In The Fifth Discipline, there's a useful primer on systems thinking that I keep going back to. Senge calls it the laws of the fifth discipline, or in other words, laws of systems thinking. [1]

Senge's ground-breaking book was published in the early 90s, and yet in the ensuing decades, things have been more same than different. They are a humble reminder of the reality that everyone faces in modern organizations.

Organizations are complex systems, and knowing some of the inherent dynamics can help understand them better. Being aware of the below tendencies helps to stay alert to avoidable mistakes, that are equally easy to forget.

1. Today’s problems come from yesterday’s “solutions.”

Once there was a rug merchant who saw that his most beautiful carpet had a large bump in its center. He stepped on the bump to flatten it out—and succeeded. But the bump reappeared in a new spot not far away. He jumped on the bump again, and it disappeared—for a moment, until it emerged once more in a new place. Again and again he jumped, scuffing and mangling the rug in his frustration; until finally he lifted one corner of the carpet and an angry snake slithered out.

Often we are puzzled by the causes of our problems; when we merely need to look at our own solutions to other problems in the past.

Solutions that merely shift problems from one part of a system to another often go undetected because, unlike the rug merchant, those who “solved” the first problem are different from those who inherit the new problem.

Often success in organizations is a function of outrunning the problems that you helped create. It's easy to get frustrated when you inherit "someone else's" issues. But we have to remind ourselves that others are dealing with problems that we might have created.

2. The harder you push, the harder the system pushes back.

Systems thinking has a name for this phenomenon: “compensating feedback”: when well-intentioned interventions call forth responses from the system that offset the benefits of the intervention. We all know what it feels like to be facing compensating feedback—...the more effort you expend trying to improve matters, the more effort seems to be required.

Many companies experience compensating feedback when one of their products suddenly starts to lose its attractiveness in the market. They push for more aggressive marketing; that’s what always worked in the past, isn’t it?

They spend more on advertising, and drop the price; these methods may bring customers back temporarily, but they also draw money away from the company, so it cuts corners to compensate. The quality of its service (say, its delivery speed or care in inspection) starts to decline. In the long run, the more fervently the company markets, the more customers it loses.

Pushing harder, whether through an increasingly aggressive intervention or through increasingly stressful withholding of natural instincts, is exhausting. Yet, as individuals and organizations, we not only get drawn into compensating feedback, we often glorify the suffering that ensues.

When our initial efforts fail to produce lasting improvements, we push harder—faithful...to the creed that hard work will overcome all obstacles, all the while blinding ourselves to how we are contributing to the obstacles ourselves.

3. Behavior grows better before it gets worse.

Low-leverage interventions would be much less alluring if it were not for the fact that many actually work, in the short term. ....Compensating feedback usually involves a “delay,” a time lag between the short-term benefit and the long-term disbenefit.

In complex human systems there are always many ways to make things look better in the short run. Only eventually does the compensating feedback come back to haunt you.

The key word is “eventually.” The delay ...explains why systemic problems are so hard to recognize. A typical solution feels wonderful, when it first cures the symptoms. Now there’s improvement; or maybe even the problem has gone away.

It may be two, three, or four years before the problem returns, or some new, worse problem arrives. By that time, given how rapidly most people move from job to job, someone new is sitting in the chair.

