Decisions are heavily influenced by our existing mental models of the world. What makes it tricky is that most of these are hidden. We are looking at the world through colored glasses without realizing it all along.

One way to uncover these hidden mental models is using Chris Argyris' Ladder of Inference. It's a powerful tool to increase the quality of our decision making.

In this article we'll cover:

- What is The Ladder of Inference

- Steps on the ladder of inference

- Two recursive loops in the ladder

- How the ladder of inference helps with decisions

- How leaders can use the ladder of inference

- Reflective questions for better decisions based on the ladder of inference

- Video explaining the ladder of inference

What is The Ladder of Inference

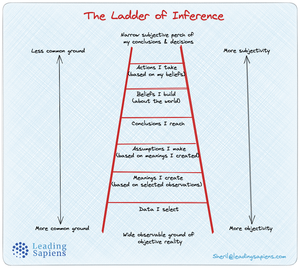

Developed by Harvard professor Chris Argyris, an organizational learning theorist and practitioner, it's a model that shows the stages we go through in making meaning of our experience, reaching conclusions, and taking action.

The stages of our thinking process are visualized as increasing steps on a ladder. It's a continuum that starts on the ground of objective and observable reality, and increases in abstraction and personal dimensions as we go higher up on the ladder. At the top, it ends with actions resulting from our conclusions.

The ground is where neutral, objective reality lies whereas the higher rungs on the ladder are where our particular versions of reality full of meanings, assumptions and inferences lie.

It shows how through a process of simplification, we create simplified internal maps of an otherwise complex external reality.

Steps on the ladder of inference

Step 0: The ground of reality

This is where we find testable, verifiable data. Something that a camera can record and play back. It could be an email, a meeting, a report, a spreadsheet, what someone said or someone’s body language. But it is objective, neutral and verifiable. This is what we might call reality as it happened. It is separate from our experience, our version of reality.

Steps 1 through 5 is where I create my personal version of reality.

Step 1: I select data

This is where simplification starts and the beginning of the simple logical story that is built from the chaos of reality.

Given the complexity of reality our brains cannot pay attention to every bit of information that comes in through our senses. We pick and choose the information that stands out for us ignoring the rest. What we pick is based on a set of pre-existing filters or mental models that we have developed over time.

These filters can include:

- Previous beliefs and inferences from previous journeys up the ladder.

- State of mind at that point in time.

- Previous experiences. Our history.

- The language and vocabulary we have for the given situation.

- Our cultural biases and notions.

- Any relevant training we have had.

Step 2 : I add meanings

From the data I select, I create personal meaning out of it even where there might not be any. We start fitting the selected data into a cogent story that makes sense to us.

Step 3: I make assumptions

Because reality by itself is neutral and does not have any meaning, we have to add assumptions in order to make sense of the meaning we are attaching to the story. This is where I am attaching my own interpretation and creating my personalized version of the story.

Step 4: I draw conclusions

Based on the meanings and assumptions, I come to conclusions. Conclusions tend to be more abstract and less open to interpretation. They are narrower in scope and easier to hold onto. They make sense to us. A logical extension of how it looks to us.

Step 5: I adopt beliefs

Cobble together enough conclusions over time and we create beliefs that are hard to change. And the conclusions and beliefs form the basis of the action that I take.

This is where the story is fully formed and leads me to take action.

Step 6: I take action

This is the concluding step of the ladder where I take action based on my beliefs and conclusions. [4]

