Over the past two decades, psychological safety has gotten significant traction both in academia and in real world applications. It’s one of the few frameworks coming out of research that’s been widely proven as critical to team performance.

A crucial aspect of this research is the role leaders play by how they frame a given situation. Leaders have an outsized influence on how things get interpreted, and the key skill is framing. Unfortunately, most leaders and managers are oblivious to the importance of framing.

The importance of framing

Framing is a well researched and well understood phenomenon in the social and behavioral sciences. Yet most leaders are not adept at using it skillfully. Why is framing so important to understand?

- For one, people tend to copy leaders. They set the tone and are often looked up to for situational cues. Thus how a given situation gets interpreted often depends on leader's framing of that particular problem or challenge.

- Why is this important? In most complex situations that are ambiguous with no clear solutions, how the manager frames the challenge influences the team's actions. Did it come across as doable or as an impossible task? Did it come across as a challenge or a nagging problem to deal with?

Framing and performance

So why does this matter? One word: performance. Harvard professor Amy Edmondson [1,2] studied the implementation of a new innovative procedure across 16 different hospitals. The single most powerful factor that explained success or failure was how leaders framed the new initiative:

The difference between success and failure was not determined by management support, resources, project leader status, or expertise. Surprisingly, the difference wasn’t determined even by whether the hospital was academic, or by its prior history of innovation. Instead, differences in how the project was framed by each project leader gave rise to different attitudes about the technology and the need for teamwork.

A key insight from this work was that psychological safety is not a personality difference but rather a feature of the workplace that leaders can and must help create. More specifically, in every company or organization I’ve since studied, even some with famously strong corporate cultures, psychological safety has been found to differ substantially across groups. Nor was psychological safety the result of a random or elusive group chemistry.

What was clear was that leaders in some groups had been able to effectively create the conditions for psychological safety while other leaders had not. This is true whether you’re looking across floors in a hospital, teams in a factory, branches in a retail bank, or restaurants in a chain.

Framing influences and distorts

Skill in framing also matters because frames fundamentally influence and often distort how we see situations and thus ensuing actions:

Frames filter what we see. They control what information is attended to and, just as important, what is obscured. Remember: no single window can reveal the entire panorama.

Frames themselves are often hard to see. Just as we have to step back from a window to see that it’s there, so too do we have to “step back” from our frame to see that we are viewing the world through a particular perspective.

Frames appear complete. Frames simplify the world. They do not capture all of reality, leaving gaps. But since our mind tends to fill in such gaps, we usually don’t even notice that anything is missing.

Frames are exclusive. We typically see one frame at a time. It’s hard, after all, to simultaneously look out the windows on both the north and west sides of a room.

Frames can be “sticky” and hard to change. Once we are locked into a frame, it can be difficult to switch, especially without conscious effort. When people have emotional attachments to their frames, changing frames can seem threatening.

— Excerpt from Winning Decisions [5]

Framing enables psychological safety

Edmondson [1, 2], one of the foremost experts on psychological safety, identifies framing as the key step that sets the stage to create the right conditions for psychological safety that enables peak performance.

Whenever you are trying to get people on the same page, with common goals and a shared appreciation for what they’re up against, you’re setting the stage for psychological safety. The most important skill to master is that of framing the work.

One common leadership gaffe is of making the assumption that what needs to be done, or what approach is best, is obvious to everyone. For most non-technical scenarios, it's not. Each situation can have different focal points, and it's the frame that leaders create that determines what those focal points are.

If near-perfection is what is needed to satisfy demanding car customers, leaders must know to frame the work by alerting workers to catch and correct tiny deviations before the car proceeds down the assembly line.

If zero worker fatalities in a dangerous platinum mine is the goal, then leaders must frame physical safety as a worthy and challenging but attainable goal.

If discovering new cures is the goal, leaders know to motivate researchers to generate smart hypotheses for experiments and to feel okay about being wrong far more often than right.

So what are frames and how can leaders get better at it?

📚 HBR 100 Best Reads: You also get a curated spreadsheet of the best articles Harvard Business Review has ever published. Spans 70 years, comes complete with categories and short summaries.

What is framing

Framing is a natural aspect of being a human and operating in complex reality. It's an automatic process that we do on a regular basis but are often unaware of. It's useful to understand some of the nuances of frames.

Framing effects

Consider this classic example by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman [4] that shows how reality is subjective and not as objective as we are prone to think:

Italy and France competed in the 2006 final of the World Cup. The next two sentences both describe the outcome: “Italy won.” “France lost.” Do those statements have the same meaning? The answer depends entirely on what you mean by meaning.

