Understanding and using power is key to effective leadership. The French-Raven model of power bases is a good primer on the different types of power. This post introduces this foundational framework of power and the 6 types: coercive, reward, legitimate, expert, referent, and information power.

In 1959, social psychologists John French and Bertram Raven changed our understanding of leadership forever. Their groundbreaking work on different types of power continues to shape how we understand power and influence in organizations today.

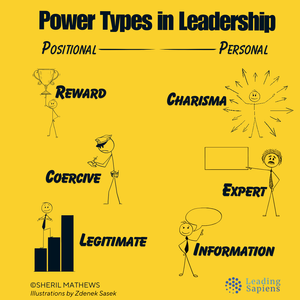

French and Raven identified five core types of power: reward, coercive, legitimate, expert, and referent (charismatic). Later, a sixth type, informational, was added.

These aren't just theoretical concepts. Consider the managers you've encountered:

- The incentivizer: When a manager promises promotions or bonuses, they're tapping into reward power.

- The enforcer: If they threaten demotion or job loss, that's coercive power at work.

- The influencer: A leader who relies on relationships and charisma is exercising referent power.

- The authority figure: When someone makes decisions "because I'm the boss," that's legitimate power in action.

- The subject matter expert: A manager who leverages their superior knowledge is using expert power.

- The master communicator: A manager who skillfully shares knowledge and persuades through well-crafted messages is exercising information power.

Understanding the underlying power dynamics helps to navigate workplace relationships more effectively and develop leadership capacity. The French-Raven model is a solid foundation for leaders to understand power.

But before we start, why bother at all?

Why should leaders study power?

Power often has a negative connotation, leading many to ignore it. But those who grasp its subtleties can:

- Navigate complex organizational structures more effectively.

- Motivate and influence team members better.

- Build stronger stakeholder relationships.

- Make informed decisions.

- Resolve conflicts more effectively.

- Adapt their leadership style to different situations.

Using power doesn't make you Machiavellian. In fact, it's the opposite – it makes you a more conscious, ethical leader because it helps you recognize and mitigate abuses of authority, creating a balanced work environment of trust and collaboration. Power is one of the many paradoxes of leadership and management.

As Raven noted from his research:

It is reasonable to conclude that a leader who is more aware, either formally or informally, of the various options in social power strategies will be more successful and effective. [2]

It’s imperative for leaders to understand their own capabilities and limitations when dealing with others. A thorough grasp of the interplay of power, influence, and authority is necessary groundwork for effective leadership.

Let’s examine the six types of power.

The six types of power

Reward power

This comes from the ability to offer something desirable, whether material or psychological, to induce compliance or action. In organizations, reward power is seen in promotions, bonuses, or informal rewards like praise and recognition. It is effective as long as people value the reward and believe the leader can deliver it.

However, the power of rewards is not limitless. Overuse leads to diminishing returns as recipients begin to expect them or become motivated purely by extrinsic factors, undermining intrinsic motivation. The quality and consistency of the rewards also matter; a reward perceived as insufficient or inconsistent erodes trust and reduces the effectiveness of this power base.

These nuances appear in Herzberg’s hygiene vs motivation theory that differentiates between factors that prevent dissatisfaction (hygiene) and those that actively motivate (motivation). Reward power includes both, but is most effective when aligned with motivation factors.

Coercive power

This power relies on punishments or negative consequences. Coercive power is the most direct and explicit because it creates a clear link between non-compliance and punishment. Common forms include demotions, reprimands, or exclusion from group benefits.

Coercive power can lead to immediate compliance, but its long-term effectiveness is limited. Over-reliance on coercion creates resentment, rebellion, or passive resistance. It requires constant monitoring, as compliance drops when surveillance is relaxed. In extreme cases, it damages relationships and trust, creating conflict and a toxic work environment.

Legitimate power

Often called “positional power,” legitimate power comes from your formal role and title. It’s grounded in the perception that the authority figure has the right to make demands and that others must comply due to their role. For example, a manager’s power over employees or a teacher’s authority in the classroom.

Cultural and organizational norms strengthen legitimate power. In hierarchical organizations, people are socialized to respect the chain of command. However, the boundaries of the role limit it; authority figures who overstep risk losing their legitimacy. It is more effective in formal settings, while in informal groups, its influence varies.

Expert power

This type of power comes from the leader’s knowledge, skills, or expertise that others need or respect. Expert power is strong in situations where specialized knowledge is critical. A software developer with deep knowledge of a specific programming language holds expert power over colleagues unfamiliar with that language.

Expert power leads to voluntary compliance, as others view the expert as a valuable resource. However, its effectiveness depends on perceived credibility and relevance of the expertise. If your knowledge is seen as outdated or unreliable, its power diminishes. It is also situation-specific; you may hold significant expert power in one context but very little in another.

A leader’s perceived expertise helps legitimize their role. Group members are more likely to follow someone they deem competent. Conversely, a lack of expertise undermines the leader’s position.

Referent power

Also known as charisma, referent power is based on admiration for, or a desire to emulate someone. It is the sheer force of personality. This type of power is seen in charismatic leaders where people comply to align with the leader’s values, behaviors, and identity.

Referent power is unique because it is deeply personal and involves emotional attachment. It creates strong, lasting influence, as followers internalize the leader’s values and behaviors. However, it is also fragile; a significant lapse in judgment or perceived betrayal can rapidly erode it.

If people idealize the leader too much, losing sight of their own values, it creates unhealthy dynamics.

Informational power

Informational power involves using facts, logical arguments, or persuasive communication to influence others. Unlike the other bases, it is transient—it exists as long as the leader possesses exclusive or superior information. Once the information is shared or widely known, this power dissipates.

It’s effective in situations requiring persuasion rather than coercion. In negotiations, providing clear, convincing information can shift the balance of power. However, its effectiveness depends on the information’s accuracy and relevance. Misleading or irrelevant information can backfire, damaging your credibility.

Nuances of the types of power

Understanding the six types of power is crucial. It's equally important to recognize the nuances in how they operate and interact. Here are a few:

Personal vs positional

Reward, coercive, and legitimate powers are categorized as "position power" since they come from your formal role in an organization and are exclusive to managerial positions. Conversely, expert and referent powers are classified as "personal power" because they derive from individual qualities and are available to anyone using these methods.

Effective vs ineffective leaders

In real-world scenarios, influence requires multiple power bases working together. An effective leader might rely equally on legitimate position, expert knowledge, and personal appeal to sway followers based on the context. In contrast, ineffective ones rely heavily on only one or two approaches while neglecting others, lacking the broad repertoire of their more effective counterparts.

Leaders with higher self-confidence are more likely to use informational and expert power, while those with lower self-efficacy rely on coercive and legitimate power. Research shows that insecure individuals overcompensate by using harsher strategies. In contrast, those with greater self-assurance use more nuanced forms of power.

Coercive power should be used minimally, but leaders must be willing to use it judiciously if necessary.

Stage setting

Raven highlighted the importance of stage-setting for successful influence. Strategies often fail when the audience isn’t psychologically or emotionally prepared. For instance, a physician might display their diplomas prominently to enhance expert power before making a recommendation to a patient.

Other tactics include ingratiation (offering compliments or small favors) or self-promotion (emphasizing achievements to bolster expert power). By setting the stage effectively, the leader creates a context to leverage their power base.

A similar idea is how framing increases psychological safety.

Mode and tone

The tone of power matters. An aggressive tone can weaken a persuasive argument, while a weak argument may gain power when delivered with care.

Informational influence can encourage compliance or trigger resistance, depending on its presentation. If done in a helpful and cooperative tone, it inspires trust. Conversely, if it’s delivered harshly or accompanied by fear appeals, such as a doctor using graphic images to warn a patient about smoking, it generates anxiety and defensiveness rather than change.

Aristotle’s ethos, pathos, and logos are essential in modern leadership.

How power changes people

A key element is the “metamorphic effect,” where both parties — leaders and teams — are transformed by the use of power. For example, leaders who frequently use coercion may begin to distrust their people, assuming compliance is due solely to their power rather than genuine alignment. This creates a destructive cycle where they become more reliant on coercive tactics, further alienating their teams. There is a significant difference in impact between creative vs controlling leaders.

How is power created

Gareth Morgan's analysis of the sources of power focuses on where it comes from in an organizational context, while French and Raven's types focus on how leaders exercise it in different contexts.

Bolman and Deal's four frames model and in particular their political frame of leadership is another effective method to understand the different perspectives.

Leaders can significantly expand their influence using these complementary approaches.

Reflection questions for leaders

- What types of power do I have? List your current roles and responsibilities, identifying the types associated with each.

- How adept am I in these power types? Rate yourself on a scale of 1-10 for each and identify improvement areas.

- Do I use them all or rely more on one? Keep a journal for a week, noting which types of power you use in various situations.

- Am I happy with my teams’ responses? Conduct feedback surveys or 1-on-1 conversations to gauge team perceptions.

- What types of power should I work to accumulate? Create a development plan focusing on areas to build more power and influence.

The French and Raven model of power bases provides a fundamental framework for understanding influence dynamics. The most successful leaders balance and adapt their use of power, considering short-term compliance and long-term relationship building.

How will you use your understanding of power to become a more effective leader?

Related reading

- Frances Frei’s trust triangle in organizations

- Using the Johari Window to detect leadership blindspots

- Keats’ negative capability and leadership

- Why Netflix leads with context not control

Sources

- French, J. R. P., Jr., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power.

- Raven, B. H. (1993). The bases of power: Origins and recent developments.

- Goethals, G. R., Sorenson, G. J., & Burns, J. M. (Eds.). (2004). Encyclopedia of leadership (Vol. 1).

- Handy, C. B. (1993). Understanding organizations.

- Johnson, C. E., & Hackman, M. Z. (2018). Leadership: A communication perspective.

- Goethals, G. R., & Sorenson, G. J. (Eds.). (2006). The quest for a general theory of leadership.