We think effective leaders are great problem-solvers. That’s only partially true. What they’re really good at is multi-frame thinking. They help solve problems by changing how they are framed, operating one level upstream where the real leverage lies.

Multi-frame thinking means deliberately shifting interpretive lenses until you find the one that unlocks action. The frame you choose — consciously or not — determines which solutions you even see. It shapes what gets attention, what gets dismissed, and what feels actionable. Get it wrong, and you solve the wrong problem perfectly. Get it right, and the path forward seems obvious.

In stable environments, default frames work fine. The categories are familiar, the patterns predictable. But in complex situations—where real leadership is required—the frame itself is the decision.

In this piece, I examine why multi-frame thinking is essential in leadership, how it works, and where it can mislead you.

Effective leaders see more not because they’re smarter, but because they’ve trained themselves to shift lenses. They don’t stop at the first explanation that makes sense. They pause, rotate the perspective, and ask what the situation looks like from different angles. In other words, they’re adept at changing frames.

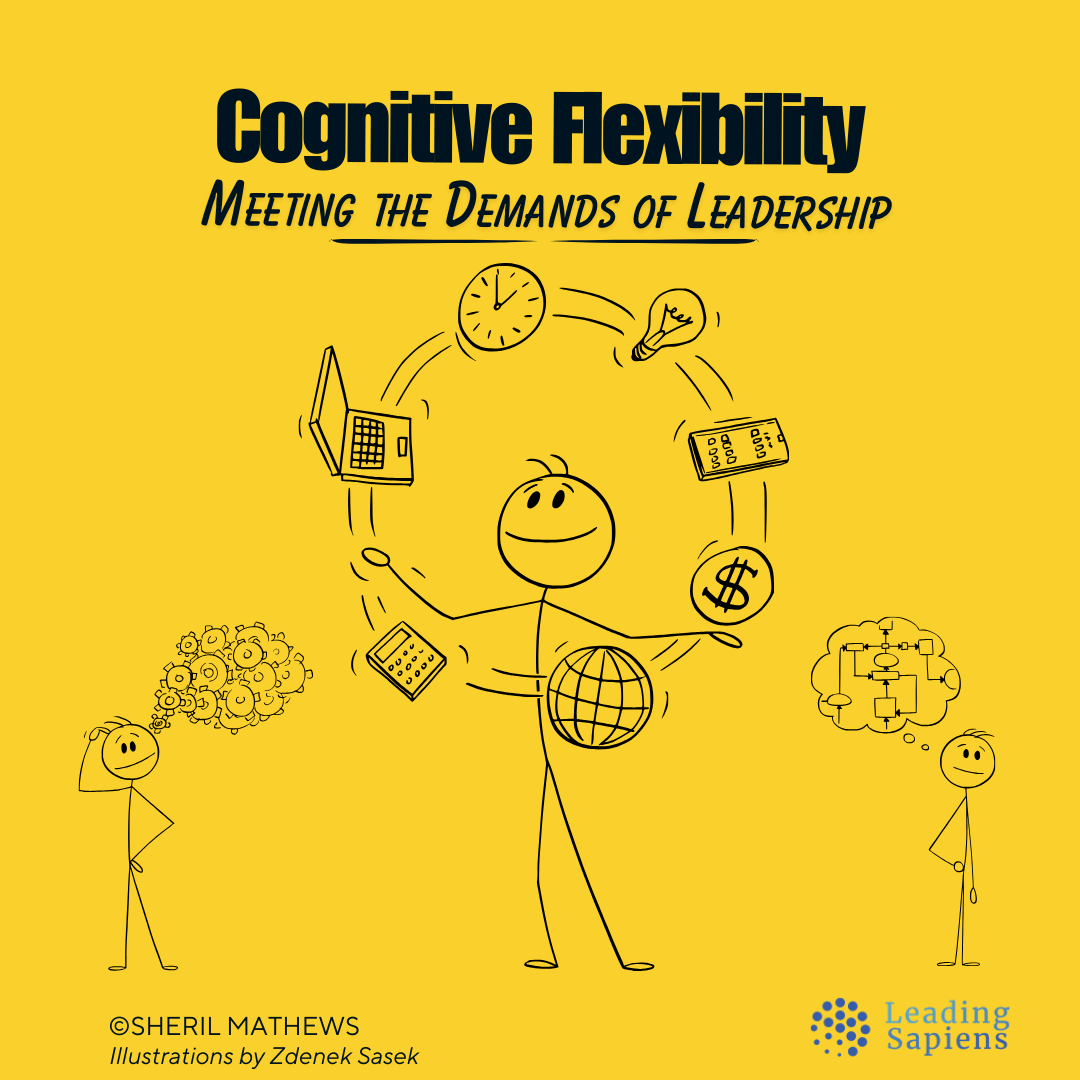

As complexity increases, the real constraint is the ability to interpret what’s happening with enough depth and dimensionality to act wisely.