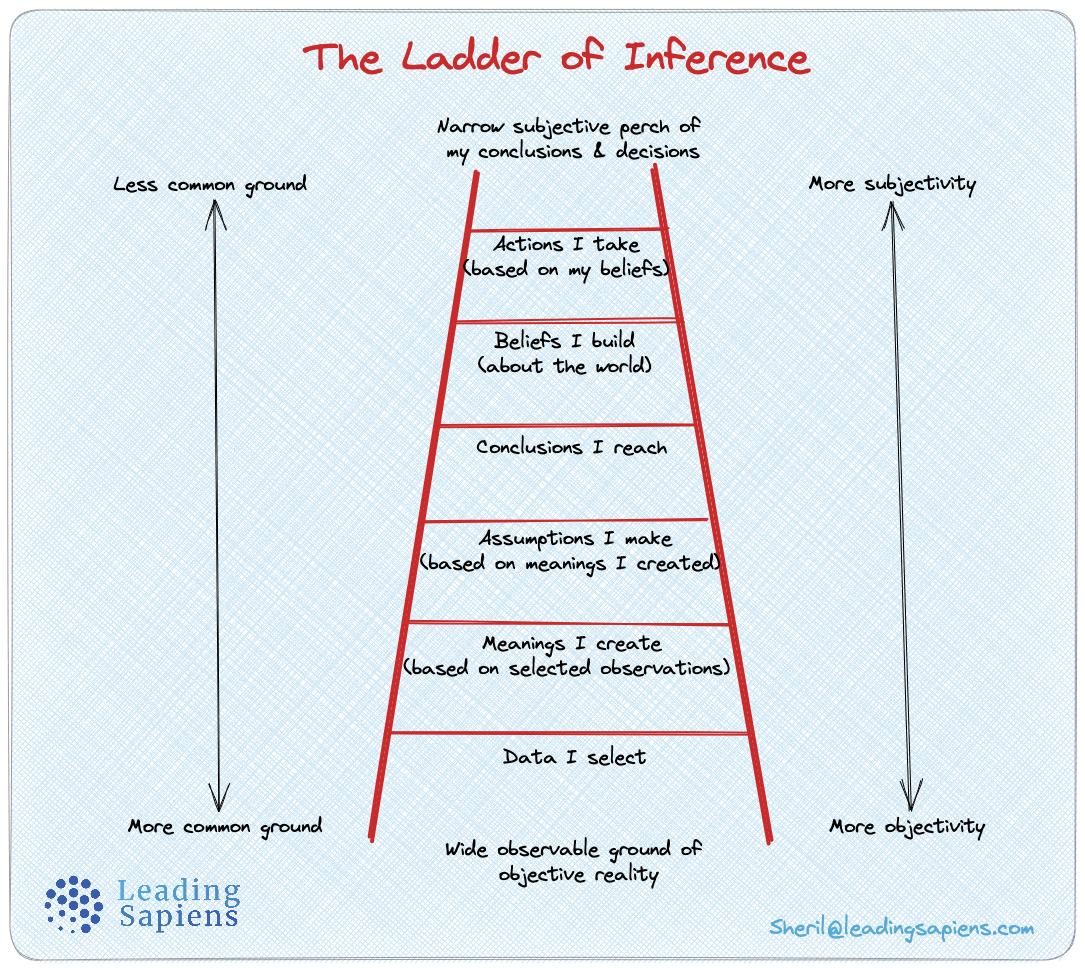

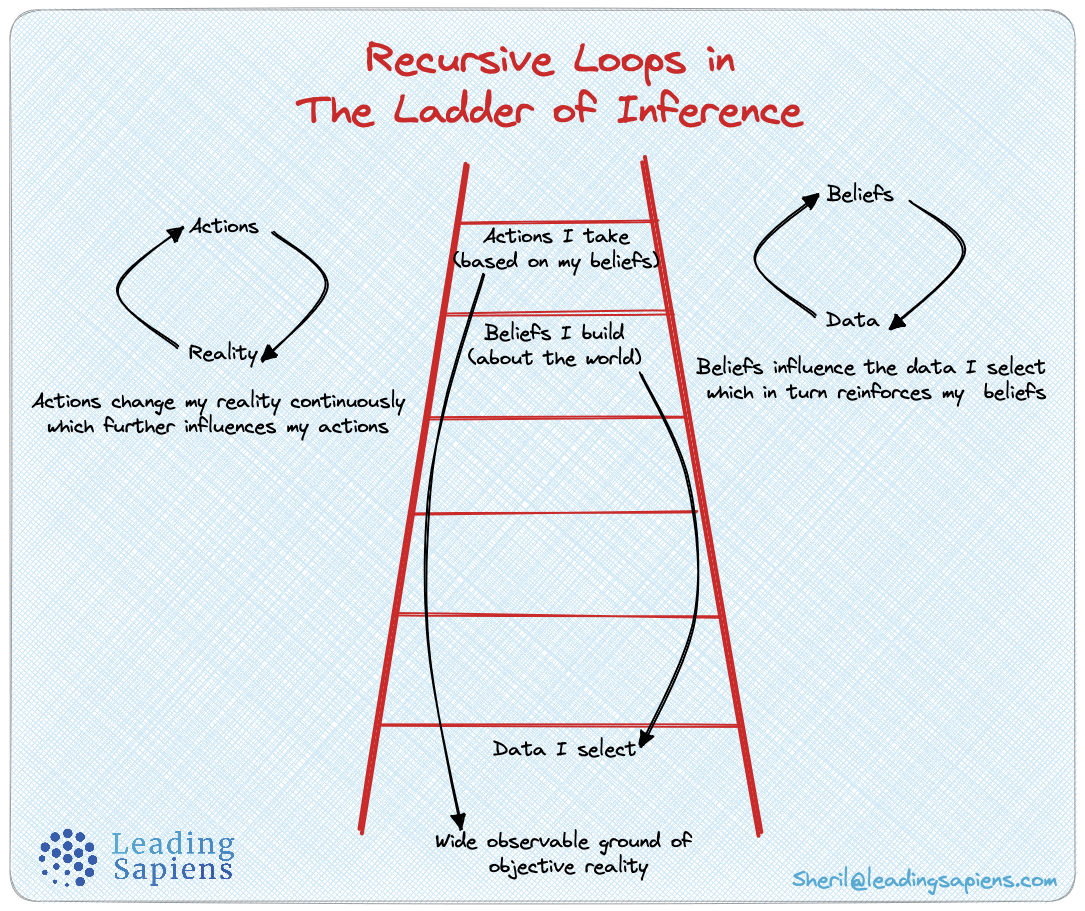

Two recursive loops in the ladder

First recursive loop is between my beliefs and the data I select.

My inferences and beliefs make me look for information to confirm them and ignore any disconfirming data. This in turn reinforces my beliefs. This is also known as confirmation bias and why it's so hard to change our beliefs. Left unexamined this is how we can have two opposing well-entrenched views that do not recognize each other’s “reality”.

The second recursive loop is between our actions and data from the resulting emerging reality.

Our actions change the very data we are working with. Different actions create different data and vice versa. For eg our actions influence the ladder of inference of the other person thus reinforcing their own recursive loops and their conclusions about us.

Argyris and Schon's framework of double-loop learning goes further into the mechanics of these loops.

How to use the ladder of inference for better decisions

One critical failing of our existing decision-making processes is that they tend to be conclusion oriented. We argue for the right answer, but we have little incentive to question why or how we believe in it, nor to question our inferences and note gaps in our logic.

A superior decision-making process would require that we make our data and reasoning more explicit, to us and to others.

It would challenge us to understand the following:

How did we reach this conclusion? What data did we select? How did we make sense of it? And where did we make a big leap from concrete data to abstract inference? And how might we make our logic clearer and our conclusions richer?

-Roger Martin in Creating Great Choices [1]

Reflection is an indispensable part of the learning cycle and decision making. Experience on its own is not enough. Reflection is what turns experience into learning and wisdom.