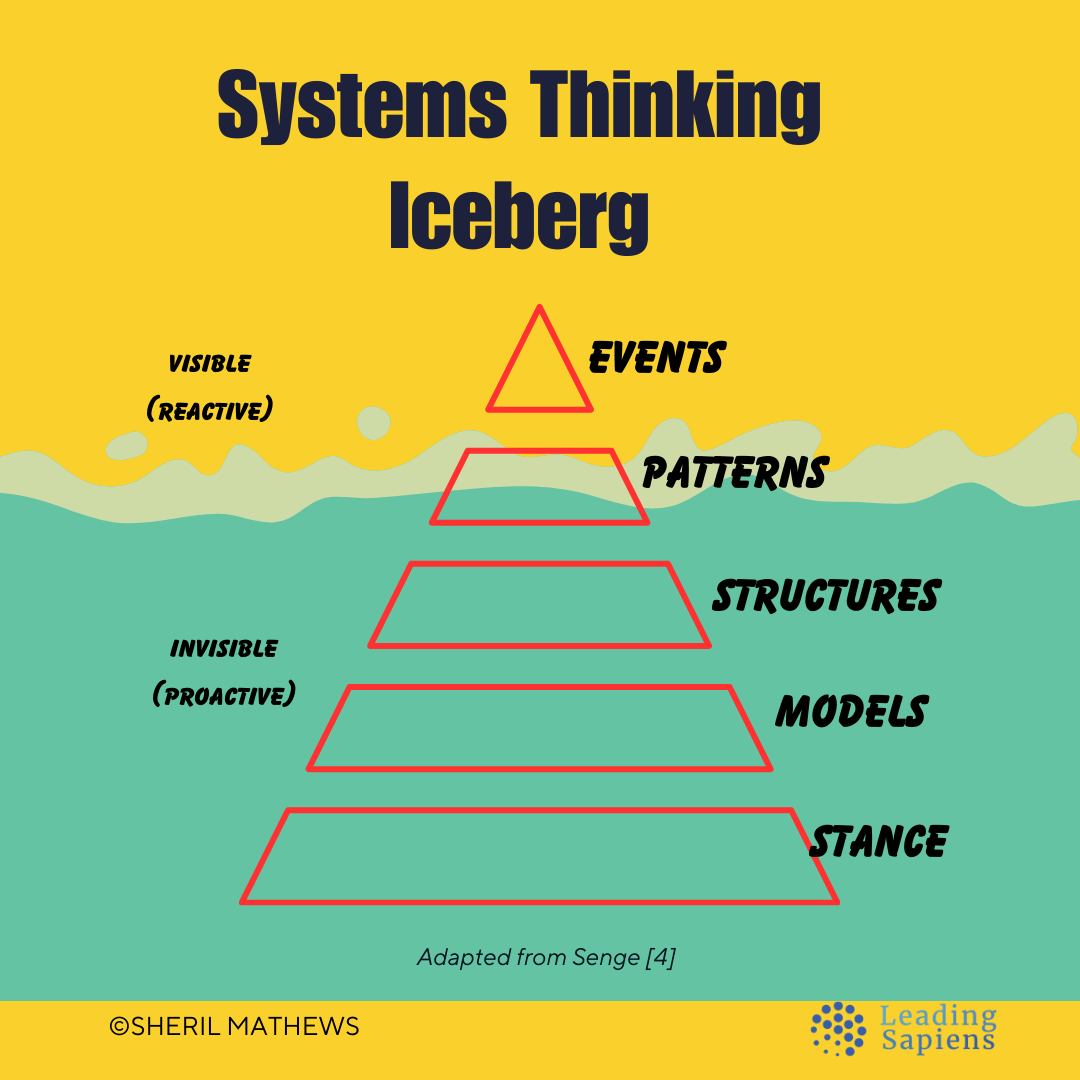

A useful to tool to detect and recognize systemic causes instead of being fixated on surface level issues is to use the iceberg model of systems thinking.

4. The easy way out usually leads back in.

We all find comfort applying familiar solutions to problems, sticking to what we know best. ...After all, if the solution were easy to see or obvious to everyone, it probably would already have been found.

Pushing harder and harder on familiar solutions, while fundamental problems persist or worsen, is a reliable indicator of nonsystemic thinking—what we often call the “what we need here is a bigger hammer” syndrome.

