Most advice on leadership communication focuses on getting better at advocacy – crafting the message, effective delivery, and so on. What leaders forget is to balance their advocacy with equal amounts of inquiry. How are the two different and why does it matter? I take a closer look at the critical leadership skill of balancing advocacy and inquiry.

What is Advocacy

Many of us are told to "be more assertive". However, this well-meaning advice, when taken to its logical extreme, is anything but effective. Most common interpretations of being more assertive simply leads to the person increasing what Harvard and MIT researchers Chris Argyris and Donald Schon called advocacy.

Put simply, advocacy means putting forward our views directly and working to convince others of their validity. In pure advocacy mode, the primary focus is on stating and going to bat for our own standpoint, being vocal about them and defending it.

Most generic advice teaches getting better at advocacy — pushing, packaging, and polishing your own ideas and yourself. Notice how the focus is often on improving YOU– your delivery, style, viewpoint, even appearance, and so on.

The problem of too much Advocacy

Advocacy comes easier, especially to leaders and experts because :

- There’s a need to prove expertise.

- The notion that they have to persuade, pitch and inspire.

- We are not comfortable with silence, so we talk.

- We are naturally enthusiastic about our viewpoints, and averse to opposing viewpoints.

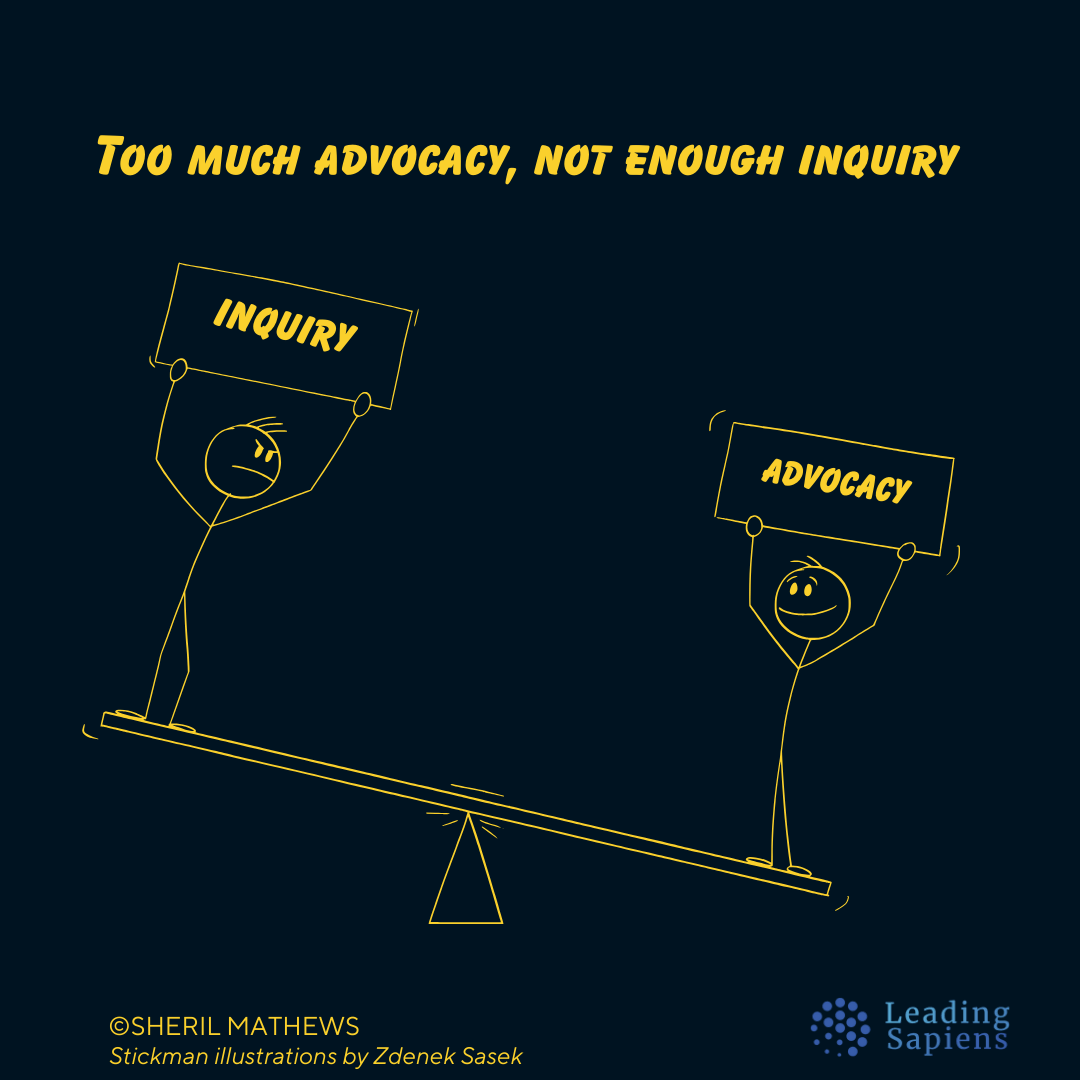

Because of this cultural bias, we are essentially skewed in our approach— too much advocacy and not enough inquiry.

This undue focus on advocacy works for the most part.

But it also means we inevitably hit a point where increased advocacy alone simply won’t cut it. In fact, too much of advocacy instead of increasing resonance with our message has the opposite effect of increasing resistance.