Part of developing a reflective mindset is to train our minds to be more aware of our reasoning process. Just like a muscle that has not been used, most of us are not trained to use our reflective mindset. By creating awareness of our process of reaching conclusions we can start training this muscle.

📚 HBR 100 Best Reads: You also get a curated spreadsheet of the best articles Harvard Business Review has ever published. Spans 70 years, comes complete with categories and short summaries.

1. Slowing down the process of decision making

One way to train this muscle is to deliberately slow down the process of how we reach conclusions and decisions.

Deliberate practice slows the automatizing process. […]

Some music academies teach pianists to practice their pieces so slowly that if you can recognize the tune you’re playing too fast. Some golf academies slow down their pupils so it takes ninety seconds to finish a single swing.

- David Brooks in Second Mountain [2]

Going through the steps of the ladder of inference forces us to slow down and break up the thought process that happens inside our heads in a matter of milliseconds. What might have been obvious before turns out to have several layers of assumptions.

2. Developing awareness of action

The model gives us a way to reflect on action; the action of our thinking. A process that's although invisible but nevertheless plays an important role in our decision making and behavior.

The change comes naturally if we observe it non-judgmentally. As William Issacs puts it, “The key is to simply become aware of this, to make conscious just what we are doing. Awareness is curative.” [3]

By giving more granularity to how we process information and our resulting actions, it forces us to take a closer look at not just the what of our conclusions but also the how.

By going “up and down” on the ladder, leaders can understand how they reach conclusions and bring rigor to their thinking process. It helps develop skilled reflection as opposed to just plain rumination. It gives a methodology to trace back the steps in how we reached a certain conclusions and potentially open up new perspective and views that we might have missed.