The challenge is that most professionals aren’t taught to do this. They’re trained in a dominant frame — finance, operations, HR, engineering — and rewarded for pattern recognition within that logic. Over time, their interpretive range narrows.

Multi-frame thinking is one way to undo that narrowing through deliberate contrast. It invites you to ask: What’s the focus? What’s being dismissed? What logic is driving the definition of the problem?

What Are Frames

A frame is the lens through which a situation is understood: what gets foregrounded, what fades into the background, and what doesn't register at all.

You see this filtering effect in meetings all the time. A project misses its targets. One executive blames poor follow-through, another points to unclear accountability, and a third questions the project made strategic sense to begin with. Same data, but completely different interpretations. They're not solving different aspects of the same problem; they're seeing different problems altogether.

Whether you notice them or not, frames are already operating. And unlike tools in a kit, they don't wait to be selected, but are shaping the conversation implicitly. As Donald Schön and Martin Rein write,

Different frames… cause us to notice different facts and make us receptive to different arguments, and there is no frame-neutral basis for choosing among them.

In other words, facts don't speak for themselves. What you see depends on where you're looking from.

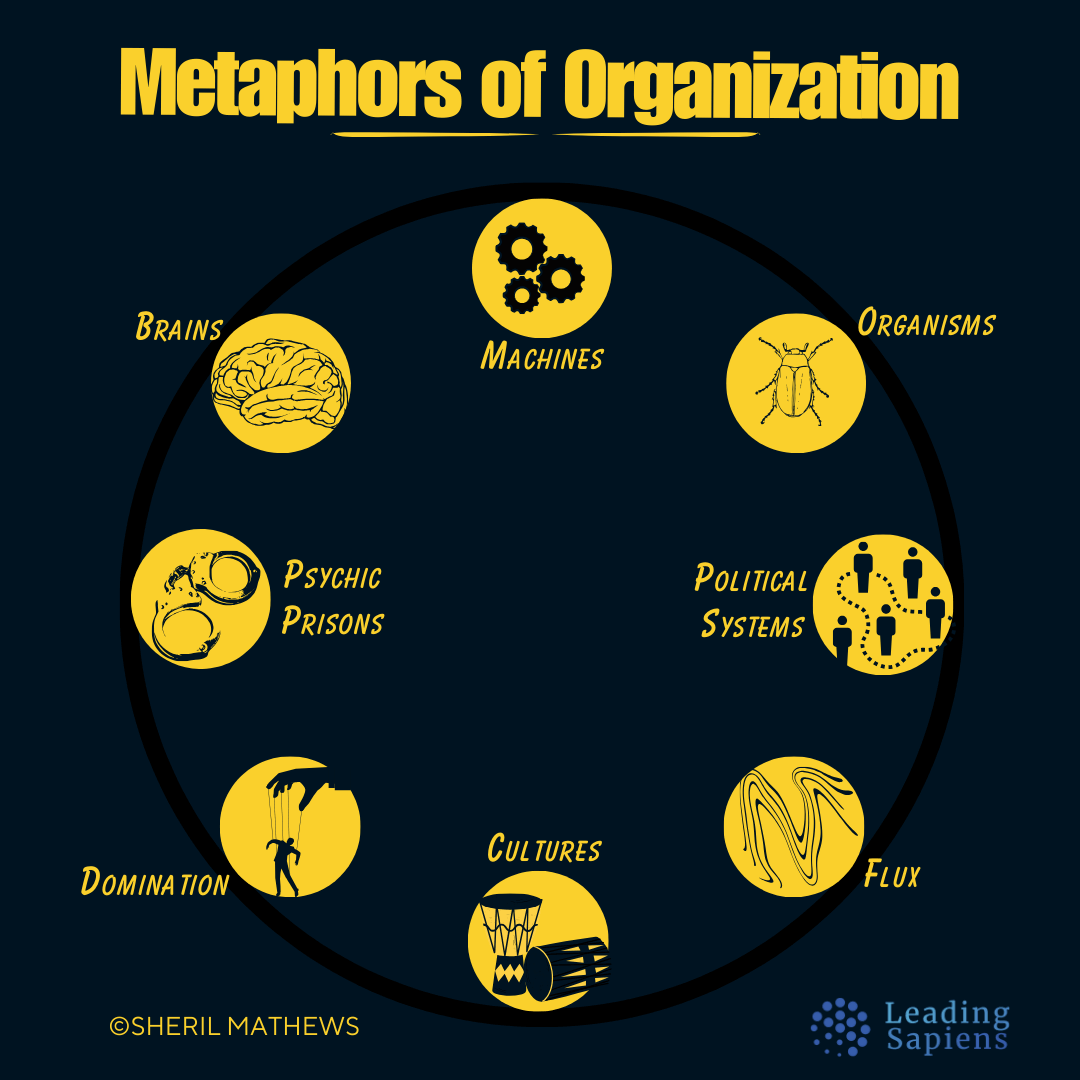

Frames show up in different forms. Sometimes they appear as metaphors: Is this a relay or a chess game? Sometimes they're role-bound: Are we acting as regulators, builders, or mediators? But every frame, as Gareth Morgan reminds us, "reveals something and at the same time conceals other perspectives that might just as readily have been used."

Frames don't just shape interpretation; they generate their own momentum. They filter which details are noticed, which causes are deemed credible, and which responses feel justified. They also influence tone: a problem seen through a learning frame invites curiosity, but through a threat frame, it invites defensiveness.

Once established, frames resist revision. You stop noticing what doesn't fit, or explain it away. The result is tunnel vision dressed as clarity. This creates a frustrating dynamic: teams that keep rehashing the same issue — armed with more data each time — but nothing changes. The problem isn't information. It's the frame.

Behavioral scientists like Kahneman and Tversky have long shown how framing shapes decision quality. The same set of facts, framed in terms of potential loss rather than gain, radically shifts people's preferences. In leadership, this becomes a structural liability; if your frame is off, no amount of analysis will lead to the right decision.