For the purpose of logical reasoning, the two descriptions of the outcome of the match are interchangeable because they designate the same state of the world. As philosophers say, their truth conditions are identical: if one of these sentences is true, then the other is true as well. This is how Econs understand things. Their beliefs and preferences are reality-bound. In particular, the objects of their choices are states of the world, which are not affected by the words chosen to describe them.

There is another sense of meaning, in which “Italy won” and “France lost” do not have the same meaning at all. In this sense, the meaning of a sentence is what happens in your associative machinery while you understand it. The two sentences evoke markedly different associations.

“Italy won” evokes thoughts of the Italian team and what it did to win. “France lost” evokes thoughts of the French team and what it did that caused it to lose, including the memorable head butt of an Italian player by the French star Zidane. In terms of the associations they bring to mind—how System 1 reacts to them—the two sentences really “mean” different things. The fact that logically equivalent statements evoke different reactions makes it impossible for Humans to be as reliably rational as Econs.

Kahneman calls these framing effects:

Different ways of presenting the same information often evoke different emotions. The statement that “the odds of survival one month after surgery are 90%” is more reassuring than the equivalent statement that “mortality within one month of surgery is 10%.” Similarly, cold cuts described as “90% fat-free” are more attractive than when they are described as “10% fat.” The equivalence of the alternative formulations is transparent, but an individual normally sees only one formulation, and what she sees is all there is.

Two types of frames

It's essential to understand two different kinds of frames:

- One can be called "worldviews" which are global and that we borrow from culture and upbringing.

- The second type is local and more specific to a given situation that we actively construct.

Russo and Schoemaker [5] differentiate them as thinking frames and constructed frames:

The terms “frame” and “framing” have their origin in the academic fields of cognitive science and artificial intelligence.

...

An adult brain contains thousands of mental models, which have developed over decades of education and experience. Much of decision-makers’ special knowledge about their professional activities may be represented as a collection of mental models.

Frames are at the tightly woven structural core of these mental models, what we might call the mental model’s “essence.” They often reside in our memories and are usually evoked or triggered automatically. Whereas trying to change any substantial portion of a mental model can take weeks, months, even years, because of the vastness and strength of its interconnected network, frames can be exposed, understood, and realigned in less time.

The frames we use can be either borrowed or constructed. Every culture teaches powerful thinking frames (such as democracy) to its young. We unconsciously borrow these frames and apply them to diverse situations. A person’s occupation and education, capturing years of training and experience (e.g., learning how to think like a lawyer, engineer, or accountant), similarly produce powerful thinking frames. They become a permanent part of our mental repertoire, and we use them broadly. In fact, many thinking frames become so deeply ingrained in groups or organizations that people cannot change them when the circumstances call for it. When large groups use these widely shared mental models to define their reality, we call them paradigms.

In contrast to the broad thinking frames that we internalize through years of socialization and then borrow to apply to a wide range of situations, we sometimes construct frames to organize our thinking about a specific topic, situation, or decision. For example, when we develop criteria to evaluate possible vacation options, whom to hire for a job opening, or where to open a new retail outlet, we may construct a frame tailored to the problem and decision at hand. Although thinking frames and constructed frames differ in their origin and depth, their impacts on our decision-making processes bear enough similarities that we can talk about them together.

Werner Erhard puts it more simply:

While one’s worldview is relative to everything in one’s world, each of one’s frames of reference is relative to some specific something in one’s world. It is as though our worldview is a primary lens through which we view everything in our world. And, our various frames of reference are secondary lenses through which we view specific things in our world.

Frames as applied to leadership

Framing effects are a widely researched phenomenon in the social sciences, behavioral economics and cognitive psychology. But they are equally applicable to leadership. In her highly cited paper Framing for Learning (2003), Edmondson defines a frame as follows:

A frame is a set of assumptions and beliefs about a particular object or situation. The process of framing is a process of creating meaning—either passively and unconsciously or actively and consciously—that is not a necessary or factual aspect of that situation. Frames are shaped by past experiences in similar situations (or situations that seem similar in some way to those perceiving them) and affect both how we feel and how we think.

Framing is neither bad nor good; it is simply inevitable. We interpret what is going on around us through a lens shaped by our personal history and our current social context. The catch is, we tend to assume that our framing captures the truth, rather than presenting a subjective “map” of territory that could instead be mapped differently.

How to get better at framing

Given the importance of framing, what can leaders do to get better at it? Below are some basic strategies to get better at framing:

- Learn to uncover and identify frames

- Become familiar with common opposing frames

- Learn to leverage language forms

- Learn how to change the frame aka reframing

- Understand the role of context in leadership

Let's look at each of these.

