We think of capability as a positive term— it’s active and additive rather than passive and subtractive. In leadership, it’s about proactive action, getting things done, leading the way, and delivering on results and desired outcomes.

But this pre-occupation with action and results can also mean an inability to handle more complex, unknown situations where actions and outcomes might not be as clear. Ironically most leaders operate in conditions of complexity and uncertainty.

How do we go about correcting this imbalance? How can we better position ourselves to operate effectively in uncertain conditions? One place to start is to develop negative capability.

In this article we cover:

- What is negative capability?

- What defines negative capability?

- Why negative capability is critical in leadership

- How good is your negative capability?

- What prevents negative capability?

What is negative capability

The English poet John Keats coined the term in 1817 in a letter to his brother George:

At once it struck me what quality went to form a man of achievement especially in literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously— I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.

While Keats was trying to capture the thought process of literary geniuses, the concept is equally applicable to modern leadership. Leaders today operate in complex environments rife with ambiguity and uncertainty.

But the external expectations of being all-knowing works against operating efficiently in that kind of environment. What is needed is an openness to not-knowing and staying with the anxiety that it creates.

Negative capability has two paradoxical aspects:

- Of “being in”/“being with” : “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts” and

- Of “being without” : “without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”

Capability at first glance is a positive term. Keats combined it with negative thus capturing its paradox. It’s a capability that goes against human nature.

It refers both to a set of skills that involve ‘not-doing’, as opposed to doing - a negative kind of capability - as well as to the fact that this skill involves confronting negative (as in ‘unpleasant’) thoughts, emotions, and situations.

- Oliver Burkeman in The Antidote

What defines negative capability

Operating in uncertainty requires a different set of skills in contrast to known situations. Negative capability is a way of operating in conditions of uncertainty defined by an ability to stay with the discomfort and anxiety of doubt and not-knowing.

The uncertainty is akin to the negative space implied by the latin root of capability – capabilis, which means “able to hold” or “to contain” .

We can either rush in to fill it with what we already know, or let the empty space create something new. Do we rush in to resolve a situation with habitual activity, emotions, and thoughts, or do we stay with the discomfort long enough to yield different answers?

What are some distinguishing characteristics of negative capability and how is it different from “positive” leadership competencies?

1. A capacity to contain and tolerate anxiety and doubt

Standard responses to anxiety can be rationalization, denial, panic, and regression to more primitive, less adaptive behaviors.

In contrast, tolerating fear and staying in uncertainty allows for the emergence of new thoughts, perceptions, and solutions. Negative capability helps to function effectively in new environments where our mental models are non-existent or less developed.

This includes uncertainty not just in the external environment but internal demons as well. By changing our relationship with anxiety and doubt it enables not just surviving in uncertain conditions but also thriving in them as sources of creativity and innovation.

2. Courage as a different relationship with incertitude

The notion of bold leadership is almost a cliche. But bold can also mean a different relationship with a volatile, uncertain world. It means staying with the discomfort and continuing to play even when you don’t know where exactly it will lead, or what the correct solution looks like.

Courage means resisting the pressure to resolve what might be unresolvable and the ability to recognize it as such. It’s an active but non-defensive stance towards change — a surrender of control and knowing by accepting things as they are, but also coupled with the willingness to engage and respond.

3. Wisdom as not-knowing

In a knowledge work economy not-knowing can be anathema. As a culture we are allergic to the notion of not-knowing especially in leadership. But novel situations by definition mean we do not know. Do we then embrace it and work with it or fall back to known but unhelpful patterns?

Negative capability requires a proactive acceptance that there will be in situations where we don't know the answers. Situations where we have only partial information or even unknowable.

Instead of getting flustered and anxious, staying with it and even reveling in it increases engagement which paradoxically increases the likelihood of finding answers.

4. Cultivating proactive, deliberate openness

Negative capability requires staying actively openminded by resisting the habit of “reaching for” explanations or quick answers. This requires large amounts of tolerance for ambiguity and patience.

Below are some practices:

- Embracing leaving issues unresolved as receptive inaction.[2]

- Resisting rushing into and actively delaying interpretations of someone’s behavior or a situation.

- Staying open to nuances instead of falling victim to premature hubris and confidence.

- Allowing room for new inputs and learning.

- Allowing ourselves to be changed by others.

- Being imaginative while avoiding the urge for closure.

5. Doubt as a positive

Doubt is not a pleasant mental state but certainty is a ridiculous one.

- Voltaire

Negative capability gives doubt a positive role in leadership. When we are absolutely sure of something, it also means other possibilities are ruled out. But doubt, rather than being an impediment to decision making, also means openness to other explanations.

Negative capability is a healthier version of doubt — a proactive refusal and push against final conclusions to leave room for alternate approaches and explanations.

6. Paying attention to non-attention

Negative capability is about what our attention is on and by extension what it’s not on- is it on the obvious in your face issues, or are we paying attention to nuances between the lines and the overall context of a given situation?

7. Efficient is not necessarily effective

In situations of uncertainty, it’s efficient to jump to pre-mature conclusions or interpret it based on past experience and assuming we understand. But in novel complex scenarios, it pays to stay with the discomfort long enough in order to unearth as many different perspectives as possible. Do we let open-ended situations naturally evolve or do we move to close them prematurely?

Why negative capability is critical in leadership

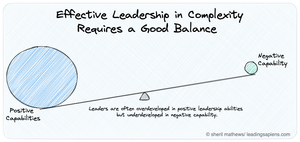

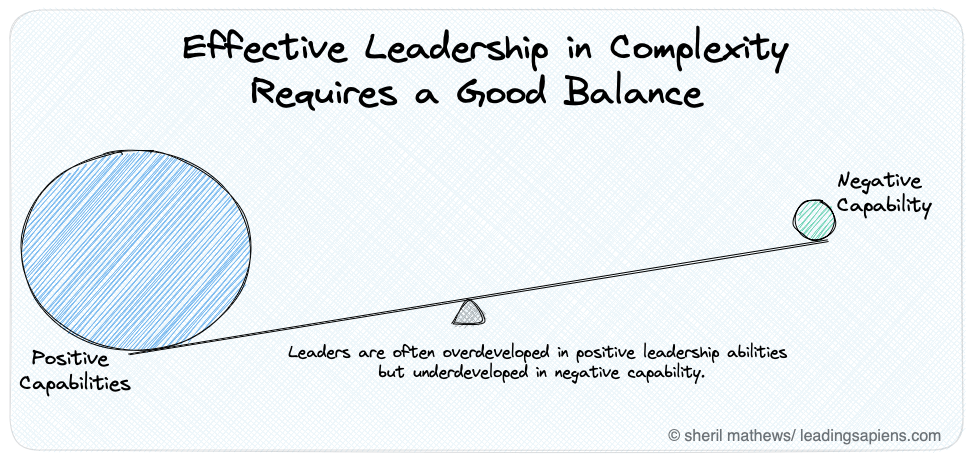

Negative capability is especially relevant for leaders and managers as a group and almost a requirement for operating effectively. But leadership development by default tends to be positive and additive – the skills and competencies purported to make you a better leader that you layer one on top of the other.

The capacity of a vessel is determined more by its negative space and less by the amount of “positive” material added. At the same time, one cannot exist without the other.

An exclusive focus on “positive” leadership competencies is only one side of the coin. Equally important is to develop negative capability to handle situations when pre-learned competencies are not enough.

1. Responding appropriately

In disaster literature there is a critical time period – a window of opportunity during which actions either avert the disaster or accelerate conditions leading to it. The sense-making and decision-making during this time window determines outcomes and even lives. Two classic examples are the actions of the Apollo 13 crew vs that of the 3 Mile Island nuclear disaster with very different outcomes.

While most leaders will not have to deal with such extreme conditions, almost every critical decision they make straddles this spectrum between denial and panic. One has a lack of actions while the other has too many. Both responses are misaligned with what the situation requires.

Whether they respond appropriately or lean towards either extremes depends on their negative capability.

2. Bucking the norm of organizational absurdity

In organizations, certainty is valued while uncertainty is treated as an anomaly to be stamped out. Leaders are expected to not show doubt. Many put up a facade of certainty even when conditions are otherwise. There is no room for “not-knowing” which is often misconstrued as ignorance due to the binary, dichotomous thinking that pervades organizations.

It’s either a success or a failure. You either know or you are ignorant. There is no middle ground of temporary “not knowing”. We are always “reaching for” understanding and figuring it all out.

Negative capability recognizes that there are paradoxes that cannot be solved away. But being aware makes it possible to pay attention to them and thus respond appropriately. It’s the difference between a reactive stance vs a responsive one.

The constraints, norms, unspoken rules, and other mechanisms of organizational life often go unquestioned and can be difficult to stand up against even when they are unhelpful and borderline stupid. Negative capability helps build a backbone and take a contrarian stance when needed.

3. The myth of speed in decision making

Acting decisively is prized in organizations and necessarily so. But quickness is often coupled with decisiveness. Slowing down is viewed in a negative light as indecision. This leads to the mistaken notion of speed as a positive in decision making.

In his study of successful companies Jim Collins found this notion of speed one-sided and misleading:

Sometimes acting too fast increases risk. Sometimes acting too slow increases risk. The critical question is, “How much time before your risk profile changes?” Do you have seconds? Minutes? Hours? Days? Weeks? Months? Years? Decades?

The primary difficulty lies not in answering the question but in having the presence of mind to ask the question.

The 10X teams tended to take their time, to let events unfold, when the risk profile was changing slowly; yet equally, they prepared to act blindingly fast in the event that the risk profile began to change rapidly.

One of the most dangerous false beliefs is that faster is always better, that the fast always beat the slow, that you are either the quick or the dead. Sometimes the quick are the dead.

- Jim Collins in Great by Choice

Whether leaders stop to ask this critical question or fall prey to the wrongheaded notion of quick decision-making depends on their negative capability. Do they respond to what the situation actually requires or do they fall prey to expectations removed from the context of the situation?

4. Enduring uncertainty vs enjoying it

Leaders are often in entangled situations without clear solutions or even a clearly defined problem. What is needed is a capacity to grapple with reality but doing it with a sense of discovery and curiosity instead of something to get rid of.

One of the hallmarks of modern leadership is the omnipresence of uncertainty and ambiguity. Which begs the question : would you rather endure it or enjoy it?

Enduring something implies it will come to an end at some point. Except uncertainty is not going anywhere. This makes the case for reveling in uncertainty rather than enduring it.

The sense of discomfort, insecurity, and not knowing causes us to revert to more primitive, less practiced behaviors. The ability to stay with the situation long enough comes from a well developed negative capability.

5. Negative capability is a differentiator

It makes top performers stand out from the crowd. At the highest levels everyone is already pretty good at positive capabilities — producing results and getting things done.

But are they equally good at negative capability? Can they operate in environments of ambiguity, low definition, and lack of information?

6. Developing leadership presence

Leadership presence can be a misleading topic leading to an unnecessary preoccupation with how we are coming across to others. Often it ends up with the exact opposite of presence. Negative capability can be an effective way to access this elusive quality of leadership.

Being present to what’s transpiring in the moment starts by being comfortable with the discomfort of not knowing .

Paying undivided attention to what’s unfolding, and suspending preexisting notions and interpretations to clear space for a fresh take on what’s in front of us, naturally develops presence.

7. Negative capability develops empathy

Negative capability also helps engender the often vague notion of empathy. It has a dimension of acceptance that also means accepting people in their many facets which is required for developing empathy, trust, and respect.

Without openness and acceptance, there is little chance of developing empathy beyond lip service. But it takes work and is not comfortable. It’s a lot easier to box people into categories and respond accordingly.

Negative capability opens up the space for leaders to become more attuned to people and situations.

8. Preventing leadership derailment

One of the recurring themes of executive derailment studies is the failure to adapt to not just changing external conditions but also what the role requires. Thus what might have been a strength before in a previous role quickly turns into a liability in a new setting.

As McCall, Morgan, and Lombardo (1983) discovered in their findings on successful and unsuccessful business leaders, ‘the most frequent cause for derailment (along the path to the executive suite) was insensitivity to other people’.

- Manfred Kets De Vries in The Hedgehog Effect

Negative capability helps buck this trend by its focus on responding anew to each moment instead of operating from what we already know and existing mental models.

9. Battling heroic leadership

The expectations of certainty and heroic leadership places unnecessary burden on modern day leaders. Negative capability acts as a check and bulwark against these misguided notions.

It helps guard against unrealistic expectations from leaders like needing to know everything or quick decision making.

10. Leadership as a creative act

Are paradoxes and complexity seen as constrictive or generative? Underlying assumptions determine how leaders perceive organizations and situations:

- Messy vs Polished

- Evolving vs Already formed

- Everything should be known vs we are still finding out

- We should know everything vs we are still learning

Leadership is a creative act — a step into the unknown and helping others do the same. Ambiguity, uncertainty, change, and frustration are a part and parcel of the creative process. Negative capability helps leaders harness these ever present conditions.

Its focus on engaging with reality can help attain the psychological condition of flow which is associated with high levels of creativity. Flow requires losing the “you” in the process. “Reaching for facts and reason” prevents flow and thus creative breakthroughs as well.