This is why some teams over-index on tools, models, or dashboards. They're solving a technical problem inside a misdiagnosed frame. The result is a sophisticated answer to the wrong question. The real danger isn't just using the wrong frame; it's not realizing you're in one, and that there are alternatives.

Why Multi-Frame Thinking Matters in Leadership

Many leadership misfires stem not from poor execution, but poor framing. This includes misreading situations, misjudging the nature of problems, or mistaking symptoms for causes. Essentially, it's a failure in sensemaking rather than a skill gap.

Fixed frames become invisible blinders

Frames help leaders simplify complexity. But every frame is a reduction. It highlights some dynamics while muting others. A structural frame makes hierarchy visible but downplays power plays. A human resource frame explains motivation but can miss broken systems. A political frame surfaces hidden agendas but can distort into cynicism. And symbolic framing taps into culture and meaning, but can drift into theatrics if ungrounded.

If you’re locked into one, you’re not just limited, you’re blind.

The real danger of a dominant frame is that it feels like reality. Once a frame is in place, it becomes self-sealing. You stop noticing what it leaves out. You interpret disconfirming data as noise or outliers. And you defend the frame rather than update it.

Gary Klein calls this frame-preserving behavior. Instead of questioning the frame, we distort perception of events to keep our mental model intact. It’s not irrational, just protective. But it comes at a cost; you stop seeing what’s actually happening.

In medicine, this shows up as diagnostic closure: the tendency to latch onto an early diagnosis and ignore later signs that contradict it. In leadership, it shows up when a team keeps trying to “execute better” without realizing they’re solving the wrong problem.

Complex problems require multi-frame navigation

Multi-frame thinking helps leaders surface the invisible, revealing the deeper structure behind noise. It helps them hold multiple, conflicting explanations in tension long enough to avoid premature closure.

That matters because most real-world problems are messy. They are:

- Multi-causal: Where structural flaws, misaligned incentives, cognitive biases, and historical baggage create tangled webs of causation.

- Ambiguous: Where success metrics aren’t obvious and every path has trade-offs.

- Dynamic: What worked last quarter destabilizes the system this quarter

- Socially constructed: Meaning depends on who’s looking and from where

These aren’t problems you “solve” so much as problems you “navigate.” And effective navigation demands multi-frame thinking.