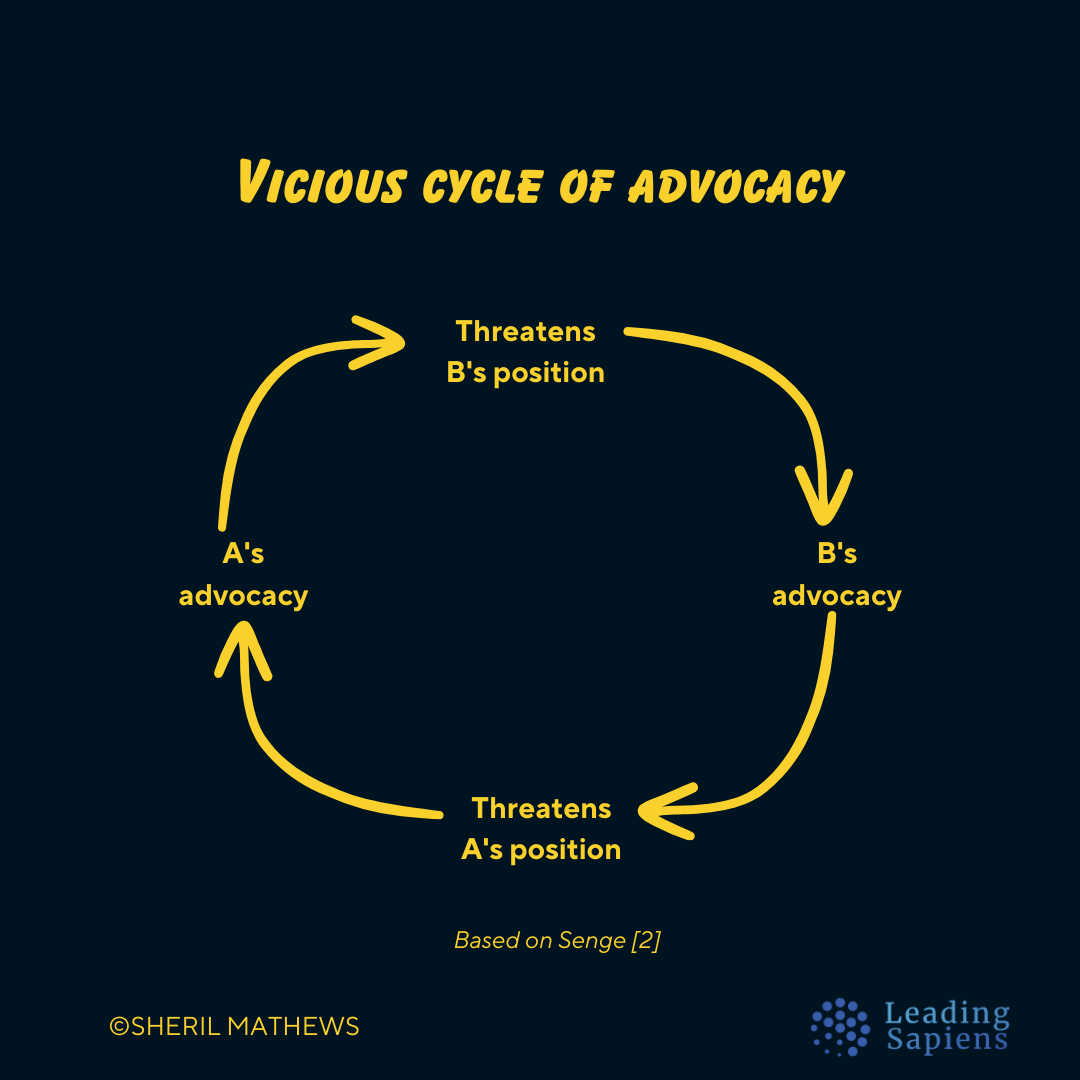

It starts a vicious cycle. Because increasing advocacy, without enough inquiry, means we don’t understand the other’s position and in fact threaten it. This causes them to increase their own advocacy, leading to an increasing spiral of opposition and resistance.

This dynamic ultimately leads to entrenched positions lacking in trust and leading to an impasse. It’s one reason why teams often feel unheard and don’t have buy-in into new initiatives pushed from the top-down.

So how can we get better at advocacy and prevent triggering this vicious cycle?

The antidote is twofold:

- getting better at advocacy itself, and

- increasing inquiry that balances out and informs our advocacy

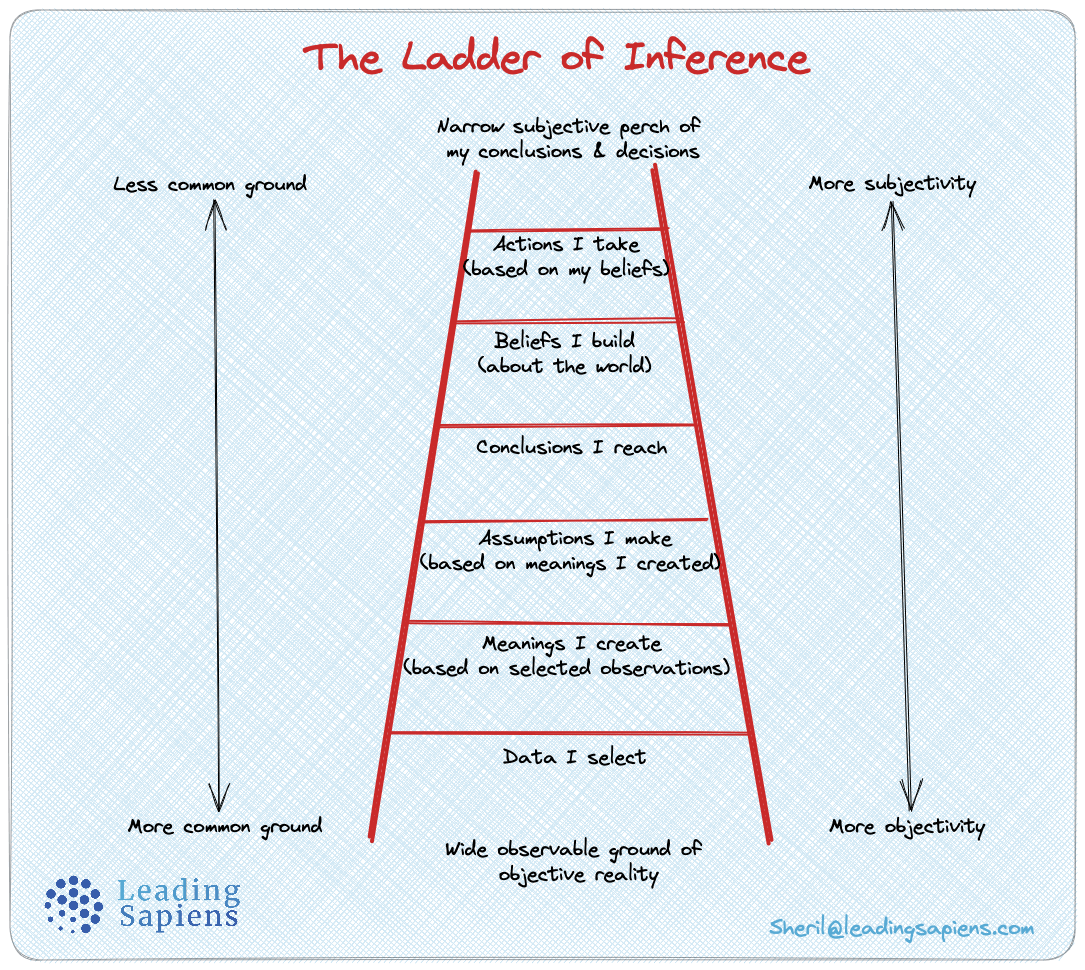

Advocacy when done well leverages key aspects of the ladder of inference. Bill Noonan [4] describes it this way:

Advocacy is essentially the Ladder of Inference in action. Spoken statements disclose the data selected as important, the meaning attached, and the conclusion drawn. The immediate effect on a business conversation is that the focus shifts from general, vague abstractions that are prone to misunderstandings and miscommunications to concrete, clear statements containing data-rich information. The results are

• Ideas that remain agile and innovative

• Increased levels of shared understanding for goals, ideas, and plans

• Clear, more compelling communication

Let's look at the second aspect which is increasing inquiry.

What is Inquiry

Inquiry is less common but in many ways a lot more crucial than advocacy. It happens when we ask questions to gain clarity on the other’s expressed opinions or positions. It’s about exploring their perspectives and scrutinizing our own to deepen mutual understanding.

Balancing advocacy requires expressing strong opinions while remaining open to opposition. We assert our views clearly and encourage others to contest them. The balance is maintained by genuinely attempting to comprehend and appreciate the reasoning behind others' viewpoints, and by a willingness to reassess our own assumptions.

Bill Noonan [4] defines inquiry as:

…a skill of asking well-crafted questions to discover more information in others’ views or invite challenge to one’s own viewpoint. Through the effective practice of inquiry, members of an organization will be better able to invite challenge to their own thinking and collect the best possible thinking available in their organization. The results are

• Faster discovery and correction of errors

• The ability to draw more information from another’s perspective

• Broader group learning through the surfacing of diverse perspectives

Persuasion is often couched in the context of charm and what we do and think, instead of understanding and what “they” do and think. There is as much logic and depth in the other’s view as in yours, and also more common ground between the two views than we are used to thinking.

Inquiry is very different from just plain “listening”, and then waiting your turn to restart your advocacy. It’s about getting into “their shoes” and seeing their viewpoint.

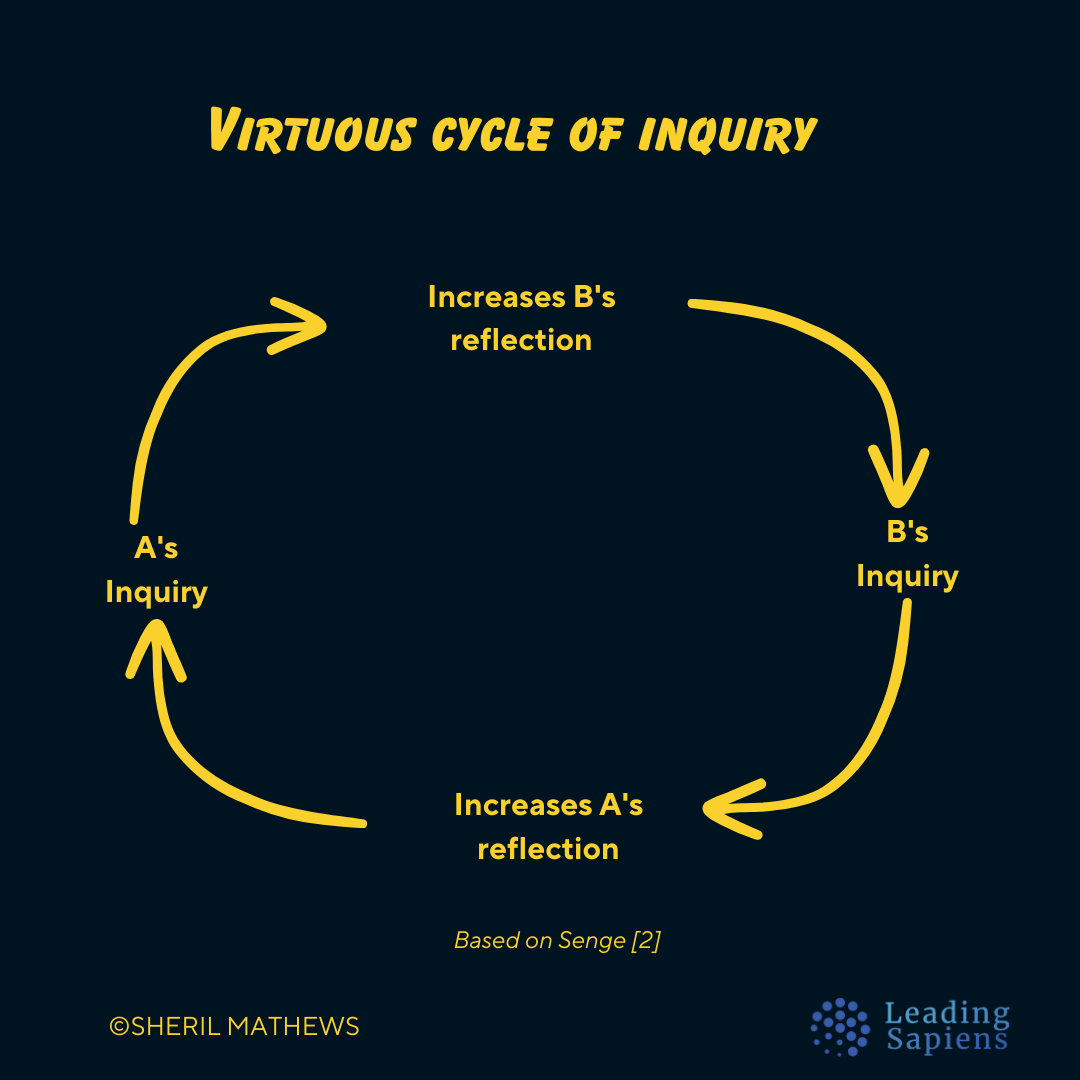

What’s interesting about inquiry is that the more you do it, the more effective your advocacy becomes. Your inquiry increases reflection on the part of others, which in effect creates a virtuous cycle different from the vicious cycle of advocacy.

By acknowledging and understanding differing viewpoints, we are making them part of our argument and in effect strengthening, not weakening our position. And this goes against how we are often taught to think in terms of debate and argument instead of a generative dialogue that creates possibilities.

Fames strategist Roger Martin calls this approach assertive inquiry.

Balancing Advocacy and Inquiry

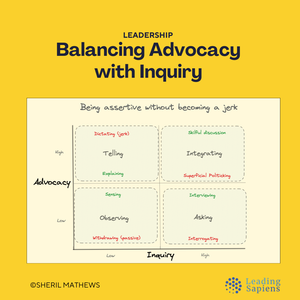

When focussed exclusively on advocacy we get the two extremes of:

- Passive (not enough)

- Assertive (too much)

