick leader recognizes that there is no proven path to a better future, yet is determined to take the first step, learn and work out, along the way, how to make progress while others simply give up.

Undeterred: …The Maverick leader persists in striving to make things better, in the face of difficulty, resistance and even outright hostility, through the force of their own will. In the face of setbacks and little or no indication of success, they find ways to stay energized and garner support when needed.

What’s interesting about these attributes is that courage is foundational to all of them. Without courage, acting consistently on these mindsets is near impossible.

Courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point.

—C.S. Lewis

Rollo May [3] recognized this foundational quality of courage:

The word courage comes from the same stem as the French word coeur, meaning “heart.” Thus just as one’s heart, by pumping blood to one’s arms, legs, and brain enables all the other physical organs to function, so courage makes possible all the psychological virtues.

…In human beings courage is necessary to make being and becoming possible. An assertion of the self, a commitment, is essential if the self is to have any reality. This is the distinction between human beings and the rest of nature.

The acorn becomes an oak by means of automatic growth; no commitment is necessary. The kitten similarly becomes a cat on the basis of instinct. Nature and being are identical in creatures like them. But a man or woman becomes fully human only by his or her choices and his or her commitment to them.

People attain worth and dignity by the multitude of decisions they make from day by day. These decisions require courage. This is why Paul Tillich speaks of courage as ontological—it is essential to our being.

May is alluding to a specific type of existential courage that’s more applicable to work and careers, and not as widely recognized.

Types of courage

Research suggests three primary types of courage:

- Physical courage (valor, military bravery)

- Moral courage (standing up for what’s right)

- Psychological courage (internal battles, existential)

Most of us recognize physical and moral bravery, and it’s what Hollywood typically portrays. However, in careers and organizations, it’s the third type that can make or break us.

Psychological courage often goes undetected and underdeveloped. One reason is because it’s easy to avoid it. In the moment, we typically have a choice to go for the more safer, comfortable option.

Sometimes called emotional courage, psychological courage is more existential in nature — our ability and willingness to face and cope with the inevitable uncomfortable emotions produced by important but avoidable actions.

One aspect particularly useful in identifying this type of courage, is the existentialist notion of courage as the ability to deal with anxiety. And leadership is an excellent use-case for its application.

Anxiety is in the nature of leadership

Why is courage foundational to leadership? One reason is because anxiety is an ever-present dynamic in leadership, and courage determines how we engage with it — facing it and growing in the process, or avoiding it and shrinking away.

What's the relationship between leadership, anxiety, and courage? Peter Koestenbaum [1] articulated it this way:

Anxiety is the experience of thought becoming action. What do you feel when reflection becomes behavior, when strategy becomes implementation? Anxiety is the feeling of leadership in action, of theory being transformed into practice.

This explains why ideas are cheap, while executing on ideas in the real world comes at a premium.

Courage, as a dominant strategy, or dimension, for acquiring the leadership mind, is the willingness to risk. … The courageous leadership mind understands that you cannot live life without courage. And the leader knows that courage does not avoid anxiety and guilt but uses them constructively. To lead is to act. … courage means to act with sustained initiative.

Courage is the free decision to tolerate maximum amounts of anxiety, to manage your anxiety constructively, to understand that being anxious is what it feels like to grow.

...The fact that anxiety is the natural condition of human beings rather than a pathological aberration is the pivot ….

...You should face your anxiety, you should stay with your anxiety, and you should explore your anxiety. The same is true of the decision to tolerate guilt.

In general, management techniques, useful as they may be, are often more escapes from courage than effective tools to harness courage.

What courage looks like in organizations

Now that we know the type of courage we need more of, what does it look like in common work scenarios? How does it play out in organizational leadership?

Courage can be as simple as facing up to what is, rather than bemoaning how things “should” be. Things simply are. The real question is what are we going to do about it? How do we close the gap between the desired future and today’s reality?

It requires the paradoxical combination of conviction and humility — the conviction that you can, in fact, improve/change it, and the humility to recognize the reality of the situation.

Here are some common organizational scenarios that require psychological courage, and a new way of seeing them.

1. Difficult conversations

Consider the last time you avoided a painful conversation, or didn’t challenge your VP’s position even when you knew a lot more than they did.

Doing so requires redefining our relationship with anxiety and uncertainty —recognizing them as part of the human condition, and not as signals that indicate if something is good or bad. Instead of trying to get rid of discomfort, it can be seen as an opportunity to grow that we run towards.

In real-world situations, the practical formula with respect to anxiety is this: go where the pain is.

…That is a technique for achieving leadership courage. Explore your moments of anxiety. Examine your nightmares. Do not fear them, and do not deny them.

— Peter Koestenbaum in Leadership [1]

2. Risking vulnerability

Genuine relationships and authentic leadership require an element of vulnerability. Human beings are attuned to picking this up. Of course, leaders are trained to do everything but show vulnerability. This means your willingness to risk being vulnerable is an act of courage in itself.

Vulnerability is the road towards courage. You cannot be courageous without being vulnerable. When we hear the word vulnerability, we often mistakenly confuse the term with fragile. However, vulnerability is a universally human feeling that occurs when we find ourselves in difficult situations that are characterized by uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.

– Morten Henriksen, Thomas Lundsby in Fearless Leadership

3. Creative originality as an antidote

It’s easy to get stifled in organizational setups. There are the processes, deliverables, metrics, structures — all designed to control, and supposedly manufacture “innovation”. But in practice, it’s the opposite — they kill creativity and drive.

Questioning these structures, and actively working to subvert them, can put life into an otherwise dull and mundane “organization man” existence. Of course, this comes with its attendant risk, which is precisely what makes it difficult and uncommon. Used intelligently, it can be a source of engagement and competitive advantage.

To live with courage in any work or in any organization, we must know intimately the part of us that does not give a damn about the organization or the work. That knows how to live outside the law as well as within it. …

With a healthy outlaw approach, we are outside the laws of predictable cause and effect and inside the intensity of creative originality.

— David Whyte in Crossing the Unknown Sea

4. Questioning accepted norms

How do “best practices” and the “status quo” become that way? They are the safer bet, and most don’t have the courage to question them. We forget that every formula and best practice was once an untried theory, or more likely, emerged from grappling and trying different things. Someone else’s formula rarely works for the specific complexities of our own situation.

[Maverick leaders] resist the popular notion that effective practice is essentially the application of proven knowledge or the adoption of best practice. In a sense, Mavericks reverse the standard model of the growth of knowledge by cleaving to the belief that most theory is the post-rationalization of the discoveries first made by those solving practical problems...

— from Mavericks [2]

5. Difficult decisions

An obvious anxiety producing aspect of modern leadership is decision-making. Critical choices often come coupled with lack of clarity and consequences for many. Not recognizing the role of anxiety and how it influences decisions can be a blindspot. Consider the following questions by Henriksen and Lundby [5]:

1. How do I experience difficult decisions?

2. How do I cope with doubt in decision-making processes?

3. How do I cope with my own insecurity in decision-making?

4. Are there areas in which I delay decisions because I fear the consequences?

5. How is my ability to take responsibility, despite my experience of considerable insecurity?

6. How is my ability to act independently? To how large an extent am I dependent on the attitudes, feelings and social norms of others?

Regularly asking these questions, when making decisions, builds the anxiety-embracing muscle.

6. Independent thinking

Intellectual tenacity requires the ability to think on your own, and to develop an independent viewpoint. Forging your own path is never convenient and comes with downside risk. The herd is usually right, and a contrarian view by definition means going against conventional wisdom.

Often independent thinking is simply a question of deciding to use it, rather than skill – the decision is to not fall for the easier choice of basing it on other people’s thinking.

Sapere aude!—Dare to reason! Have the courage to use your own minds!—is the motto of the enlightenment. . . . If I have a book which understands for me, a pastor who has a conscience for me, a doctor who decides my diet, I need not trouble myself. If I am willing to pay, I need not think. Others will do it for me.

— Immanuel Kant

7. Taking responsibility

Organizational life is often about deflecting blame, or passing responsibility onto others. Let’s face it — accepting mistakes or failures can easily derail careers. It’s a lot easier and safer to deflect. But this can also translate into not taking enough risk, and playing it too safe.

The possibility of surprises, or things not playing out per plan, are always there. Understanding that responsibility comes packaged with anxiety is useful, and can help to look at risk more objectively.

Responsibility is something we face and something we try to escape...There is something fearful about man’s responsibility...It is fearful to know at this moment we bear the responsibility for the next, and that every decision from the smallest to the largest is a decision for all eternity—that at every moment we bring to reality— or miss—a possibility that exists only for the particular moment.

...But it is glorious to know that the future, our own and therewith the future of people and things around us, is dependent—even if only to a tiny extent—upon our decision at any given moment.

— Viktor Frankl in The Doctor and The Soul

8. The courage to execute

As glamorous as strategy is, execution can be equally mundane. The requisite strategy is often well understood. What is less common is the courage to execute on those strategies, and stick with them long enough to get the desired results.

The single biggest barrier to implementing any strategy is courage. What makes our superstar managers so impressive is not what they are doing, but the fact that they are doing it. Many people (and firms) lack the guts to stick with the plans and goals they have set for themselves. They lack the courage of their own convictions….

— David Maister in Practice What Your Preach

Maister calls this “insistent patience”:

Just as management involves a delicate balance between being supportive and being demanding, it also requires a style of insistent patience. Patience that “Rome doesn’t get built in a day,” and insistence that “We are building Rome.”

… People must believe that the manager has the courage to believe in something and, more importantly, the guts to stick with it. There is no greater condemnation of a manager than to say that he or she is expedient, and no greater commendation than to say that he or she truly lives and acts in accordance with what he or she preaches.

9. Innovation

Innovation gets proudly featured in almost all “corporate speak”, but most organizations are designed to suppress it. True innovation requires open experimentation, the willingness to fail, and also knowing when to change, correct course, and even quit.

Courage underlies all these. It means remembering that risk can be mitigated, but uncertainty cannot be eliminated.

The challenge is to create a corporate culture that is comfortable trying things out, that possesses a kind of daring-do, that places greater emphasis on discovery than analysis, and that relies more upon iterative processes of exploration.

Instead of believing that the future can be plotted intellectually like a journey to a chosen destination, perhaps the art is to be more nomadic… Instead of more thinking, perhaps there should be more action; instead of diligence, greater daring; and instead of ‘why me?’, an attitude of ‘why not?’.

— from Mavericks [2]

10. Combating learned helplessness

Each small action and decision shapes our identity. Embrace inaction and resigned acceptance for too long, and we end up being an organizational sleepwalker — an also ran. Courage is a muscle that has to be exercised regularly, and that can easily atrophy due to lack of use.

It’s easy to fall into the disempowering notion that your actions on their own are not going to change things. But this can be especially telling if you lead in any capacity. Consider Robert F Kennedy’s iconic lines:

Few will have the greatness to bend history itself, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events. It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

— from Mavericks [2]

We might not be creating giant waves, but our actions nevertheless create “tiny ripples”. Regardless of how subtle they are, every action or a lack of action gets interpreted and copied through the organization. This is as true for division heads, as it is for project leads.

“Bending history” is the equivalent of bending “organizational norms” that go unquestioned, but are, in fact, the bane of everyone’s existence. One reason the status quo is resilient, is because everyone’s simply accepted that’s the way it is.

Developing the character of leadership

Why bother with all this? Why inflict unnecessary pain? It’s the only way to develop depth of character, one that can withstand the demands of modern leadership. It's also what makes for an interesting career, and life.

...Character is developed by going through the existential crisis, which means to allow anxiety to come to full flowering. Do not fear anxiety. Instead, allow yourself to feel it fully. You come out at the other end of the process strong and resilient, wise and mature.

… No significant decision, personal or corporate, professional or military, has been undertaken without its own existential crisis, the leader choosing to wade through rapids of anxiety, uncertainty, and guilt. It is such crises of the soul that give leaders their character and their potency.

— Peter Koestenbaum in Leadership

The construct of courage is an important one because it explains how many of us become jaded in careers over time. Often the convenient option is also the more dangerous one in the long run. And one mechanism that corrodes spirit is a continued lack of courage — conform to the norms too long, and soon the original drive is lost.

Not rocking the boat equals mediocrity

It's common to get habituated to staying within our comfort zone, especially at work.

The mantra becomes “don’t rock the boat” — but over time this turns our boat designed for sailing, into a rock sitting stagnant on the beach of possibilities.

This doesn’t happen in a momentous, clearly defined moment, but rather in hundreds of small decisions or inactions that we lull ourselves into over time.

Why does this happen? Because to do otherwise is plain inconvenient and potentially risky. Culture and organizations program us, even incentivize, to avoid this kind of risk.

But avoiding it also means mediocrity. When we find ourselves in the middle of a not-so-fulfilling career, it’s often because we are not challenged by an “existential risk”.

Mediocrity might guarantee “existence”, but often a dull one instead of one worth living for.

Related Reading

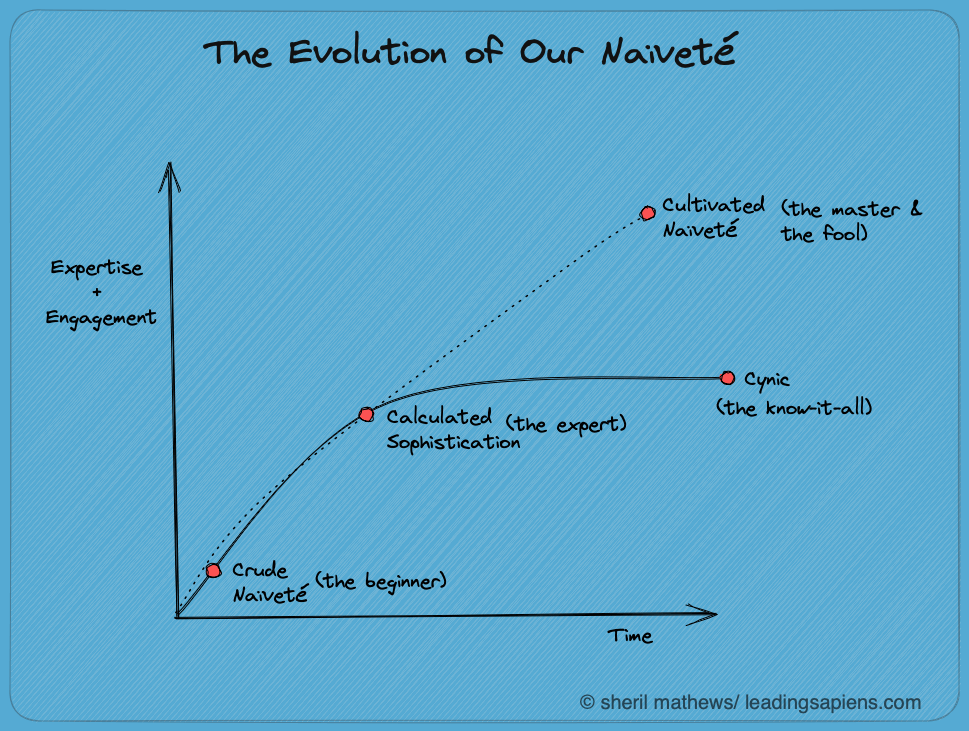

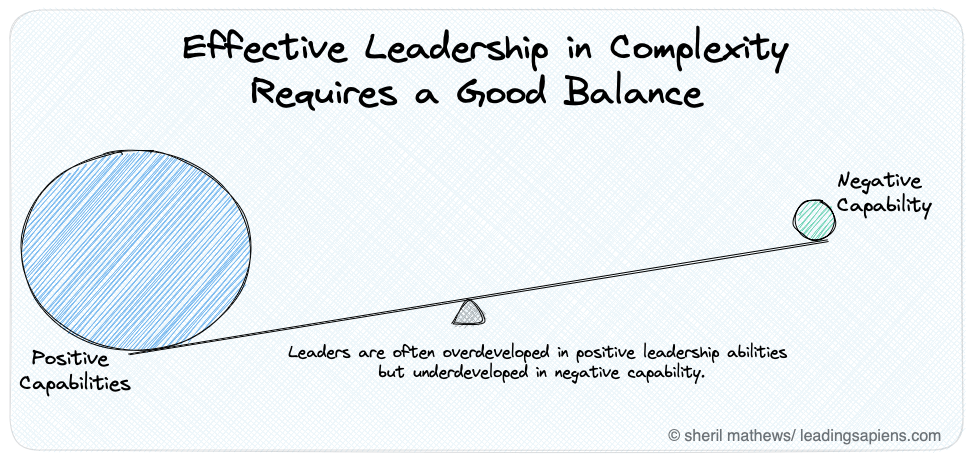

Another way of looking at courage in leadership and organizations is to understand the counter-intuitive notions of developing naiveté and negative capability in leadership:

Sources and references

- Leadership: Inner Side of Greatness by Peter Koestenbaum

- Mavericks by David Lewis, Jules Goddard, Tamryn Batcheller-Adams

- The Courage to Create by Rollo May

- Leading with Emotional Courage by Peter Bregman

- Fearless Leadership by Morten Henriksen, Thomas Lundby

- Practice What you Preach by David Maister

- Crossing the Unknown Sea by David Whyte