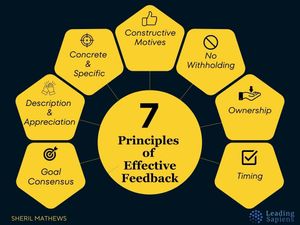

Most managers suck at giving effective, constructive feedback. Equally, most of us are bad at receiving and processing constructive feedback. This is a lost opportunity for everyone.

Edgar Schein, professor emeritus at MIT, was one of the foremost experts in organizational behavior and interpersonal interactions. He articulated a set of principles required to make the process of constructive feedback actually useful.

Many of the commonly found frameworks today have their origins in Schein’s ideas. This post looks at constructive feedback using Schein's framework.

Principle 1: Goal consensus

“The Giver and Receiver Must Have Consensus on the Receiver's Goals. “

Feedback always happens within the context of a given goal. Its function is to show someone where they’re relative to a target so they can make adjustments.

Managers often make the mistake of assuming the context as a given. But without agreement on goals, the feedback lacks context. Or worse, the context is assumed, which also means differing interpretations of the given feedback.

Effective, constructive feedback requires prior mutual understanding on goals to be achieved & performance standards to be met. Without this, feedback can be misconstrued as irrelevant, or even interference.

Example

...it does me very little good to have my tennis instructor point out the flaws in my backhand when my goal was to improve my footwork. A good coach will typically ask the trainee "What do you want to work on today?" before launching into corrective feedback.

…. If I feel that I have some crucial feedback to give, I must first broach the question of where the conversation is headed and what the client is trying to achieve. Only if my feedback fits into that scenario should I feel free to offer it.

Principle 2: Description and appreciation

“The Giver Should Emphasize Description and Appreciation.”

Schein identifies three types of constructive feedback:

- Positive (when person does well)

- This is the easiest to learn from and evokes positive response.

- It focuses on whats’ already working.

- Feeds into our need for maintaining high self-esteem.

- Descriptive neutral

- Often necessary when person is extremely defensive and easily offended.

- Focuses exclusively on description of changeable behavior.

- The description acts as a comparison against agreed standards.

- Negative (where person didn’t do well)

- Hardest to do because it triggers defensive reactions or worse simply dismissed or rejected.

- A negative focus also doesn’t give direction on positive action. It’s more about stopping something and can distract from what’s actually needed.

Many managers rely exclusively on negative feedback as a basis for “correction” and “improvement”. In fact, common understanding of “constructive” feedback is primarily negative.

But we benefit equally from positive feedback that identifies and emphasizes strengths.

The “feedback sandwich” — that tries to strike a balance — ends up being a shit sandwich because managers forget that positives should outweigh the negatives. Often it’s the opposite because the negatives get noticed and flagged much more readily.

In effect, the positives are used to “hide” the negatives. This makes the process easy for the managers, but they lose credibility and trust, thus missing the whole point.

A “rough” delivery of reality combined with trust is much better than a “slick” delivery that happens in the absence, and often to make up for a lack of, trust.

Principle 3: Semantic specificity

“The Giver Should Be Concrete and Specific.“

Lack of clarity, and semantic confusion — no mutual understanding of terms — derails feedback even when done with genuine intent. The key then to effective feedback is semantic specificity.

More general the feedback, more likely it will be misunderstood. More specific it is on mutual observations and actual behavior, less likely it will be misunderstood.

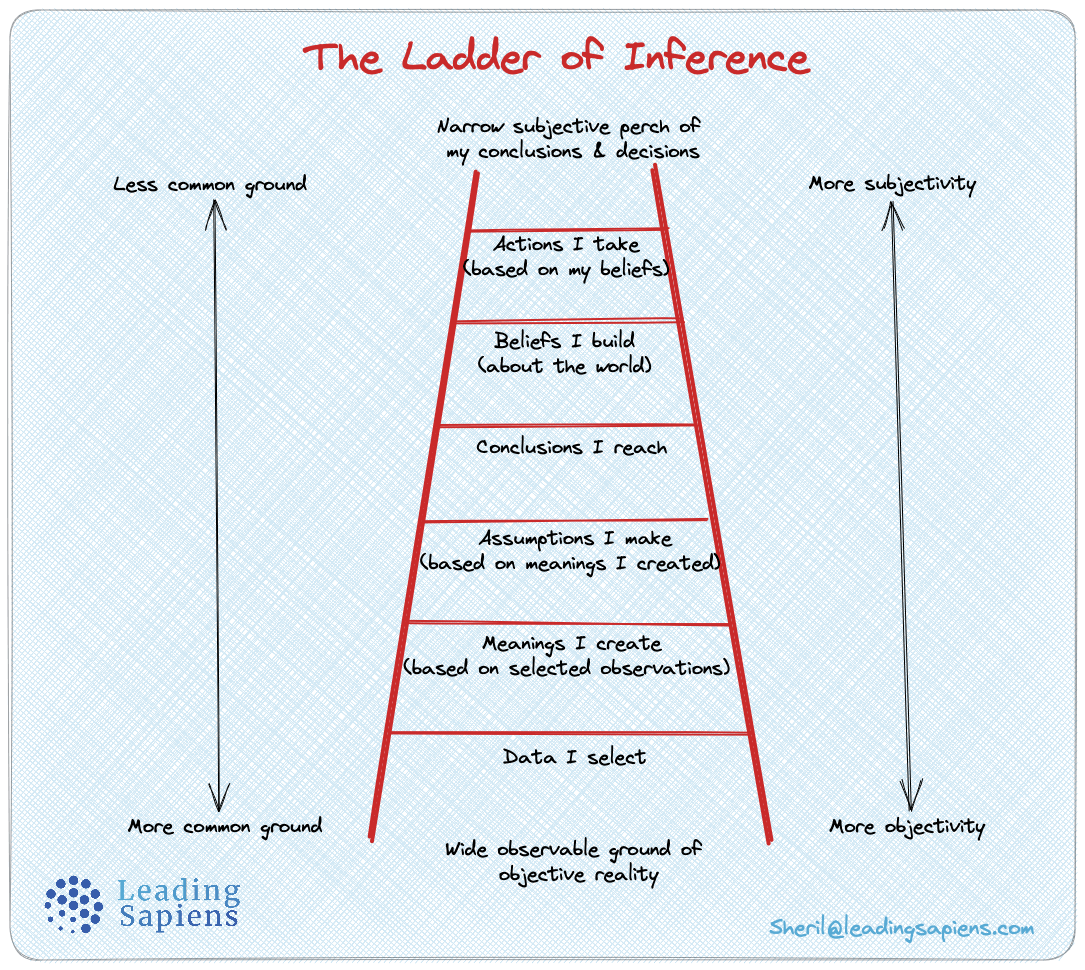

In the context of the ladder of inference model, this means sticking to observable, recordable reality when delivering feedback.

Example

"You are too aggressive" (negative, vague, general)

vs.

“I have observed you shouting other people down when they are trying to express their own views" (descriptive, precise, specific).

"You don't handle your people well" (negative, general)

vs.

"You don't involve your subordinates in making decisions, and you don't give them a chance to express their own views" (negative, specific)

or

"l have noticed that your people are more productive when you involve them in decisions and listen to their points-of-view” (positive, specific).

Principle 4: Trust

“Both Giver and Receiver Must Have Constructive Motives.”

If receiver thinks feedback is only in the giver’s self-interest, they simply won’t be receptive. The recipient has to believe that the giver is genuinely interested in actually helping them. Why should I listen to my manager if I don’t trust his intent?

This is equally applicable to the receiver’s motives as well. Without it, there’s no incentive for the giver to give genuine feedback. Why should the manager give good feedback if she doesn’t think I’ll actually listen?

At its core, we need a baseline amount of trust in each other’s motives. Techniques and tactics simply won’t work without the requisite amount of trust.

Furthermore, trust is easier to develop when both parties are further down the ladder of inference where there’s more objective “observable reality” as opposed to higher up on it where there’s a more judgements and far more subjective.

Example

"I could get you only a 2 percent raise this year because things are generally lean in the company"

(the boss is trying to be truthful but is vague; the subordinate may conclude that he is being subtly told that he is only an average performer and become demoralized)

vs.

"Your performance overall was excellent this last year, and I wish I could reward it with money, but the company has had a generally lean year, so no one got more than a 2 percent raise "

(the boss is being specific, puts the subordinate performance into the proper context, and expresses appreciation).