Perspective is leverage

In complex systems, perspective is invaluable. Those who can reframe the conversation change the available options. They widen the solution set not by being clever, but by seeing differently.

It's the difference between restructuring reporting lines (structural) and noticing people are competing for the CEO's attention (political). Between calling someone 'resistant to change' (structural) and seeing they're mourning the loss of their expertise (human resource).

Double-loop learning — the ability to question your governing assumptions — relies on this kind of frame-switching. Without it, it’s easy to get trapped in single-loop spirals of tweaking tactics without shifting strategy.

Framing is upstream of action

Decisions are downstream of interpretation. Before choosing a path forward, you’ve already chosen — consciously or not — how to see the situation. A leader’s framing of an issue shapes the questions asked, relevant stakeholders, and viable solutions. As Donald Schön put it,

When we set a problem, we select what we will treat as the ‘things’ of the situation…we frame the context in which we will choose goals and means.

This is how leadership gains upstream leverage. The real differentiator is the ability to notice and shift the operating frame. Action flows from interpretation. Better frames lead to better decisions.

Clarity starts with frame awareness

Misunderstandings in organizations often aren’t due to lack of data, but mismatched frames. One team sees a quality issue, another a branding risk, while a third sees a cost problem. Everyone’s solving for something different because they’re interpreting reality through different lenses.

Effective leaders don’t just push their preferred frame harder. They learn to listen across frames. They recognize when they’re having a disagreement of substance versus a disagreement of perspective. In doing so, they gain interpretive leverage: the power to translate, reframe, and broker shared understanding across silos.

Misalignment often indicates a frame conflict

Intractable conflicts persist not because people refuse to compromise, but because they can't agree on what's at stake. In the Israel–Palestine conflict, both sides have compelling stories about the same piece of land, but they're telling different kinds of stories. One is a tale of ancestral return. The other is a tale of unjust displacement. It's not a debate over facts but a conflict of frames.

The same dynamic plays out in boardrooms and team meetings. When teams disagree, it's tempting to assume one side lacks the facts. But often, the deeper issue is they're not solving for the same thing. A political operator may see a decision as one of coalition-building and influence. A structural thinker may see it as a question of process design. They're not resisting each other's ideas; they're operating in different interpretive universes.

This is why more information doesn't resolve the conflict. It's not a matter of data—it's a matter of perspective. Those who can reframe — offer a new lens that sidesteps the stuck storyline — become unsticking agents. They move people, from entrenched opposition to possibility, by changing the frames of interpretation.

Ambiguity requires agility with frames

The more complex the environment, the more inadequate any single frame becomes. Rigid framing creates brittle leadership. You force-fit every situation into your preferred mental model and miss what doesn’t fit. But fluid framing makes space for discovery. It allows you to ask, “What else could this be?”

In ambiguous, high-stakes settings, the most useful skill isn’t having the right answer. It’s knowing how to toggle between frames to find a more useful question.

Framing is a leadership act

It’s easy to treat framing as an internal mental exercise. But the best leaders do more than that. They frame for others. They shape how their teams, organizations, and stakeholders interpret events.

Leaders help people navigate ambiguity by naming what’s happening in a way that feels coherent, values-aligned, and action-generating. They offer language and logic that transforms disorientation into direction.

That’s how framing becomes a public act of leadership sensemaking.

Multi-Frame Thinking as Sensemaking

Leaders don't just need multiple frames, they also need the judgment to navigate between them. This is where multi-frame thinking becomes sensemaking: the ongoing process of reading situations, choosing interpretive lenses, and adapting as reality unfolds.

But this skill comes with built-in tensions that leaders must learn to manage.

Analysis vs. action

The biggest risk of multi-frame thinking is getting stuck in interpretive loops, endlessly reframing without acting. But expert performers learn to use frame-switching as a rapid diagnostic tool, not an endless search for perfect clarity.

Gary Klein's research showed that expert performers don't always have more information, but better frames. They recognize situation patterns faster and improvise effectively. As Weick described, in moments when normal order collapses, the difference isn't who's smartest, but who can generate enough interpretive coherence to act.

"People discover what they think by looking at what they say, how they act, and what the situation seems to require."

—Karl Weick

"How can I know what I think until I see what I say?"