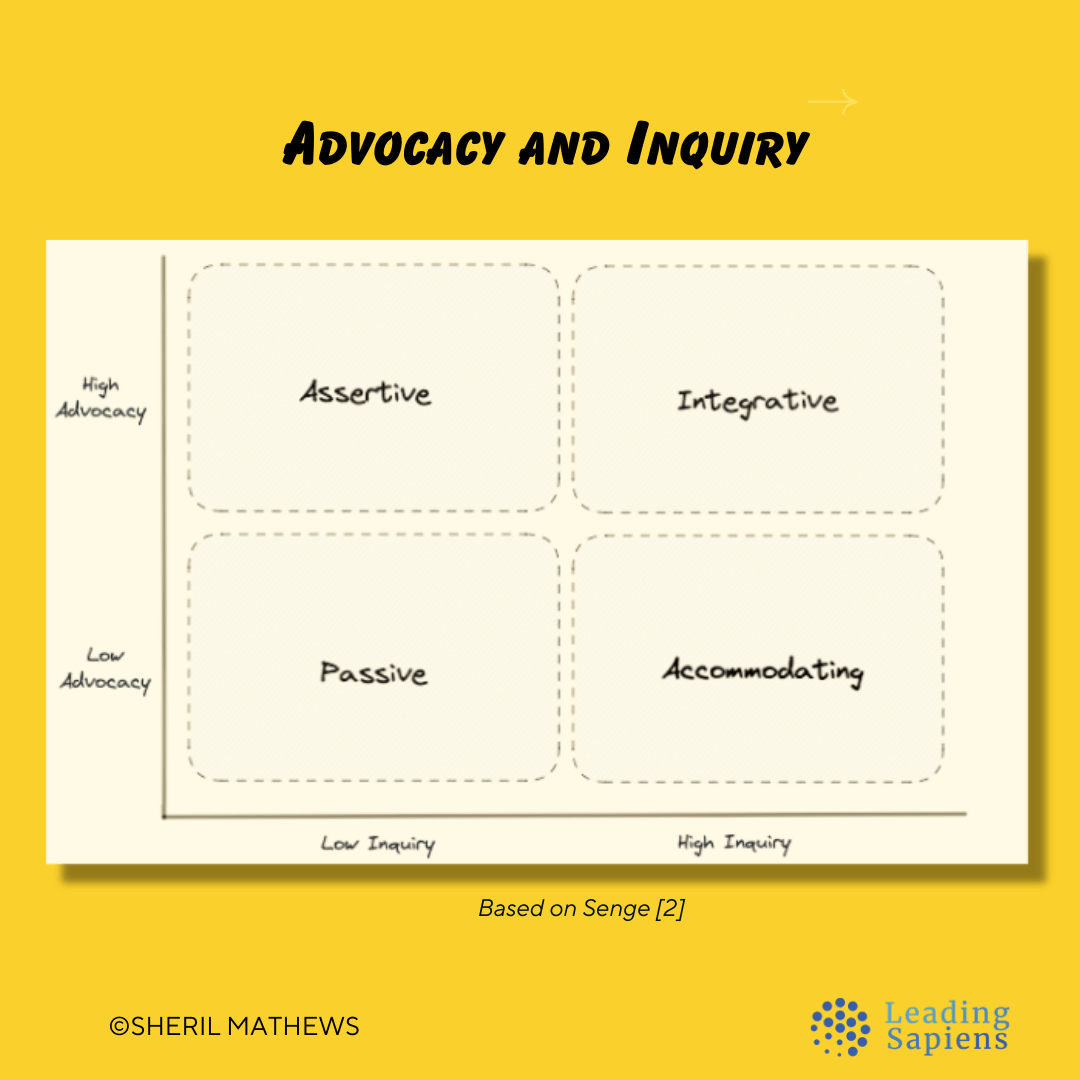

The moment you add INQUIRY into the picture, suddenly the range of available options increases. Mapping them gives the different modalities we can operate in each with its own pros and cons.

The matrix gives 4 primary modalities:

- Passive: Low Advocacy/Low Inquiry

- Assertive: High Advocacy/Low Inquiry

- Accommodating: Low Advocacy/High Inquiry

- Integrative: High Advocacy/High Inquiry

Bear in mind, none of these by themselves are bad or good. It depends on what the situation requires, and what will have the most impact.

The mistake is to operate exclusively in one mode. That's how your message doesn't go anywhere, or you end up in an impasse. Or the opposite of not being able to promote your agenda.

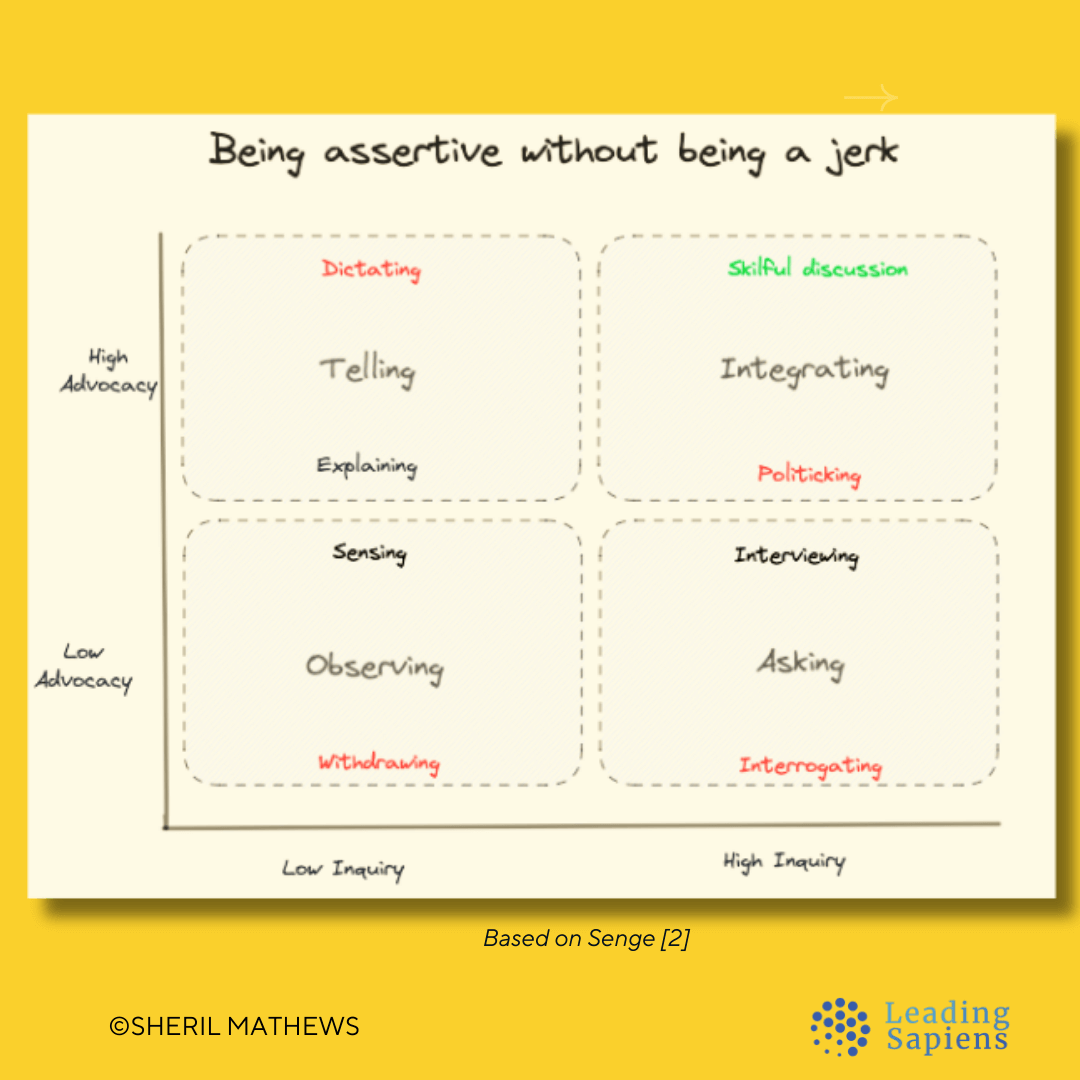

This means even within the 4 quadrants, there are effective and not so effective ways of approaching conversations. Each of the 4 quadrants has its own version of positive/negative, doing too much/too little, or with sincere/insincere intentions.

Some pointers:

- Observing is a better term for the "passive" stance. The extreme is of withdrawing, where there’s an unwillingness to expose our own thinking. The more skilled form is sense-making.

- In the classic telling (assertive) mode, the sensible version is explaining while the non-inquiry version is dictating without making your own reasoning visible.

- In the asking/accommodating mode — you can be interrogating by peppering someone with questions, or be more of a conversational interviewing mode.

- You can combine high advocacy and inquiry, but done insincerely and without an intent to learn, it becomes politicking. When done with skill and intent, it leads to a skillful discussion that integrates viewpoints and generates new possibilities.

- Business conversations typically fall into the high advocacy/low inquiry category. In such discussions, we impose our singular perspectives based on our own observations of a situation. To achieve better understanding and more possibilities, leaders have to shift towards a stance of high inquiry and low advocacy.

Everyone has a tendency for either advocacy or inquiry based on their background and natural inclinations. Studying the different modes and increasing awareness of your default approach is a good place to start making changes.

How to balance advocacy with inquiry

Below are some pointers for getting better at balancing advocacy and inquiry:

- Explain your point of view, including the reasoning behind how you got there.

- State your thoughts clearly and confidently, while also being receptive to the possibility of being incorrect.

- Invite others to ask questions about your standpoint. Encourage them to challenge your views while examining potential barriers that might deter them from doing so.

- Ask others genuinely about their perspective. Aim both to comprehend and to challenge the behaviors and motivations of others.

- Watch your question-to-talk ratio. Instead of providing answers, ask more questions to engage others, prompting them to think independently and arrive at their own conclusions. As they share their viewpoints, help them examine underlying beliefs and assumptions.

- Learn to articulate the thought process behind your statements. This goes against the common social practice of concealing such thoughts to avoid embarrassment.

Bill Noonan [4] gives the acronyms of STATE and ASK that are useful reminders of the basics of balancing advocacy and inquiry:

STATE (advocacy):

- Share your data.

- Tell others about your reasoning.

- Acknowledge your assumptions.

- Test your conclusions, rather than stating them as facts.

- Explore alternative interpretations of the data.

ASK (inquiry):

- Ask questions that surface reasoning and data.

- Search for alternative views.

- Keep your curiosity going.

Advocacy and inquiry in leadership

The skill of balancing advocacy with inquiry is especially critical to effective leadership. High performing leaders and their teams have a healthy ratio of advocacy and inquiry. Balancing the two also leads increases psychological safety.

But inquiry is rare. Why?

- Most places actively discourage inquiry. It’s often seen as a weakness while advocacy is seen as a strength.

- Many organizations are gladiatorial in nature where everyone is pitching and defending their own positions and agenda. In such competitive cultures, the primary objective is to win. Typical communication involves discussions where stakeholders staunchly advocate for their positions, leading to counterarguments from others.

- Leaders typically approach issues with a predetermined viewpoint or desired outcome that they actively promote. Their contributions are mainly aimed at advocating their own perspective. This dynamic often leads to others pushing back, prompting the original speaker to intensify their advocacy. As a result, positions become entrenched and discussions devolve into arguments where positions are thrown back and forth without genuine listening.

Effective communication

- Leaders must communicate clearly and persuasively to effectively advocate for their mission and stakeholders.

- But, leaders overlook the importance of being skilled in inquiry. Leadership communication is fraught with potential misunderstandings that can leave both leaders and their teams confused and frustrated. Leaders contribute to these challenges due to their own blind spots and a lack of awareness of fundamental skills — such as advocacy and inquiry — which are crucial for improving communication effectiveness.

- Being an effective leader is difficult without also being an effective listener and learner — essential traits for navigating the complexities of interpersonal communication.

Team dynamics

- The dynamics of inquiry and advocacy are significantly influenced by team size. In larger teams there’s a tendency for members to advocate more than inquire. Team members often feel uncertain about when they will have another opportunity to speak, prompting them to use their limited speaking time to state their position or make a point.

- Conversely, in smaller teams, people are more inclined to spend their time asking questions and seeking clarification, secure in the knowledge that they will have further opportunities to contribute their ideas and opinions.

Operating in complexity

- Without effective inquiry, plain advocacy can easily lead to groupthink. Being vocal and not entertaining opposing views can work in more predictable environments where solutions are known and best practices already identified. But in evolving situations, diversity of inputs and opinions is what leaders need.

- Successful individuals, especially in management, owe their achievements to the ability to develop and communicate ideas to captivate and convince others. However, inflexible advocacy becomes ineffective in the face of complex challenges that necessitate drawing on the collective intelligence of everyone involved.

Further Reading

- Many of the concepts described here build on the action science model called ladder of inference that Chris Argyris developed. It describes how our thought process works and is an excellent tool to get better at uncovering where we and others might be stuck.

- Another useful framework for effective communication is Aristotle's Ethos, Pathos, and Logos triad.

- Balancing advocacy and inquiry is especially relevant in meetings. Roger Schwarz has identified some ground rules for running effective meetings.

Sources

- Necessary Revolution by Peter Senge

- The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook by Peter Senge

- The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge

- Discussing the Undiscussable by William Noonan