It highlights how the ideas we think of as immutable facts, are in fact interpretations that we generate and thus more malleable.

It’s a powerful tool to track the internal processes of our thinking. This awareness helps us become more critical thinkers and in increasing the complexity of our thinking process.

It is impossible to begin to learn that which one thinks one already knows.

—Epictetus

3. The ladder shows how stories are collapsed versions of reality

First there is our experience. Then there is the meanings and inferences we make about this experience. Most of the time we do not notice the difference.

Humans are meaning making machines. We collapse and simplify our experience into stories and narratives that make logical sense. We cannot pay attention to every detail of reality coming in through our senses.

Simplification is how our brain operates efficiently without using up precious resources. All of us have our own personal collection of heuristics and mental models we have developed over time.

The ladder of inference breaks down this process of how we go about building these stories and models. We are constructing our own reality all the time. And because the process is fast and so close to us, we don’t realize it.

How leaders can use the ladder of inference

1. Your position on the ladder

Higher up I am on the ladder, more removed I am from reality and more likely that it is laden with assumptions.

Each rung of the ladder is more abstract than the one before it and further removed from objective observable reality. It's also more private and less examined as one moves further up.

Higher up on the ladder is also where most disagreements lie. The likelihood of different interpretations increases as one rises up the ladder. Lower down on the ladder is where we are likely to find mutual ground.

One way to break an impasse is to move everyone further down the ladder.

There is limited room to maneuver both literally and figuratively at the top of the ladder. Whereas at the bottom there is more room and common ground which is easier to agree and build upon.

2. Private versions of reality

Notice how ground zero has nothing to do with me but everything on the ladder is unique to me. Thus I am creating my own version of reality.

This also explains why two persons or teams can have entirely different experiences and come to very different conclusions from the same set of “data”. Each of us is living in our own private version of reality. These can be the same or the opposite of that of others.

“We never have sex,” Alvie Singer complains.

“We’re constantly having sex,” says his girlfriend.

“How often do you have sex?” asks their therapist.

“Three times a week!” they reply in unison.

- From the movie Annie Hall, cited in Difficult Conversations [7]

3. A framework for building relationships

Understanding another persons’s unique point of view is half the game in influencing others.

Humans have an innate need to be seen and heard, and the model gives an actionable framework to do just that. Often time we do not really know what the act of seeing and hearing actually means in practice.

By asking questions at various points on the ladder, leaders can build their own understanding and in the process build their relationship and credibility with others.

4. The role of language

Language plays a key role in all the steps. From the chaos of reality we are more likely to notice and pick things that we already have a language for. What I do not have a language for, I am not likely or unable to pick out.

Lower up on the ladder is where we have the most opportunity for improvement and influencing change. One way to change what data we focus on, is to change our framing of the problem itself using language.

The frame forces us to look for certain parts of the data rather than others. There is less opportunity to do so the further along we are in the process.

5. Speed of travel

Most of the process is invisible to us and others. Only the extremes are visible: the facts of what actually happened, and my conclusions or the actions that I took based on my conclusions. And because they are invisible, most of it goes unexamined.

The more experienced we are in a particular area in life, the more likely we are to travel faster on the ladder and thus jump to conclusions quickly without checking how we got there. This closes us off to new viewpoints or experiences.

What might look as efficient might actually be imprudent and not as efficient in the long run.

6. Accuracy is painful

In order to build an accurate map of reality I have to proactively seek disconfirming evidence and viewpoints. This creates both discomfort and insecurity.

Accurate map building is a painful process, jumping to conclusions is not.

Unless one has considered alternatives, one has a closed mind.

This, above all, explains why effective decision-makers deliberately disregard the second major command of the textbooks on decision-making and create dissension and disagreement, rather than consensus.

Decisions of the kind the executive has to make are not made well by acclamation. They are made well only if based on the clash of conflicting views, the dialogue between different points of view, the choice between different judgments.

The first rule in decision-making is that one does not make a decision unless there is disagreement.

-Peter Drucker, The Effective Executive [8]

7. Discerning between inferences vs facts

The trouble is not that we come to conclusions or draw inferences. This is an inevitable part of being human.

The trouble starts when our inferences and conclusions become incontrovertible, uncontested facts. When we cannot see the process of how we arrived at our conclusion, the whole ladder collapses into one solid fact. We end up having no differentiation between reality and our interpretation of it.

Everyone driving slower than you is an idiot and everyone driving faster than you is a maniac.

- George Carlin

Pay attention to where on the ladder you are in a discussion. If you are constantly staying on top of the ladder, it might be an unwillingness to understand or fear of opposing viewpoints. We are trying to protect ourselves and our viewpoints.

It might indicate an unwillingness to learn and not being willing to subject our reasoning to scrutiny and inquiry. We have to be better at balancing advocacy with inquiry.

8. Being decisive as a weakness

Decisiveness and resoluteness is valued in our culture to the point where anything against the contrary is perceived as weakness. But decisiveness can also mean traveling fast up on the ladder without checking assumptions. Resoluteness can also mean not looking at disconfirming information.

In evolving situations that are ambiguous and complex, this behavior can backfire. Leaders need to be able to take an objective look at their decision making process.

The two biggest barriers to good decision making are your ego and your blind spots.

Together, they make it difficult for you to objectively see what is true about you and your circumstances and to make the best possible decisions by getting the most out of others.

If you can understand how the machine that is the human brain works, you can understand why these barriers exist and how to adjust your behavior to make yourself happier, more effective, and better at interacting with others.

- Ray Dalio in Principles [5]

Reflective questions for better decisions based on the ladder of inference

Often in the fast paced world of managers and executives we operate on autopilot and do not have to check our assumptions at every step. Neither is this practical.

However, more often than not, managers will find themselves in crisis situations or situations that are complex and ambiguous with no clear answers, and where resolution will require leveraging the minds of several others. This is where reflection plays a key role.

Critical thinking can make or break the situation. As Henry Mintzberg puts it, reflection can act as the antidote to the typical paradoxes of managerial life:

It has been said of great athletes such as a Wayne Gretzky in hockey that they see the game just a bit slower than the other players, and so they are able to make that last-second maneuver.

Perhaps this is also characteristic of effective managers: faced with great pressure, they can cool it, sometimes just for a moment, in order to act thoughtfully.

-Henry Mintzberg in Managing [6]

But slowing down on its own might not yield us the answers. What is needed is a mind trained for skilled reflection.

Below are some critical questions designed to slow down the thinking process based on the ladder of inference. Managers and leaders should ask themselves these questions especially in a crisis, and in complex, ambiguous situations.

- What aspect of testable reality leads me to my current conclusion?

- What conclusion or explanation is closer to testable data?

- Am I further down or further up on the ladder of inference?

- How can I go further down the ladder?

- Is there a more generous interpretation I might not have considered?

- Can I make a lower level conclusion until I find more about this issue?

- How can I test out the inferences and associated assumptions that I am making?

- What are the consequences of making the wrong conclusions?

- What is the story I am telling myself?

- How far is my story removed from reality?

This can look deceptively simple but it's not easy and takes dedicated attention over time to build a habit and muscle memory. However, it's well worth the effort and can have a ratcheting effect on multiple aspects of your leadership.

Related Reading

In this article, I focused on the ladder of inference from a decision-making perspective. It's an equally effective tool for getting good at meetings, both as a show-runner and participant. Here are 9 rules for effective meetings using the ladder of inference.

Being aware of how we are coming across to others, especially in leadership is critical. Often others are aware of our shortcomings, but this information never reaches us due to social norms. A powerful framework to uncover blindspots is the Johari Window model.

Transitioning into leadership is often a challenge for technical experts. The ladder of inference highlights how social domains can be ambiguous to navigate and less black and white compared to technical domains. I did a deep dive into the challenges of technical experts and specialists transitioning into leadership.

The ladder of inference is an important tool that highlights the role language plays in how we interpret reality. Language is an under-utilized instrument of leadership. I examined its aspects critical to leadership in The Hidden Role of Language in Leadership Communication.

Sources

- Creating Great Choices by Roger Martin, Jennifer Riel.

- The Second Mountain by David Brooks.

- Dialogue by William Issacs.

- As referenced in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook by Peter Senge, Art Kleiner, Charlotte Roberts.

- Principles by Ray Dalio.

- Managing by Henry Mintzberg.

- Difficult Conversations by Bruce Patton, Douglas Stone, Sheila Heen.

- The Effective Executive by Peter Drucker.

- Article from Asana looking at the ladder of inference from a data perspective.