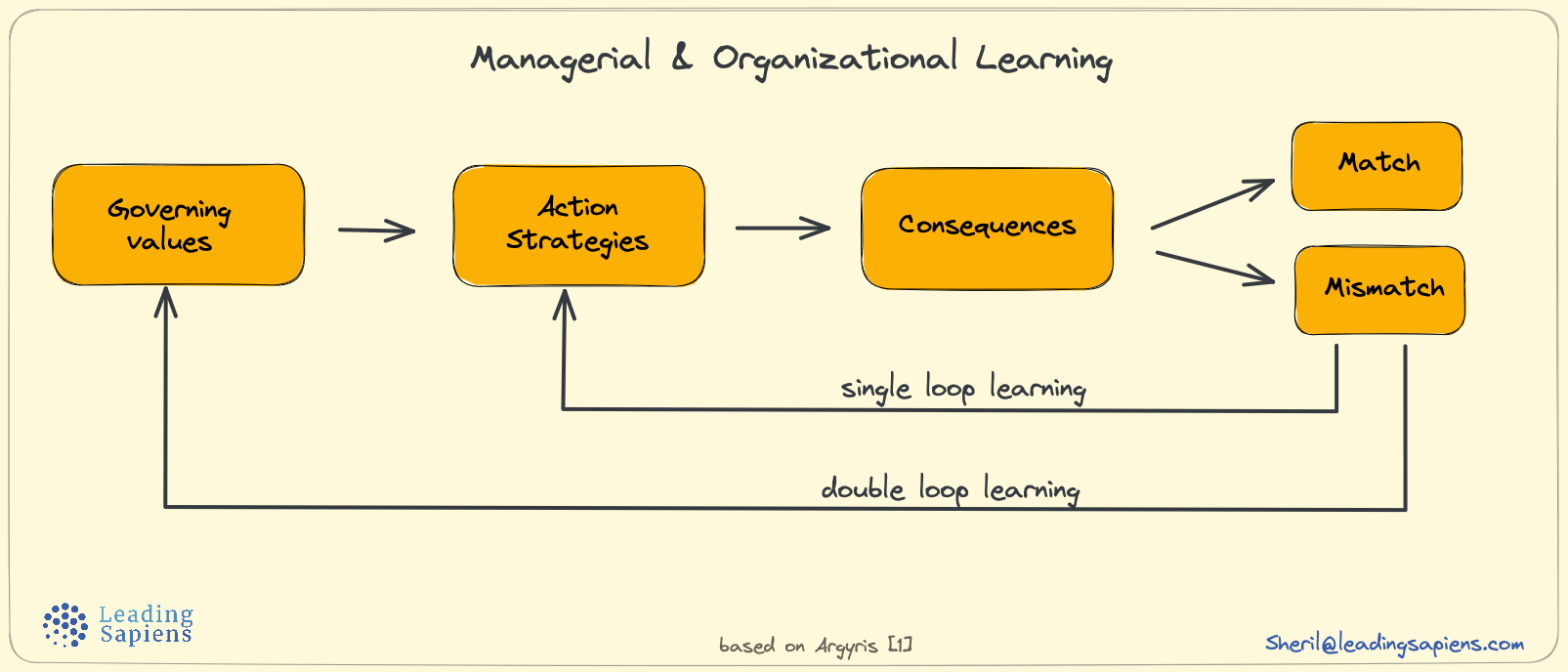

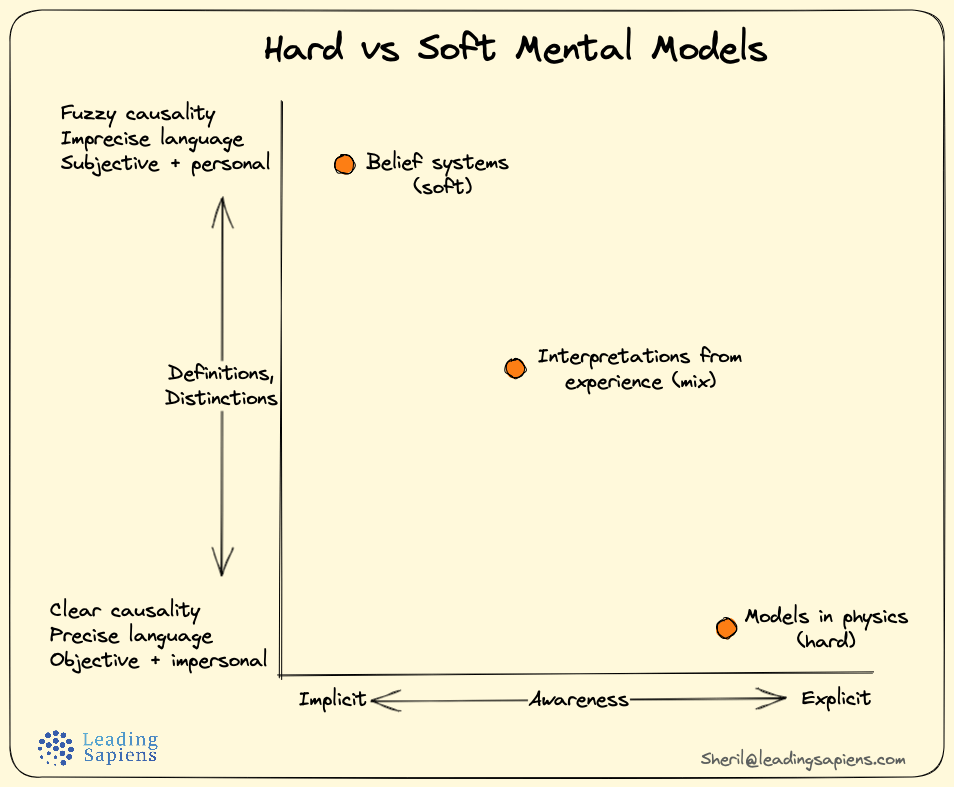

An effective way to counter this tendency is learning to think using the double-loop learning framework, and examining hidden mental models and questioning assumptions:

Another effective antidote is to focus more on problem-construction and problem-setting, instead of jumping head on into problem-solving.

5. The cure can be worse than the disease.

Sometimes the easy or familiar solution is not only ineffective; sometimes it is addictive and dangerous. Alcoholism, for instance, may start as simple social drinking—a solution to the problem of low self-esteem or work-related stress. Gradually, the cure becomes worse than the disease; among its other problems it makes self-esteem and stress even worse than they were to begin with.

The long-term, most insidious consequence of applying nonsystemic solutions is increased need for more and more of the solution.

A classic example of a non-systemic solution is using money exclusively to increase retention. As Senge points out, it might work initially, but eventually makes things worse, by needing more and more of the "medicine".

Frederick Herzberg differentiated this as the difference between hygiene factors and motivators – job satisfaction is not the polar opposite of job dissatisfaction, as is commonly understood. And neither are the factors that influence them.

The phenomenon of short-term improvements leading to long-term dependency is so common, it has its own name among systems thinkers—it’s called “shifting the burden to the intervenor.”

The intervenor may be federal assistance to cities, food relief agencies, or welfare programs. All “help” a host system, only to leave the system fundamentally weaker than before and more in need of further help.

In business, we can shift the burden to consultants or other “helpers” who make the company dependent on them, instead of training the client managers to solve problems themselves. Over time, the intervenor’s power grows—whether it be a drug’s power over a person, or the military budget’s hold over an economy...

6. Faster is slower.

This, too, is an old story: the tortoise may be slower, but he wins the race. For most American business people the best rate of growth is fast, faster, fastest.

Yet, virtually all natural systems, from ecosystems to animals to organizations, have intrinsically optimal rates of growth. The optimal rate is far less than the fastest possible growth. When growth becomes excessive—as it does in cancer—the system itself will seek to compensate by slowing down; perhaps putting the organization’s survival at risk in the process.

When it comes to human systems, speed is often the wrong criteria.

7. Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space.

Underlying all of the above problems is a fundamental characteristic of complex human systems: cause and effect are not close in time and space.

By “effects,” I mean the obvious symptoms that indicate that there are problems—drug abuse, unemployment, starving children, falling orders, and sagging profits. By “cause” I mean the interaction of the underlying system that is most responsible for generating the symptoms, and which, if recognized, could lead to changes producing lasting improvement.

Why is this a problem? ...most of us assume, most of the time, that cause and effect are close in time and space.

When we play as children, problems are never far away from their solutions...Years later, as managers, we tend to believe that the world works the same way. If there is a problem on the manufacturing line, we look for a cause in manufacturing. If salespeople can’t meet targets, we think we need new sales incentives or promotions.

...the root of our difficulties is neither recalcitrant problems nor evil adversaries—but ourselves. There is a fundamental mismatch between the nature of reality in complex systems and our predominant ways of thinking about that reality.

The first step in correcting that mismatch is to let go of the notion that cause and effect are close in time and space.

Another aspect of causality which throws us off is we forget to account for circular causality — rather than a simple linear cause and effect, the effects influence the cause, thus setting up a vicious/virtuous loop. In complex interactions, it's hard to discern what's causing what.

8. Small changes can produce big results, but the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious.

Some have called systems thinking the “new dismal science” because it teaches that most obvious solutions don’t work—at best, they improve matters in the short run, only to make things worse in the long run.

But...systems thinking also shows that small, well-focused actions can sometimes produce significant, enduring improvements, if they’re in the right place. Systems thinkers refer to this principle as “leverage.”

Tackling a difficult problem is often a matter of seeing where the high leverage lies, a change which—with a minimum of effort—would lead to lasting, significant improvement.

The only problem is that high-leverage changes are usually highly nonobvious to most participants in the system. They are not “close in time and space” to obvious problem symptoms. ...

There are no simple rules for finding high-leverage changes, but there are ways of thinking that make it more likely. Learning to see underlying structures rather than events is a starting point...

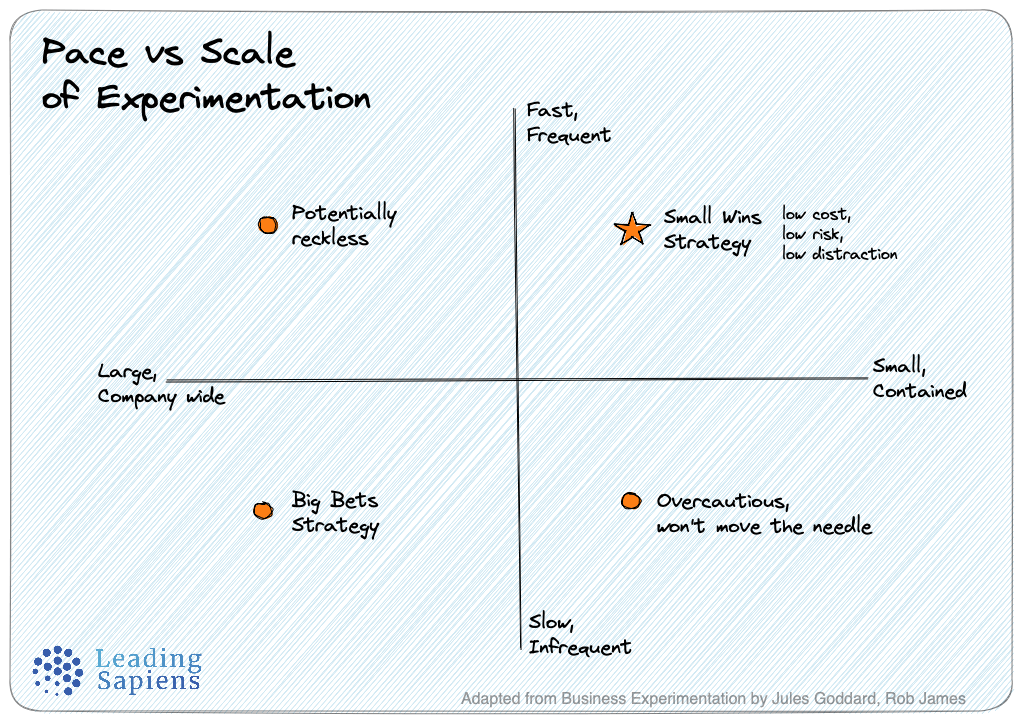

In addition to paying attention to structures, another effective way to use leverage is understanding the mechanisms of a small wins approach — they are small adaptations that are already working, but we are not noticing them because of size.

9. You can have your cake and eat it too, but not all at once.

Sometimes, the knottiest dilemmas, when seen from the systems point of view, aren’t dilemmas at all. They are artifacts of “snapshot” rather than “process” thinking, and appear in a whole new light once you think consciously of change over time.

For years, for example, American manufacturers thought they had to choose between low cost and high quality. “Higher quality products cost more to manufacture,” they thought. “They take longer to assemble, require more expensive materials and components, and entail more extensive quality controls.”

What they didn’t consider was all the ways that increasing quality and lowering costs could go hand in hand, over time. What they didn’t consider was how basic improvements in work processes could eliminate rework, eliminate quality inspectors, reduce customer complaints, lower warranty costs, increase customer loyalty, and reduce advertising and sales promotion costs. They didn’t realize that they could have both goals, if they were willing to wait for one while they focused on the other.

Many apparent dilemmas, such as central versus local control, and happy committed employees versus competitive labor costs, and rewarding individual achievement versus having everyone feel valued, are by-products of static thinking. They only appear as rigid “either-or” choices, because we think of what is possible at a fixed point in time.

Dichotomous thinking pervades in business settings. What makes it worse is that many organizational setups are paradoxes, which by definition cannot be resolved. The trick is to recognize them, and instead of fighting them, learn to operate within the tensions that they generate.

10. Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two elephants.

Living systems have integrity. Their character depends on the whole. The same is true for organizations; to understand the most challenging managerial issues requires seeing the whole system that generates the issues.

...

The key principle, called the “principle of the system boundary,” is that the interactions that must be examined are those most important to the issue at hand, regardless of parochial organizational boundaries.

What makes this principle difficult to practice is the way organizations are designed to keep people from seeing important interactions.

...

Incidentally, sometimes people go ahead and divide an elephant in half anyway. You don’t have two small elephants then; you have a mess. By a “mess,” I mean a complicated problem where there is no leverage to be found because the leverage lies in interactions that cannot be seen from looking only at the piece you are holding.

11. There is no blame.

We all tend to blame someone else—the competitors, the press, the changing mood of the marketplace, the government—for our problems. Systems thinking shows us that there is no separate “other”; that you and the someone else are part of a single system. The cure lies in your relationship with your “enemy.”

Sources and references

- The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge

- Senge references the following sources:

These laws are distilled from the works of many writers in the systems field:

‣ Garrett Hardin, Nature and Man’s Fate

‣ Jay Forrester, Urban Dynamics

‣ Jay Forrester, “The Counterintuitive Behavior of Social Systems”

‣ Donella H. Meadows “Whole Earth Models and Systems”

‣ Draper Kauffman, Jr., Systems I: An Introduction to Systems Thinking

‣ Sufi tales can be found in the books of Idries Shah, eg., Tales of the Dervishes and World Tales

‣ George Orwell, Animal Farm

‣ D. H. Meadows, “Whole Earth Models and Systems”

‣ Lewis Thomas, The Medusa and the Snail

‣ Charles Hampden Turner, Charting The Corporate Mind: Graphic Solutions to Business Conflicts