—E.M. Forster (quoted in Weick)

Action precedes clarity, not the other way around. Leaders don't wait for perfect understanding, they act to gain it. They're constantly rebuilding their mental map as they go, shaping the story in real-time through choices and interpretations.

This is leadership as active sensemaking: learning by doing, adapting on the fly.

Frame quality and the trap of sophistication

Not all frames are created equal. Some illuminate more than they obscure, some lead to action while others create paralysis. The skill isn't in having multiple frames, it's in recognizing which ones generate insight and which ones are mental decoration.

The sophistication trap is real: leaders who use frame-switching to avoid hard choices rather than illuminate them. You'll hear phrases like "Well, it depends on how you frame it" offered as a way to dissolve disagreement without resolution.

This is dangerous when leaders use it to avoid uncomfortable tradeoffs. Reframing isn't a substitute for hard choices; it's meant to illuminate what those choices are.

As Schön suggested, good frames help see more, not less, and lead to richer action, not paralysis. A skilled leader must know how to choose them, not just toggle between them.

The politics of framing

Frame conflicts aren't just intellectual disagreements, they're contests for interpretive authority. The frame that wins shapes budgets, priorities, and careers. This is why reframing can feel threatening even when it's useful. In that sense, it's a form of power.

People don't resist change, they resist having their frame displaced. This is especially true when a new frame threatens status, undermines identity, or exposes hidden tradeoffs. The leader's task is recognizing this political weight and knowing when to introduce a new lens and bring others along.

From Certainty to Frame Consciousness

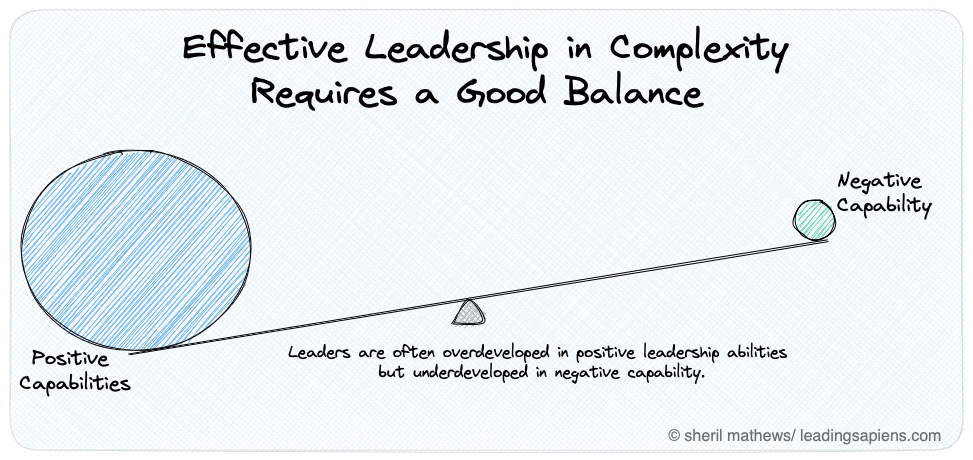

In most organizations, leadership is still seen as a function of decisiveness, clarity, and vision. But there's a paradox: the better you get at something, the narrower your interpretive range becomes. What starts as competence crystallizes into cognitive rigidity. The patterns that once served you begin to constrain you.

Multi-frame thinking is a deliberate countermeasure to maintain cognitive flexibility while deepening domain knowledge.

In Eastern philosophy, the ability to hold complexity without needing to resolve it is associated with wisdom. Keats called it negative capability. Aristotle called it phronesis: practical wisdom that operates in the space between rules and improvisation. In modern organizations, we might call it strategic phronesis: the cultivated capacity to read a situation, frame it with discernment, and act with grounded flexibility. This is how you stretch your interpretive repertoire so you're not trapped in a single reading of reality.

But it requires the willingness to hold your expertise lightly. The best leaders develop what we might call frame consciousness: the ability to notice when they're locked into a particular lens and the discipline to question its usefulness.

The most powerful shift a leader can make isn't always to provide a better answer. Sometimes, it's to ask a better question, from a better frame.

If you aren't changing the frame, are you really leading?

Related Reading

Sources

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2017). Reframing Organizations.

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2014). How Great Leaders Think.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner.

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations.

- Klein, G. (1998). Sources of Power.

- Macdonald, H. (2018). Truth: A User’s Guide.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational Learning.

- Snowden, D., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making. Harvard Business Review.

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline.