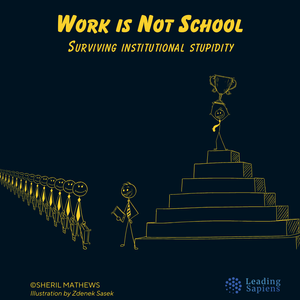

For 16+ years, we master the rules of school. Study hard, get good grades, follow the formula and ultimately merit wins. Then we enter the workforce and none of it works quite like we thought. This becomes painfully obvious as you rise higher in the org.

Even seasoned veterans forget this. Recently, a director-level client hit a minor career bump and spiraled into crisis mode, their expectations still anchored in what I call "school rules".

Organizations don't run purely on merit or even clear criteria. Although they claim otherwise using buzzwords like “merit” and “data”. That’s only one part of the story, and also what’s visible.

The other part, often more consequential, runs on flawed psychology, imperfect decisions, and competing interests. You can call it organizational absurdities. Or more bluntly, institutional stupidity.

What follows is a reality check. It’s a “letter to frustrated high-performers” who keep bumping up against these unwritten rules of work. Consider it your guide to staying sane while playing the long game.

- If you have to, blame stupidity not malice

- Organizations are anything but meritocracies

- Perception matters as much as performance

- Don’t waste time fighting for “objective fairness.”

- Positioning what you offer

- Mind the gap: your standards vs their’s

- Higher you go, more it’s an inverted funnel

- Know which game you’re choosing to play

- Watching your circle of control

- Keep a balanced portfolio

If you have to, blame stupidity not malice

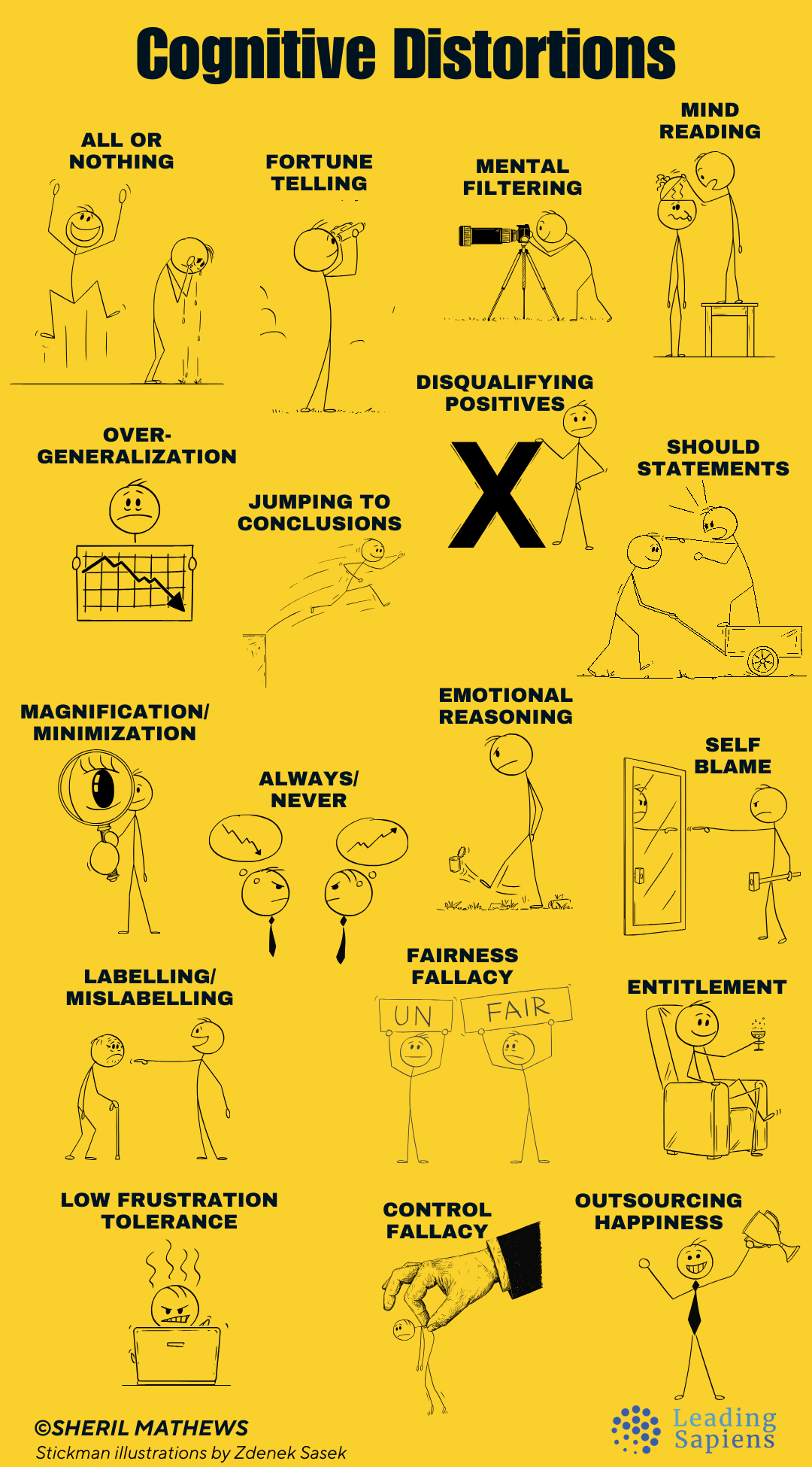

Most of what we chalk up to “politics” or “backstabbing”, aka bad intent, is often better explained by stupidity, inertia, bad incentives, fragmented attention, and misaligned maps of reality.

People are juggling too much, thinking too little, and rarely stepping back to ask, “What actually makes sense here?”

When you assume stupidity instead of malice, you stay above the fray, stop taking slights personally, or turning misjudgments into betrayals. This way we retain agency and choice.

Assuming malice turns you into a cynic. In contrast, assuming stupidity keeps you curious. Instead of fighting ghosts, you study the system and ask better questions:

- What pressures is that person responding to?

- What game are they trying to win?

- What am I assuming as rational that’s not?

No one is out to get you; they’re just out to get through the week. The shift from malice to stupidity gives you just enough distance to be curious instead of reactive.

Organizations are anything but meritocracies

Managers will claim they are, and we want to believe them. But the reality is that the best don’t always rise. At least not as easily or automatically as we think they should.

Sometimes they do. But often, what gets rewarded isn’t performance but proximity to power, timing, perception, and political usefulness.

This doesn’t mean performance doesn’t matter. It means performance is necessary but not sufficient. It is the entry ticket that gets you through the door, but does not guarantee a seat at the table.

Assuming that excellence is obvious is the fatal error of the conscientious expert. Although it creates value, performance doesn’t automatically generate visibility, influence, or narrative. And those are the currencies that get traded when decisions are made by humans.

Merit matters, but it needs a stage and a spotlight. It doesn’t mean becoming a shameless self-promoter. Rather, your work needs a distribution strategy.

Perception matters as much as performance

In school, everyone was evaluated against an objective criteria by someone paid to assess fairly.

In organizations, no such thing exists. Instead, perception is the “data”. And this data is constructed often haphazardly by busy people working off limited inputs. You have to manage the story by shaping impressions intentionally.

Not only does perception matter as much as performance but who’s doing the perceiving matters even more.

Not all perceivers are created equal. A peer may love your work but they might not be a critical node in the web of influence. Who gets consulted? Do they know what you’ve built, and have they heard your name in relevant contexts?

It’s not just “do great work.”; it’s also “do the work that’s perceived as valuable.” This means translating your work’s significance up the chain and shape its interpretation. If not, others will do it for you and they may not be generous, or even accurate.

For more, see my last two articles: Schrodinger’s Cat at Work Part I and Schrodinger’s Cat at Work Part II.

Don’t waste time fighting for “objective fairness.”

On paper, organizations love metrics: KPIs, OKRs, dashboards. They create the appearance of detached objectivity.

Meanwhile, subjective decisions are constantly happening behind the scenes. The decisions about who to trust, or who gets a shot are made through informal reputations and shared stories about your value. Then the “data” is used to justify them in retrospect.

Rather than rant against the system, get good at reading the underlying subjective logic:

- Who does this person trust, and why?

- What do they consider strategic vs tactical?

- What would make them feel safe betting on me?

Subjectivity isn’t the enemy. It’s the underlying physics of it.

Positioning what you offer

You may have had the right message but at the wrong moment, or in the wrong wrapper.

Positioning is the context around your contributions: Why now? Why you? Why this way? A good idea, or stellar performance, poorly positioned can seem irrelevant. In contrast, a mediocre one nicely positioned is deemed visionary.

It’s not just what you say but also when, how, and through whom you say it.

Persistence matters as well. Think in campaigns, not just one-time efforts. In my piece on effective conversations I wrote:

It's the series of messages in different forms that over time makes the difference. More akin to waves shaping the shoreline rather than the occasional once in a lifetime tsunami.

What messages are you sending, are they varied, and are you doing it consistently? This is as true for marketing products as it is for positioning yourself inside organizations.

Mind the gap: your standards vs their’s

Another obvious but forgotten reality of organizational life: Not everyone operates by the same playbook.

You prioritize substance and direct contribution, while others focus on visibility and relationship-building in ways that are uncomfortable to you. It’s that colleague who excels at positioning routine work as “strategic”, or the peer who builds influence through cultivating key relationships.

And yes, these approaches do yield results.

But this doesn’t mean dismissing it as pure politics or simply abandoning your principles. It means understanding the landscape you're operating in.

You can’t effectively participate in a game you refuse to see clearly. You're not at a disadvantage because you choose to act with integrity. It’s because you fail to recognize that influence flows through multiple channels and others are willing to play differently.

The key is not to match their behavior but to factor it in. Instead of expecting fairness, anticipate asymmetry. And then get creative about how you play.

Being ethical doesn’t mean being passive but tactically awake.

Higher you go, more it’s an inverted funnel

Perhaps the most obvious point but also easy to forget especially if your career has been on autopilot so far.

There’s a bottleneck up top: fewer seats, more ambiguity, less structure and high subjectivity. It’s not just hard to get in but even harder to stay clear on what “good” even looks like.

This means you can do everything right and still get passed over. That’s not a verdict on your worth or ability, just geometry.

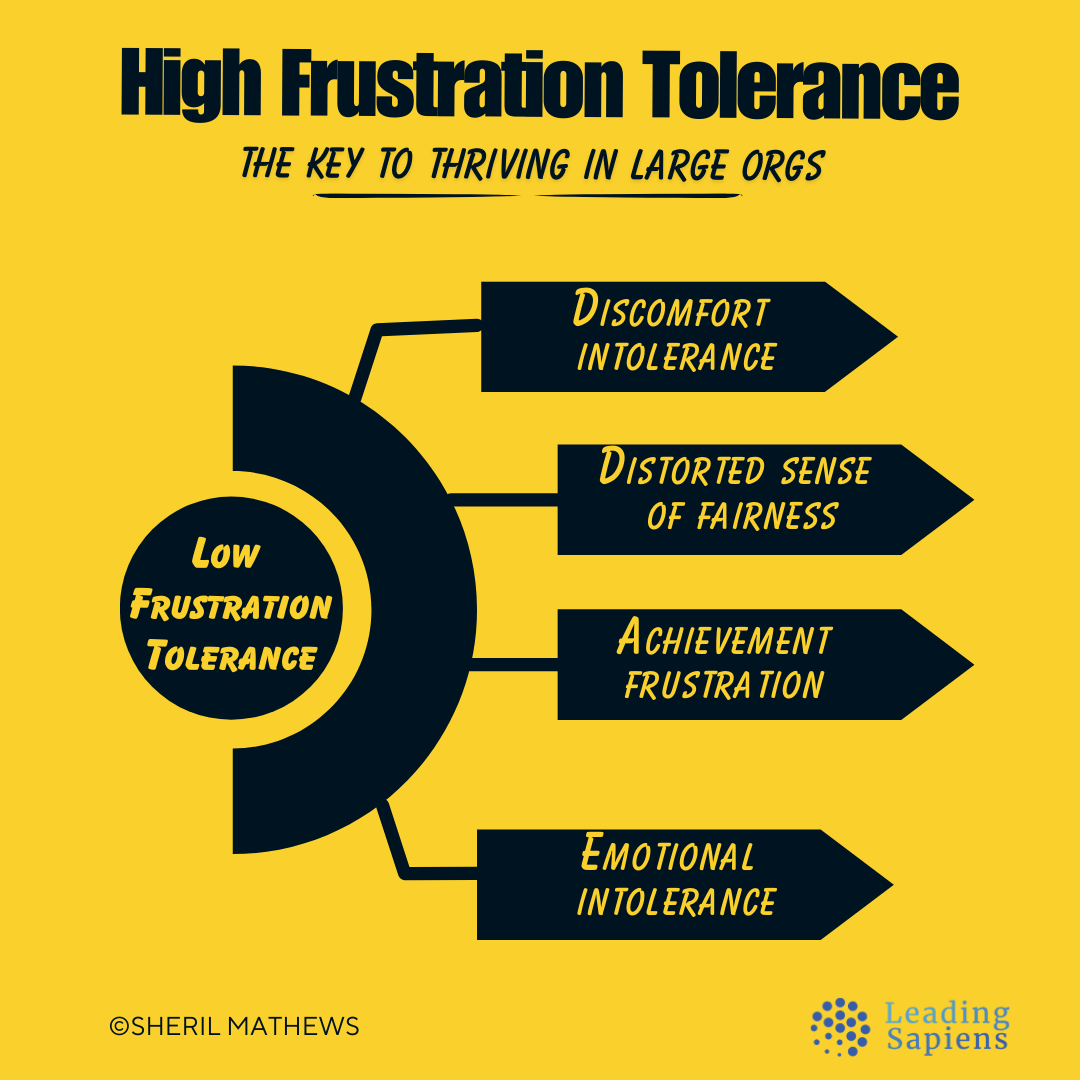

It also means that staying the course when things don’t go your way isn’t just a virtue but a practice. To play the long game, you have to keep showing up even after crushing disappointment without getting cynical of the process. Put differently, you need high levels of frustration tolerance.

Cliched? Yes, very much so, but also uncommon. It means if you can pull it off, it’s a source of power.

Know which game you’re choosing to play

There is no one game being played. There are multiple, overlapping games with different scoring systems. Some are playing to build long-term credibility; others for short-term visibility.

You can’t play them all and neither should you try.

The real problem is we slide into playing someone else's game without realizing it. We adopt the norms and metrics of others without checking if that’s the game we actually want to play, let alone win. So we end up optimizing for a role we don’t respect, or chasing promotions that hollow us out.

Whatever you’re doing, own it outright. Not just the upside but also the downside. If you're focused on building something lasting like developing others, or robust systems, you need to accept that visible status markers (titles, promotions, recognition) might not happen right away.

The danger isn't which path you pick, whether it's chasing promotions or maintaining your autonomy. The real disaster is to sleepwalk down a path while pretending you had no choice in the matter.

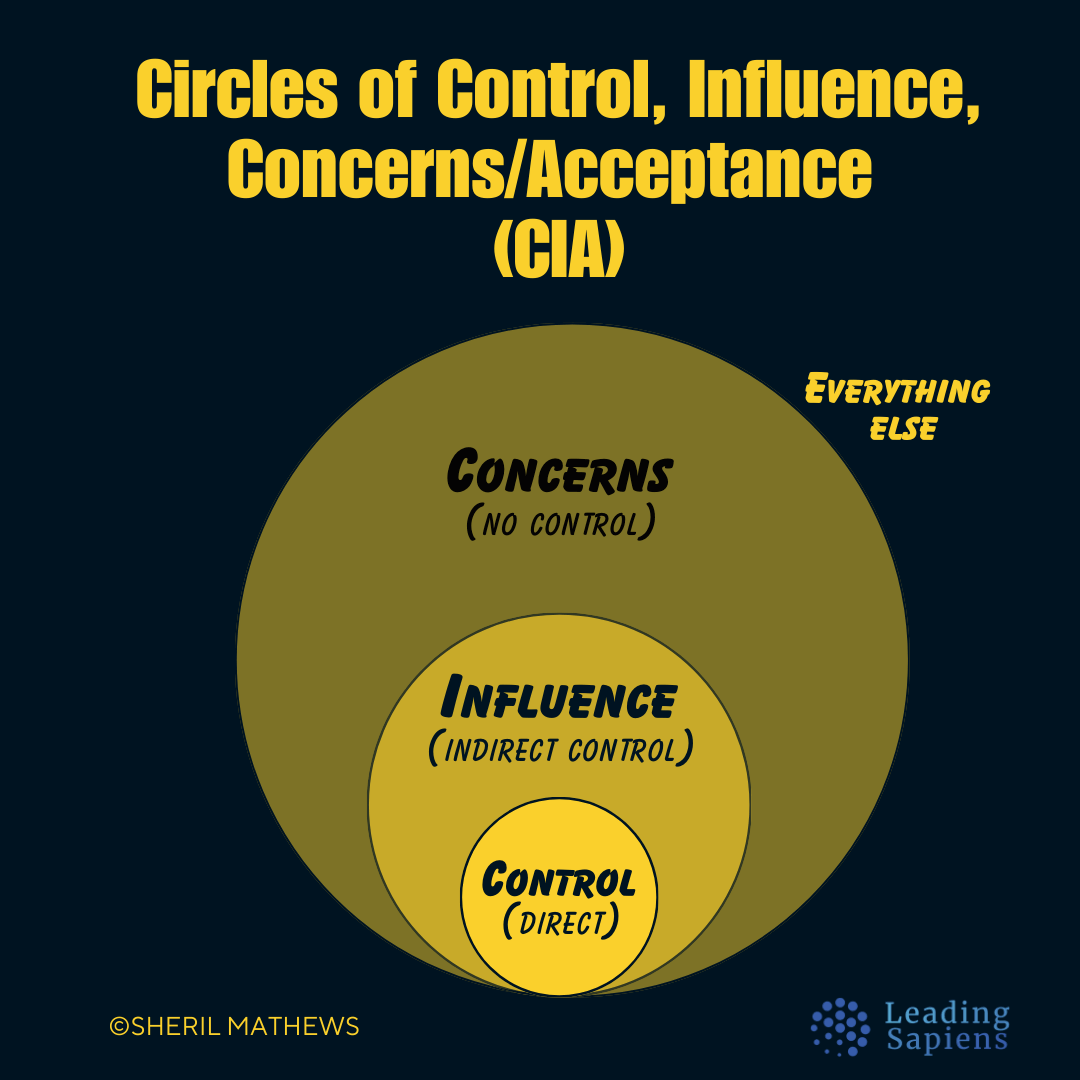

Watching your circle of control

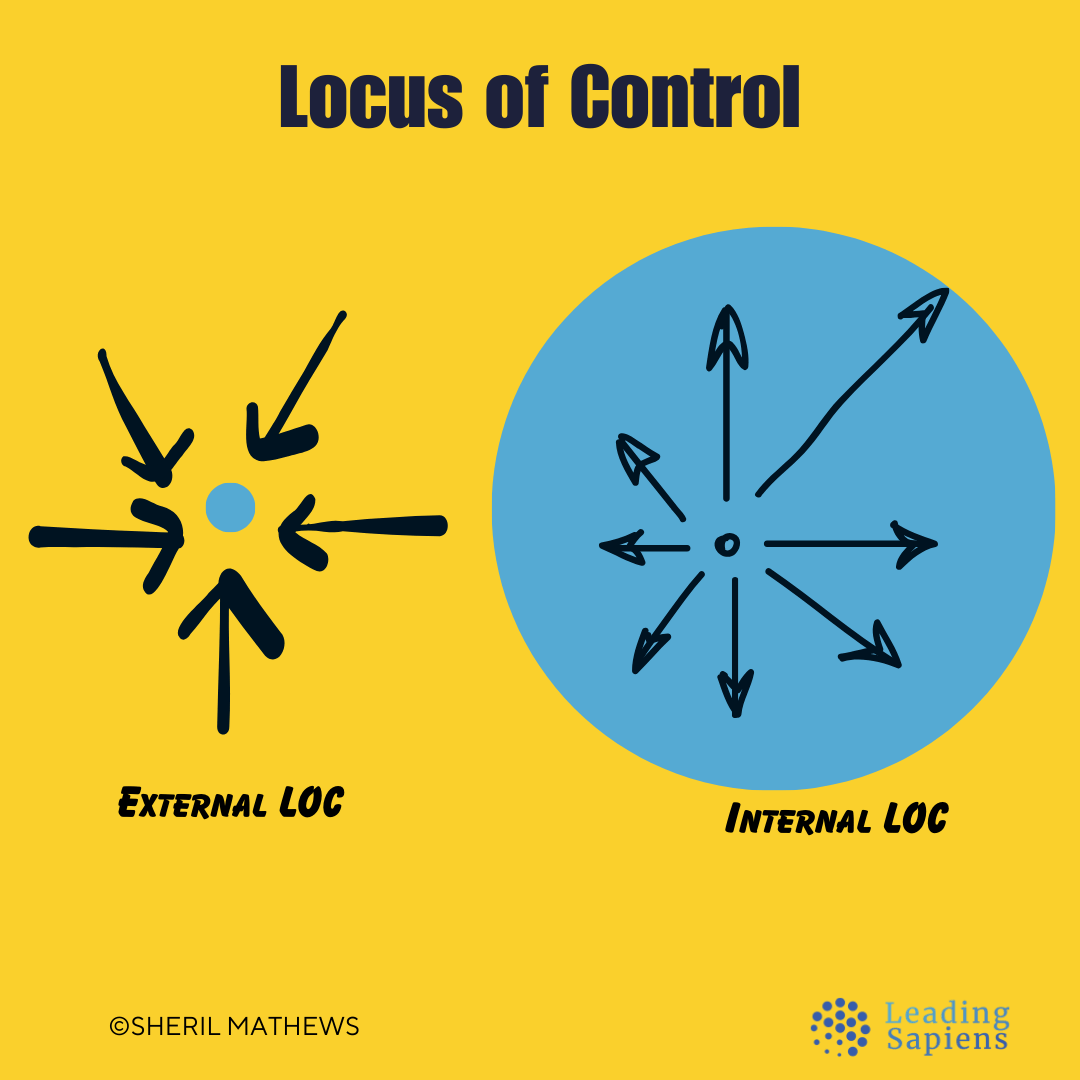

An easy way to burn out is to focus relentlessly on things you care about but cannot actually influence. Over time, especially in large organizations, it's tempting to attribute everything to forces outside yourself. This induces organizational helplessness. A sense that nothing you do matters unless someone above says so.

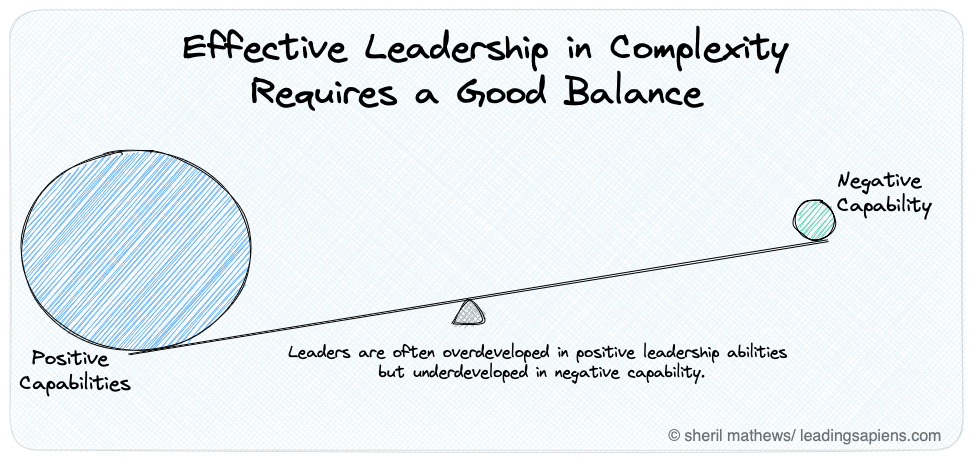

Fight that, not with bluster, but with deliberate ownership of the space you control and influence. While experienced professionals often have more influence than they think, it's distributed differently than they expect.

The key is maintaining an internal locus of control which includes your positioning, relationships, and what you are building.

Keep a balanced portfolio

This is a well-understood concept in investing but often missing in the context of long careers. If all your identity is wrapped up in organizational validation, you're fragile. This means setbacks don't just rattle your job, it rattles your sense of self.

Many mid-career professionals learn this the hard way. To state the obvious: you are not your title, or your most recent performance review.

The anti-dote is diversification not of money, but meaning.

Rebalancing here means investing in other sources of connection and community. This includes:

- Developing a craft that exists beyond a given employer.

- Investing in communities that outlast org charts.

- Projects, relationships, and sources of learning that replenish.

You are building adaptive capacity.

A balanced portfolio also helps to play the long game with more psychological courage because your whole life isn't riding on the next promotion cycle or external validation.

In closing

By recognizing the subjective currents that shape work environments, we can operate within them more skillfully.

This isn't cynicism or gaming the system. Rather, it's developing a nuanced understanding of how organizations actually function. This stance equips us to make more intentional choices about how to engage, contribute, and create meaning.

As ideal as it sounds, the goal isn't to eliminate organizational absurdities, but to work effectively within and around them. By staying in the game, you find ways to gradually improve the system from within.

Organizations are ultimately human constructs. Imperfect, but not immutable.

Related reading