Leaders today face complex challenges that can't be solved through skill development alone. Jack Mezirow's transformative learning framework, developed through three decades of research, is a useful tool to help leaders shift how they think and make meaning of their roles. In this piece, I explore Mezirow's transformative learning theory and how it’s used in leadership coaching.

First off, why bother? The reality is that most leaders don't need any more information. What they need is better ways to make sense of what they already know — what I call leadership sensemaking.

Two people in the same meeting can leave with entirely different interpretations of what happened and what to do next. The difference isn't in what they see — it's in the invisible filters that determine how they're seeing.

This is where leadership development often misses the mark. It gives leaders new techniques —adding more content to their mental library — but rarely examines how they think and make meaning. It's the difference between giving someone a new map and helping them understand how they've been reading maps all along.

I've structured this article around key terminology from Mezirow's Transformative Learning theory:

- (1) Frames of Meaning

- (2) Disorienting dilemmas

- (3) Critical reflection

- (4) Reflective discourse

- (5) Reflective action

- Leadership coaching as a vehicle for transformation

Throughout, I discuss their use in the leadership coaching process. I close the piece by showing how coaching is an apt vehicle for enabling transformation.

Let's jump in.

(1) Frames of Meaning

To understand how coaching works as a vehicle for transformation, we must first understand how we make sense of our world. Mezirow called these meaning structures: the hidden scaffolding behind judgments, decisions, and reactions.

In leadership, the mental models that create success at one level become constraints at the next. The detailed analysis that made you an effective director creates decision paralysis as a VP. The control that worked with a team of five becomes micromanagement with fifty.

It’s a structural problem, not a skills problem. You have the right tools but you’re working from the wrong blueprint.

Meaning structures operate at three levels, from surface to depth:

- Points of view are immediate judgments and assumptions that feel like facts: "My manager is skeptical of my suggestions." "This team resists accountability." These are easier to examine because they're closer to conscious awareness.

- Habits of mind are deeper thinking patterns inherited from culture, upbringing, and experience: "I need the right answer before I speak." "Strong leaders don't show vulnerability." These unconscious predispositions shape our interpretations, but most don't realize it.

- Frames of reference are the deepest structures — the invisible filters that determine what counts as relevant information in the first place. E.g. they decide what you notice in a meeting and what you dismiss entirely.

In coaching, the work often begins by surfacing these frames. Leaders may come with well-formed questions, but beneath those goals are filters they're unaware of. Coaching reveals the structure behind the structure: not just how you're acting, but why certain possibilities don't even show up as options.

Conventional leadership development focuses on skills or behavior. But behavior follows interpretation, and interpretation is shaped by meaning structures. Coaching that respects this architecture doesn't rush to advise or direct. It stays with the interpretation and creates space to examine the lens, not just the problem.

This is slow work. But it's what distinguishes temporary improvement from lasting transformation. Once a frame of reference shifts, everything downstream changes.

(2) Disorienting dilemmas

If meaning structures are the architecture of sensemaking, what causes someone to consider renovating the structure?

Mezirow called these disorienting dilemmas: experiences that don't fit the existing map. Something that cracks the logic of your current frame of reference. It's not only uncomfortable; it's existentially confusing. You can't make sense of it, or go back to how things were.

These are entry points into transformation because they're destabilizing. In leadership, disorienting dilemmas are common and inherent to the role:

- You're promoted into a job you don't feel ready for.

- A once-successful strategy stops working.

- You're forced to make decisions with no clear "right" answers.

- Feedback reveals an unknown blind spot.

These situations are potent because they violate your assumptions. You thought you knew how leadership worked, or that you were good at something. Suddenly, the internal model doesn't hold.

This isn't a tactical failure; it's a failure of your meaning structure. It's inadequate.

Meaninglessness as signal

Mezirow described disorienting dilemmas as events that create "a patch of meaninglessness." What triggers transformation is the inability to make sense of it.

This matters because in most professional cultures, disorientation is seen as a problem to quickly solve or avoid. But from a developmental lens, they're invitations; evidence that your current meaning structure is too small for the world you inhabit.

Instead of prematurely reassuring or problem-solving, leadership coaching helps you stay with the discomfort long enough to extract something from it.

Edge emotions

Disorienting dilemmas trigger what researchers call edge-emotions: shame, fear, anger, confusion, grief, and despair. While they feel dangerous, they're essential. They "offer access to knowledge we could not perceive from our existing meaning perspectives." [4]

In other words, these emotions are not noise, but data. They mark the boundaries of our current frame of reference and are often the only path to something new.

Coaching that avoids these emotions or rushes to regulate them misses the point. The task is not to eliminate discomfort but to metabolize it. To sit at the edge long enough for something else to emerge.

Leaders facing disorienting dilemmas often can't articulate the problem. They just know something feels off. A skilled coach doesn't rush to clarity. They help the leader notice what no longer fits, ask questions to surface underlying assumptions, and scaffold a new, coherent frame of meaning.

In practice, this means:

- Naming the disorientation instead of fixing it.

- Exploring emotions the leader would typically bypass.

- Identifying ineffective long-held beliefs.

- Recognizing that ambiguity signifies growth, not weakness.

This work isn't always clean or linear. But it allows you to update meaning structures instead of merely surface-level tactics.

(3) Critical reflection

Once a disorienting dilemma has fractured the old meaning structure, the real work begins by asking: What was I standing on before it broke?

This is critical reflection, and the centerpiece of adult development. Without reflection in leadership, discomfort becomes disorientation without growth. With it, discomfort fuels transformation.

But not all reflection is created equal.

Three levels of reflection

Mezirow distinguishes three types of reflection, and only one restructures meaning.

(1) Content Reflection. Focuses on the what. What happened? What do I believe? What do I need to do? This is tactical problem-solving. It's the go-to mode for most professionals: analyzing situations, updating knowledge, troubleshooting issues.

(2) Process Reflection. Focuses on the how. How did I make that decision? How do I approach this type of situation? This level starts to get under the hood of habits and routines. It examines patterns of thinking and acting and opens the door to behavioral change.

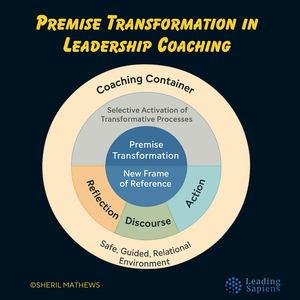

(3) Premise Reflection. Focuses on the why. Why do I see it this way? What assumptions underlie my beliefs? What criteria am I using to evaluate this? This is the deepest level. It interrogates the frame through which we interpret reality. It questions the logic, values, and rules governing perception and judgment. This reflection reorganizes your internal operating system.

Only premise reflection leads to Mezirow's transformation of meaning perspective. The others may tweak or refine, but do not fundamentally reshape. Note the parallel to double-loop learning.

Organizations block premise reflection

In modern workplaces, premise reflection is rare, not due to leaders' incapability, but because the environment disincentivizes it.

Work cultures systematically prevent premise reflection. Quarterly earnings calls don't pause for existential inquiry. Leaders who say "I need to examine my assumptions about this market" may get nervous looks from the board.

This creates what we might call "premise avoidance": an organizational bias toward content and process reflection because they feel safer and more controllable. The deeper the reflection, the more it threatens existing power structures and certainties.

Time pressures reward fast, tactical fixes (content reflection). Cultures that fetishize best practices often substitute technique for thinking (process reflection).

Ironically, the more senior the leader, the harder it is to find safe ground for premise reflection. Questioning deeply held assumptions can feel destabilizing, especially when your role is to project clarity and certainty. Their identity is often fused with the very ones that need to be challenged.

That's where leadership coaching becomes essential.

Leadership coaching and premise reflection

Coaching helps leaders to reflect at the right level. This means slowing down the urge to fix, and instead identify the underlying pattern:

- "What belief did you have going in?"

- "What feels familiar?"

- "What are your assumptions about success here?"

- "Whose voice is this in your head?"

These are designed to probe beneath the behavior and into the assumptions — implicit, inherited, or outdated — driving it.

This work can be disorienting. Leaders often discover they're operating from mental models they never consciously chose. The things that brought them past success — hyper-control, constant availability, and self-reliance — are now undermining them.

What emerges is not just self-awareness, but what Mezirow called subjective reframing: the capacity to re-see one's narrative from a place of informed distance.

This separates leadership coaching from advice-giving or mentorship. It's not about telling you what to do differently, but helping you see and choose differently.

Premise reflection can be emotionally taxing, surfacing regret, embarrassment, and grief. Leaders might realize they've made key decisions out of fear or followed outdated scripts from early authority figures or past roles. But the cost of not reflecting is higher: stuck patterns, repeated failures, and derailment.

Coaching creates a protected space — a reflective container — for this work. A place where leaders don't have to perform, impress, or justify; where they can dismantle old assumptions and build something more sturdy and context-relevant.

(4) Reflective discourse

Transformation doesn't happen in isolation; leaders must test their new sensemaking with others. But most organizational conversations make this impossible.

The dialogue dilemma

Leaders need honest dialogue to test evolving perspectives, but their role requires projecting certainty. Most workplace conversations focus on performance or persuasion, not genuine inquiry. Even feedback sessions mask judgment behind openness.

The higher you rise, the fewer people will challenge your thinking. Everyone has an agenda, a hierarchy to navigate, or a relationship to protect. The conversations leaders need most — where they can express uncertainty and test assumptions — become the riskiest.

Coaching as dialogue laboratory

Leadership coaching creates "reflective discourse": a space to bring uncertainty without consequence. Here "I don't know" isn't a liability but the start of discovery.

Your coach is a "discourse partner": someone who challenges without threat, listens without judgment, and reflects inconsistencies to sharpen awareness:

- You value collaboration, but just described your team's input as 'a distraction.' Help me reconcile that.

- You're confident in your plan, but seem uneasy. What's beneath the certainty?

- What if you’re wrong about that stakeholder?

The coaching dialogue is a rehearsal space where new perspectives are formed, tested, and integrated before being enacted in the real world of consequences and performance.

(5) Reflective action

Transformation is incomplete until it manifests in the real world. A mindset shift, no matter how profound, is only theoretical until it changes your actions, decisions, and relationships. In Mezirow's framework, this final step is reflective action, where new meaning translates into meaningful conduct.

But not all action is reflective. Much of what leaders call "taking action" just reinforces old frames, executing the same logic with new energy. Reflective action, by contrast, requires reexamining the underlying assumptions driving behaviors.

The action paradox

Leaders facing a disorienting dilemma confront an impossible choice: act quickly on incomplete understanding, or pause for deeper reflection while external pressure mounts. Traditional leadership advice says "be decisive." Transformative learning says "stay with the confusion until clarity emerges."

The resolution isn't choosing one or the other. Rather, it's developing the capacity to act from conscious uncertainty rather than false certainty. This is what separates effective leaders from merely competent ones.

From insight to integration

The hallmark of reflective action is congruence. After a disorienting dilemma and deep reflection, leaders see what needs to change, why it matters, and how it fits with a more honest understanding of themselves and their context.

- A manager who used to over-control team dynamics may start delegating because they've re-examined their assumptions about trust and control.

- A high-performing exec might say "I don't know" more often because they now see ambiguity as part of their role, not a threat to their identity.

- Another leader might slow down execution because they've reframed their view of success from quick wins to long-term system health.

Each shift is a deeper premise transformation. They aren’t just acting differently, but doing it from a different place altogether.

Action is the final test of meaning

Mezirow argues that transformation is about acting from a frame that is more coherent, inclusive, and aligned with reality.

In leadership, this means not just adapting to complexity, but inhabiting it. Acting in ways that acknowledge ambiguity, invite multiple perspectives, and reflect a grounded sense of self.

This is the paradox of reflective action: it's outwardly pragmatic but inwardly profound. A small behavioral tweak may signal a tectonic shift underneath, reshaping how you think, feel, and make meaning in the world.

Leadership coaching as a vehicle for transformation

It's tempting to view learning as content: What did I learn? What tools did I acquire? But when the real task is to rethink fundamental assumptions, the container matters as much as the content.

The coaching relationship provides just that: structured yet flexible, personal yet performance-oriented.

Let’s consider the ways coaching enables Mezirow’s vision of transformation.

(a) Coaching targets mental models, not just behaviors

Transformative learning requires modifying meaning structures, habits of mind, and points of view. Traditional leadership development aims to add tools. Good coaching doesn't just add. Instead, it edits, refines, and discards mental models that are no longer working.

The shift is subtle but crucial: Instead of "What should I do?" you ask, "What am I assuming?" or "How am I framing this?" Coaching operates at the level of assumptions.

(b) Coaching supports the emotional labor of change

Changing your premises is not only an intellectual task, but also an emotional reckoning. Premise reflection can challenge deeply held views of self and others. Mezirow calls it "an intensely threatening emotional experience."

That's especially true in leadership, where frames are tied to identity: Am I competent and respected? Am I really in control? Coaching is the secure base where leaders can stay in the discomfort of ambiguity without rushing to a solution.

(c) Coaching enables autonomy

The end goal isn't just a more capable leader, but a more autonomous one. Mezirow is clear: the goal of transformative learning is to create self-authorship; defining your own values, purposes, and beliefs, instead of adopting them uncritically. Coaching supports this by:

- Helping identify outdated assumptions.

- Creating space for new, honest, relevant, and grounded interpretations.

- Reinforcing a sense of agency, not just competence.

This is vital in ambiguous environments. Self-directed leaders don't have the "right" answers but know how to interrogate the frame behind the question.

(d) Coaching makes change sticky

Leadership coaching helps translate new understanding into sustained behavior in several ways:

- Designing experiments. Instead of vague commitments ("I'll listen more"), the coach helps the leader define specific, testable behaviors ("I'll ask two open-ended questions before offering an opinion in our next team meeting").

- Anticipating friction. The coach surfaces the internal and external resistance during change, including the pull of the old self, skepticism of others, and the temptation to revert under stress.

- Naming regressions without judgment. When leaders inevitably backslide, the coach reframes failure as simply data that shows which parts of the old frame still exert influence and where the new one needs reinforcement.

- Building self-efficacy. Through guided reflection on what works and why, leaders internalize the new frame as a new capacity.

This process is powerful because it occurs in real-time with real challenges. Over time, this cycle of insight, enactment, and reflection builds self-directed competence.

Leadership coaching works not because it gives advice, but because it enables meaning reconstruction and premise transformation. It meets leaders at the boundary of their knowledge and helps them build a bridge toward who they want to become.

That bridge is built through challenge, safety, reflection, dialogue, and action. Coaching makes the invisible architecture of transformation visible and walkable.

Sources and References

- Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative dimensions in adult learning.

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning to Think Like an Adult.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational Learning.

- Eschenbacher, S., & Fleming, T. (2020). Transformative Dimensions of Lifelong Learning: Mezirow, Dewey, and the Quest for Transformation. Journal of Transformative Education.

- Johnson-Bailey, J. (2010). Transformative Learning. In C. E. Kasworm, A. D. Rose, & J. M. Ross-Gordon (Eds.), Handbook of Adult and Continuing Education.

- Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to Change.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner.

- Sherlock, B. (2004). Transformative Learning Theory: A Perspective from Practice. Studies in the Education of Adults.