Principle 5: Transparency

“Don't Withhold Negative Feedback If It Is Relevant.”

We are naturally wired to avoid being overtly critical and to also avoid any criticism because it triggers defensiveness and unpleasant reactions. But this is simply not an option in leadership roles.

Managers who hold back on negative feedback do everyone a disservice, at the very least to themselves.

...if the boss really has a negative evaluation that influences her handling of the subordinate, she is putting the subordinate into a position of having to guess why there have been no promotions, good raises, or good assignments for him.

Most of us withhold negative feedback, and don’t like to hear it because we’re programmed by social norms to avoid it. We don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings, neither do we want to feel uncomfortable ourselves.

Except in careers, that’s often exactly what’s needed to make real progress and avoid blindspots that derail careers.

When giving negative feedback, the key is focusing on changeable behaviors instead of generalized universal statements.

If the giver of feedback criticizes my traits or personality, my self-image and self-esteem become involved, and I cannot readily change general parts of my personality. Hence I will resist or deny the criticism.

On the other hand, if the negative feedback deals with some concrete behavior that both the giver and receiver have witnessed, the giver can express his own feelings about the behavior and his evaluation of it, and the receiver can avoid ego involvement.

Principle 6: Sharing emotions, owning opinions, and avoiding generalities

“The Giver Should Own His Observations, Feelings, and Judgments. “

There are two aspects to this principle. (1) Owning emotions and (2) emphasizing that it’s the giver’s take

Sharing and owning emotions

The giver has to share and own their emotions. This is perhaps the subtlest of points in the framework :

...feedback of the emotional reaction is more likely to be accepted than feedback of the judgment. Saying that your behavior made me angry, anxious, or discouraged is more likely to be heard than the judgment that your behavior was inappropriate or "bad."

The same logic applies for positive feedback. Saying that some of your behavior delighted me or made me proud is far more valuable to the learning process than just saying "You did a good job."

Avoiding generalizations and emphasizing owner’s role

The giver has to emphasize that it is THEIR take and not a universal one. E.g. “You are no good” vs ”I think you are no good”. The first is a universal generalization that sounds like a final judgment that cannot be challenged or explored. In the second, giver makes explicit their ownership of the feedback.

It is important for the giver to own the feedback in order to make it discussible and a source of potential learning. Impersonal generalities are demeaning because they remove the rationalization that it may be just the giver's idiosyncratic reaction.

…A general judgment also implies that it has been tested with others and is a final conclusion rather than the giver's immediate reaction.

Principle 7: Timing

“Feedback Should Be Timed to When the Receiver and Giver Are Ready.“

Four aspects make for good timing in constructive feedback:

a. Readiness of receiver

This is most critical as without it everything else is moot. A receptive learner can overcome a lack of skill on the giver’s part. However, no amount of skill can make up for a lack of receptivity. Thus receiver’s motivation to learn is crucial.

b. Readiness of giver

The giver has to be ready as well. This comes from thinking through & ensuring it doesn’t violate any of the principles. And of course care, aka giving a damn. Needing some time also means that as receivers, it’s good to give stakeholders time to process feedback instead of asking for it impromptu.

c. Setting the stage/context

How feedback gets interpreted depends on the context within which it happens. Goal consensus is part of it, but this is equally applicable at the individual interaction level. Without a context for the conversation, your message can be easily misconstrued.

- More on context:Importance of mastering context in leadership

- More on different types of conversations: Closure conversations

d. Time and space

Closer the feedback is to relevant events, the more likely everyone remembers specific details. Too far and we forget the details. Too soon and we might not have had enough time to process it.

Related reading

- Why is accurate feedback so elusive and why is it exceptionally hard to give and receive? Schein articulated 4 parts of the self based on the Johari Window model and the different patterns of communication that this creates. Between these two he captures the many pitfalls of communication that impedes accurate feedback. Awareness of these different parts of our self and the resulting communication patterns can dramatically improve effectiveness in how we interact with others.

- Development in leadership is mainly an inside job.

- Leadership can’t be taught but can be learned.

- The Ladder of Inference:

Sources

- Process Consultation Revisited by Edgar H. Schein

- Humble Inquiry by Edgar H. Schein