11. Building resilience

Reality in its full glory can be painful to grapple with. Somehow our culture conspires to convince us as otherwise. Negative capability helps recognize this and contain the emotional turmoil of opening up to the full realities of a given situation.

How good is your negative capability

Consider your instinctive responses to the following questions. Your answers will indicate how well developed your negative capability is.

- Do you detest operating in environments with lack of definition, too many open loops, lack of information, and ambiguity? Or do you revel in them?

- Do you see ambiguity as an anomaly or as a nature of the system, as something to be eliminated or as “conditions of the game”?

- Do you actively suspend judgment or do you rush to conclusions? Often rushing to conclusions masquerades as competency in a given domain.

- When encountering puzzling situations what’s your first reaction? Do you dismiss them or do you impose certainty prematurely by leaning on previous knowledge?

- What is your default attitude towards uncertainty? Do you detest it, endure it, or enjoy it?

- Can you continue operating without certainty or do you hurry to resolve the situation?

- What’s your attitude towards anxiety? Is it an anomaly and a negative signal?

- Do you get over-anxious in unknown, unexplainable situations?

- Do you stay with the discomfort or do you actively work to eliminate it?

- When coming across new ideas that challenge your existing position, are you naturally closed or open to them? Do you stay open to the possibility of changing your mind?

- How developed are your imaginative skills without needing a lot of specificity?

What prevents negative capability?

Why are we naturally wired to resist negative capability? Why do few people have it naturally while the rest of us have to proactively work at it? And why is it especially hard to do in leadership?

1. Anxiety is treated as an anomaly

The primary mechanism that works against developing negative capability is what Jacob Needleman fittingly calls “dispersal”.

Uncertainty causes anxiety, and anxiety is a form of creative energy. But too often in a world seeking perfection we treat anxiety as a negative signal and disperse it away instead of harnessing its creative force. The primary ways we do this are : “explanations, emotional reactions, or physical action”.

There is a tension between our desire to grapple with reality and the anxiety associated with a fear of the unknown.

What are the typical ways we disperse energy?

- Shutting out new ideas or new feelings that make us anxious or fearful.

- Instead of staying with situations and letting them ripen, we speed things up and resolve them prematurely. We make them things linear, or choices as binary where they might not be.

- Listening to only what we want to hear and dismissing any contradictory information.

- Relying on previous knowledge which might not be applicable anymore.

- Rushing in to take action because waiting is too painful or because that’s what we are expected to do.

- Imposing a new certainty on evolving situations before a new pattern has emerged.

- Oversimplifying complex problems into simpler ones by ignoring relevant primary issues.

- Resisting any kind of “reflective inaction” or pausing by using lack of time as an excuse.

- Treating patience, listening, and waiting as liabilities and signs of indecision and weakness.

2. Existing habit patterns and notions

Over a lifetime of interactions we develop habit patterns of responding to situations and people. Often we are not even responding to what’s in front of us but instead to pre-existing patterns.

One illustration:

A man wants to hang a picture. He has a nail, but no hammer. The neighbor has one so our man decides to borrow it. But then a doubt occurs to him.

“What if the neighbor won’t let me have it? Yesterday he barely nodded when I greeted him. Perhaps he was in a hurry. But perhaps he pretended to be in a hurry because he does not like me. And why would he not like me? I have always been nice to him; he obviously imagines something. If someone wanted to borrow one of my tools, I would of course give it to him. So why doesn’t he want to lend me his hammer? How can one refuse such a simple request? People like him really poison one’s life. He probably even imagines that I depend on him just because he has a hammer. I’ll give him a piece of my mind.”

And so our man storms over to the neighbor’s apartment and rings the bell. The neighbor opens the door, but before he can even say “Good morning,” our man shouts. “And you can keep your damned hammer, you oaf!”

- Paul Watzlawick in The Situation Is Hopeless but Not Serious: The Pursuit of Unhappiness

While clearly an exaggeration, we go through milder and sometimes more serious versions of this. Often we are not speaking with the person present but rather to their caricature we've built in our minds. We keep going back to habitual patterns because they are comfortable. They serve the evolutionary purpose of relieving anxiety and discomfort.

Negative capability requires suspending judgment and engaging with situations anew. This means staying alert to habitual patterns and bypassing them as needed.

3. Dynamics specific to leadership

In addition to the above two main mechanisms, there are nuances specific to leadership that make negative capability harder to learn.

- Being seen as all knowing and all controlling. Many leaders have the mistaken notion that you should always portray strength and an image of being all knowing and in control. Negative capability is often in direct conflict with this notion and thus hard to embrace.

- Reaching for certainty. Leadership is often equated with confidence and certitude. We are “irritably reaching” for a fact or model to get us the always elusive certainty that we crave.

- Limiting expectations of the norm. Leaders are expected to know, not-knowing is not an option. Teams might not be familiar with a leader who accepts they don’t know all the answers. This can increase their own anxiety and the leader needs to prepare them for it. Without mutual understanding this can look like ineffective leadership.

- Misunderstood as passiveness or submissive. In a culture that values results and outcomes above everything else, any behavior that tends to delay action gets misunderstood as being passive. This is unfortunate and leaders have to actively manage this perception and dynamic.

- Lack of conviction and courage. Embracing negative capability and developing it does not come naturally. Without the internal conviction and courage to follow through on it, it’s hard to stay with a program of developing it proactively.

- Commitment to development and change. In addition to conviction and courage, commitment is key. You have to see its benefits and that its well worth the effort, or you won’t have the patience and the will to deal with the pain of uncertainty and not knowing.

- Misunderstood as lacking purpose. While a stated purpose is good, it can also be emergent and evolving in the context of negative capability. This can easily get misconstrued as lacking a clear purpose or even clarity.

Thus as beneficial as negative capability can be to effective leadership, it is equally hard to implement in practice.

Conclusion

The true journey of discovery does not consist of searching for new landscapes, but in having ‘new eyes’.

- Marcel Proust

Proust was talking about our existing mental models of the world, and the only way to find or learn new ones is to temporarily suspend judgment, action, decision, and whatever our immediate impulse is to do. In some situations instead of “Don’t just stand there, do something”, it should be “Don’t just do something, stand there”.

Staying alert to our habitual patterns, noticing what triggers them, and working proactively to install new patterns as replacements is one way to start developing negative capability.

Keats’s epitaph on his gravestone does not bear his name. Instead it reads:

Here lies one whose name was writ in water.

Organizational life and leadership are similar in fluidity, change, and sometimes even absurdly flippant. Instead of rushing to figure out the latest trend or learn a new technique, a more effective way to prepare for complexity and ambiguity is to develop negative capability.

In closing, here’s another insightful piece from Keats that captures the paradox of how reaching for something makes it ever more elusive.

Dilke was a man who cannot feel he has a personal identity unless he has made up his mind about everything. The only means of strengthening one’s intellect is to make up one’s mind about nothing—to let the mind be a thoroughfare for all thoughts, not a select party.

The genus is not scarce in population; all the stubborn arguers you meet with are of the same brood — They never begin upon a subject they have not pre-resolved on… Dilke will never come at a truth as long as he lives, because he is always trying at it.

Further Reading

Paradoxes and contradictions are an inescapable part of organizational life and leadership. Recognizing them beforehand gives us a much better chance of responding effectively. I capture some of these paradoxes and contradictions in Inherent Paradoxes in Management and Types of Contradictions in Organizations.

Mastering context is a core leadership skill but does not get as much attention. Developing negative capability is almost a requirement if you are to master it. I do a deep dive into context in The Importance of Mastering Context in Effective Leadership.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_capability

- Keats and Negative Capability by Li Ou.

- Negative Capability in Leadership Practice by Charlotte von Bulow and Peter Simpson.

- Strategy without Design by Robert Chia, Robin Holt.

- The Antidote by Oliver Burkeman.

- The Hedgehog Effect by Manfred Kets de Vries.

- Great by Choice by Jim Collins.

- Tools and Techniques of Leadership and Management by Ralph Stacey.

- Negative capability:managing the confusing uncertainties of change by Robert French.

- Action learning, performativity and negative capability by John Edmonstone.

- Negative Capability and the Capacity to Think in the Present Moment: Some Implications for Leadership Practice by Peter Simpson and Robert French.

- Leadership and negative capability by Peter Simpson, Robert French and Charles E. Harvey.

- Reflections on Leadership and Career Development by Manfred Kets de Vries.

- Geeks & Geezers by Warren Bennis and Robert Thomas.

- Reconsidering Language Use in Our Talk of Expertise—Are We Missing Something? by John Shotter.

- The critical period of disasters: Insights from sense-making and psychoanalytic theory by Mark Stein.

- The Situation Is Hopeless but Not Serious: The Pursuit of Unhappiness by Paul Watzlawick