1. Uncover and identify frames

Every decision, initiative or situation has an underlying frame whether we are aware of it or not. Use the following questions to uncover not just yours but other's frames as well:

- What do I consider as givens that go unquestioned? What frame do these assumptions support?

- What aspect does the frame address the most? What aspects does it ignore?

- What are the boundaries that the frame imposes? What do those boundaries leave out?

- What are the measures of success? Are they tailored to that particular situation? Do they encourage the behavior that you want to emphasize?

- What are the dominant metaphors and imagery being used to describe the issue? Are they working? If not, can you use another one instead?

- What behavior does the frame emphasize? What does it minimize?

- Can you borrow a different frame from a different discipline or industry?

- How is my background and training influencing my frame?

- What do you consider as non-negotiables?

- What are the "undiscussables"?

2. Common primary opposing frames

Some frames tend to be more common than others and it's useful to be aware of them. They often lie on a spectrum and are in tension with their polar opposites. Most of the time one tends to be the dominant which automatically makes the other secondary. Consider the following:

- Learning vs performing

- Goal-achieving vs self-protecting

- Health-enhancing vs health-limiting

- Positive vs negative

- Promotion vs prevention

- Growth vs fixed mindset

- Optimistic vs pessimistic

- Win-lose vs win-win

- Competition vs cooperation/coopetition

- Cost vs investment

- Maximizing gain vs minimizing loss

- Global vs local

- Past vs present vs future

- Transactional vs relationship based

- Contractual vs community based

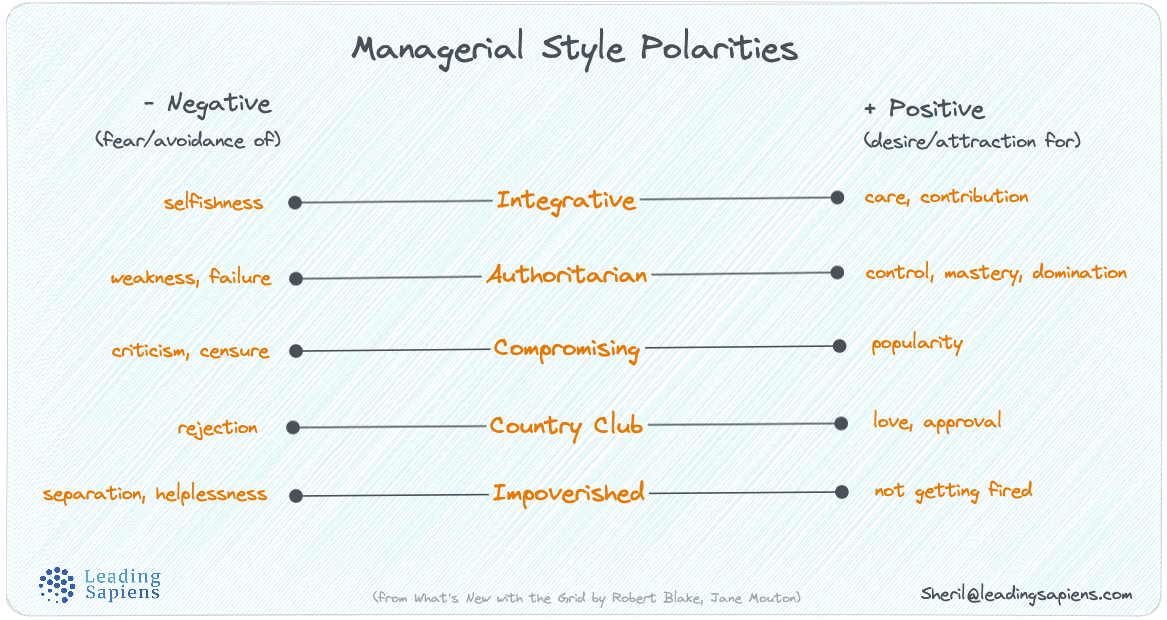

Often you will notice that these opposing polarities exist simultaneously. Thus framing gets even more critical as it drives which aspects get attention. As it turns out paradoxes are all too common in organizations and an often misunderstood aspect of the nature of managerial work.

3. Leveraging language to create and change frames

Gail Fairhurst outlines commonly used forms of language that leaders can use to frame and reframe more effectively:

Metaphorical language portrays a subject’s resemblance to something else that is not literally applicable.

Story frames a subject through narrative.

Contrast describes a subject in terms of what it is not.

Spin places a subject in a positive or negative light.

Jargon or catchphrases frame a subject in familiar terms.

Analogy frames a subject’s parallels to another subject.

Argument frames a subject in reasoned, rational terms.

Feeling statements frame a subject in terms of felt emotions.

Categories frame a subject in terms of its membership (or not) in a category and of category limits.

Three-part lists organize a subject in easily remembered “threes.”

Repetition dramatizes a subject through parallel form.

4. Learn how to reinforce and reframe

In her book Teaming, Amy Edmondson gives tactics for reinforcing a frame and for individual reframing.

Tactics for reinforcing a learning frame:

Use verbal and visual discourse to promote the learning frame.

Reinforce this framing by explaining and modeling the desired interpersonal and collaborative behaviors.

Explain these desired behaviors in practical terms, such as “Speak up if you see something wrong” or “Just pick up the phone and ask if you have a question.”

Initiate activities, for example, a kick-off meeting, a meeting to identify personal goals within the teaming or learning effort, and training on how to efficiently deal with interpersonal conflict. These can facilitate new processes or routines and help team members build confidence.

Use artifacts such as a prominent sign in the project work area to visually reinforce the learning frame.

Tactics for individual reframing:

Tell yourself that the project is different from anything you’ve done before and presents an exciting opportunity to try out new approaches and learn from them.

See yourself as critical to a successful outcome and yet as unable to achieve success without the willing participation of others.

Tell yourself that others are vitally important to a successful outcome and may provide key knowledge or suggestions that you can’t anticipate in advance.

Communicate with others exactly as you would if the above three statements were true.

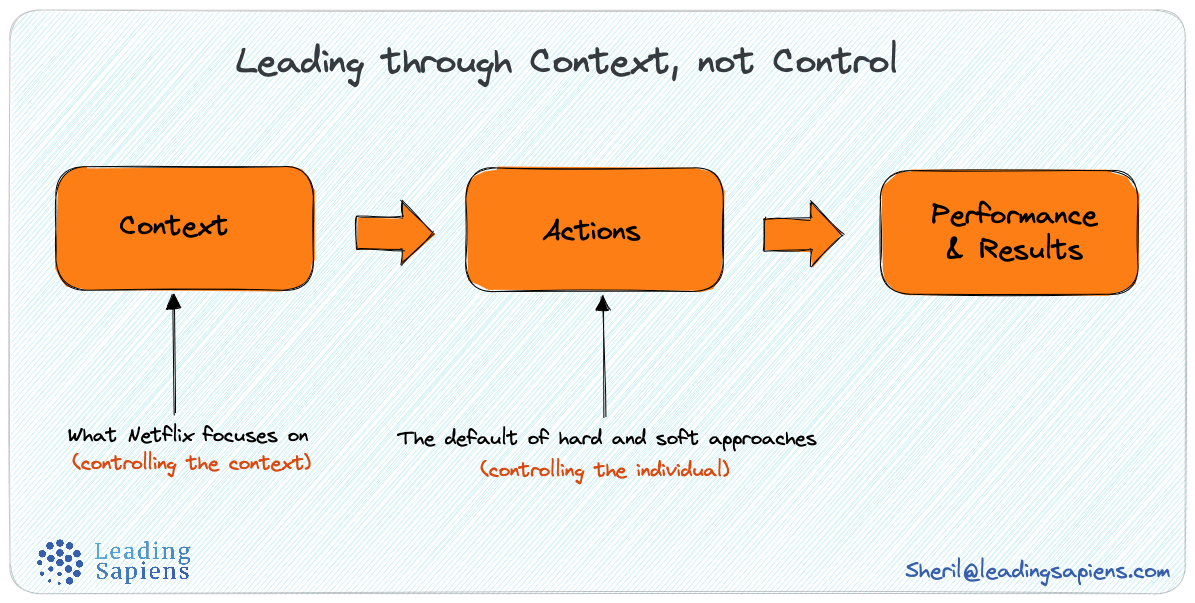

5. Understand the role of context

Learning to use context effectively is a key aspect of effective leadership, and framing is one way of managing context. Netflix is a good example of implementing context at the organizational level.

Another factor that influences your ability or inability to set the right context and frame is your leadership style. All leaders have a default approach. Being aware of your blindspots can help immensely.

📚 You also get a curated spreadsheet of 100 best articles Harvard Business Review has ever published. Spans 70 years, comes complete with categories and short summaries.

Sources and references

- Teaming by Amy Edmondson

- The Fearless Organization by Amy Edmondson

- Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Framing for Learning: Lessons in Successful Technology Implementation. California Management Review, 45(2), 34–54.

- Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- Winning Decisions by J. Edward Russo and Paul J.H. Schoemaker

- The Power of Framing by Gail T. Fairhurst

- Video: Amy Edmondson talking about how anyone can create psychological safety, not just leaders: