Why is it that the most critical information is often the very thing that remains unsaid? Leaders tend to operate under the illusion that communication is a simple, linear process of "telling"—setting direction, articulating values, and dispensing expertise. Or at best an “exchange”.

Yet, the higher they rise in an organization, the more difficult it is to get to the truth. This creates a growing gap between the apparent words they speak and the underlying reality of the human systems they lead.

Bridging this chasm is where the work of Edgar Schein’s foundational work on Process Consultation [1] comes in. In this piece, I first look at Schein’s framework of levels of communication based on the Johari Window and then its implications for effective leadership.

The Four Levels of Communication

Schein’s philosophy of "helping" applies to every human relationship, whether between a manager and subordinate, or a parent and child.

It starts with the counterintuitive premise that the helper—no matter how experienced—is often ignorant of the “client’s” internal reality. We can only truly help others to help themselves. This means shifting our focus from the "content" (the what) to the "process" (the how).

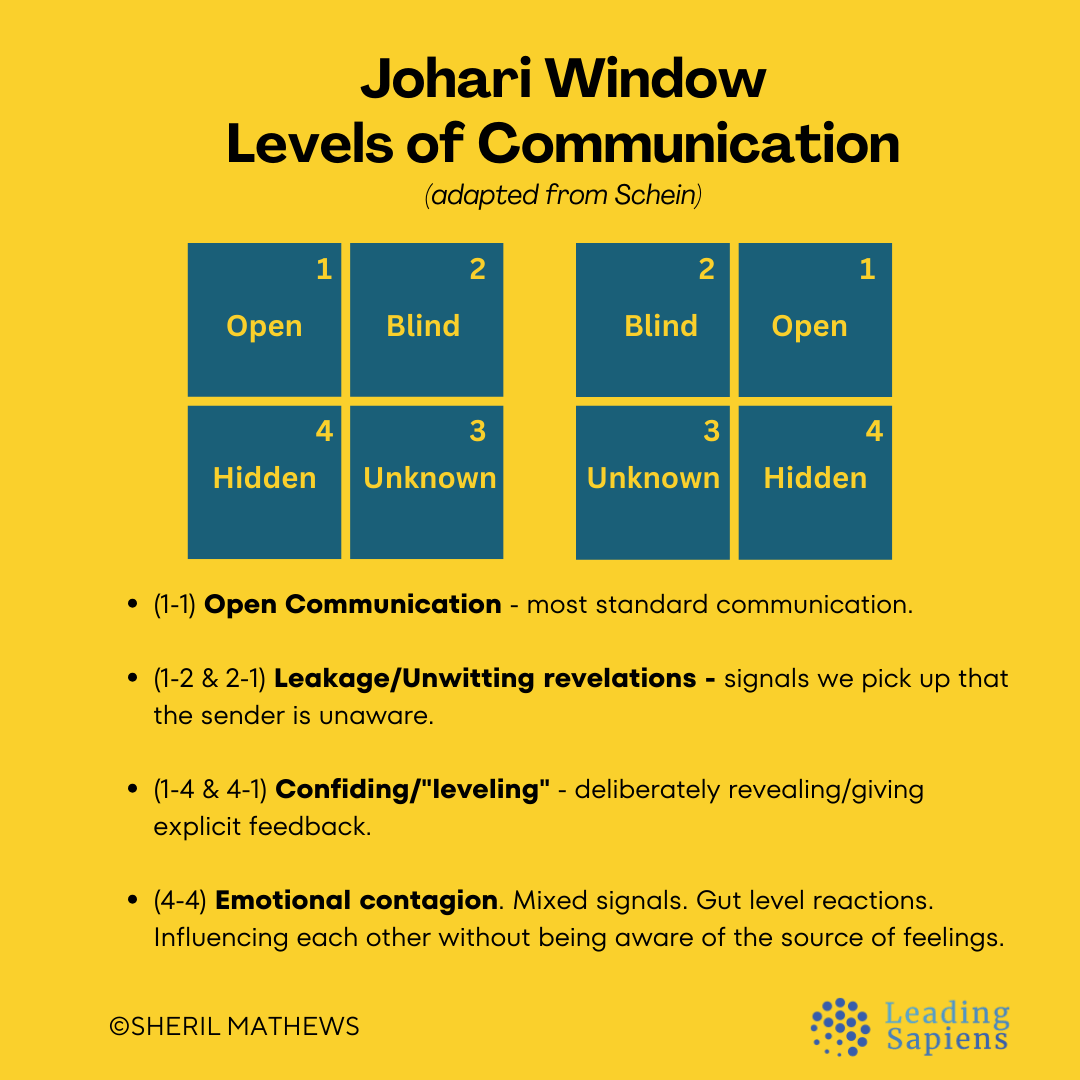

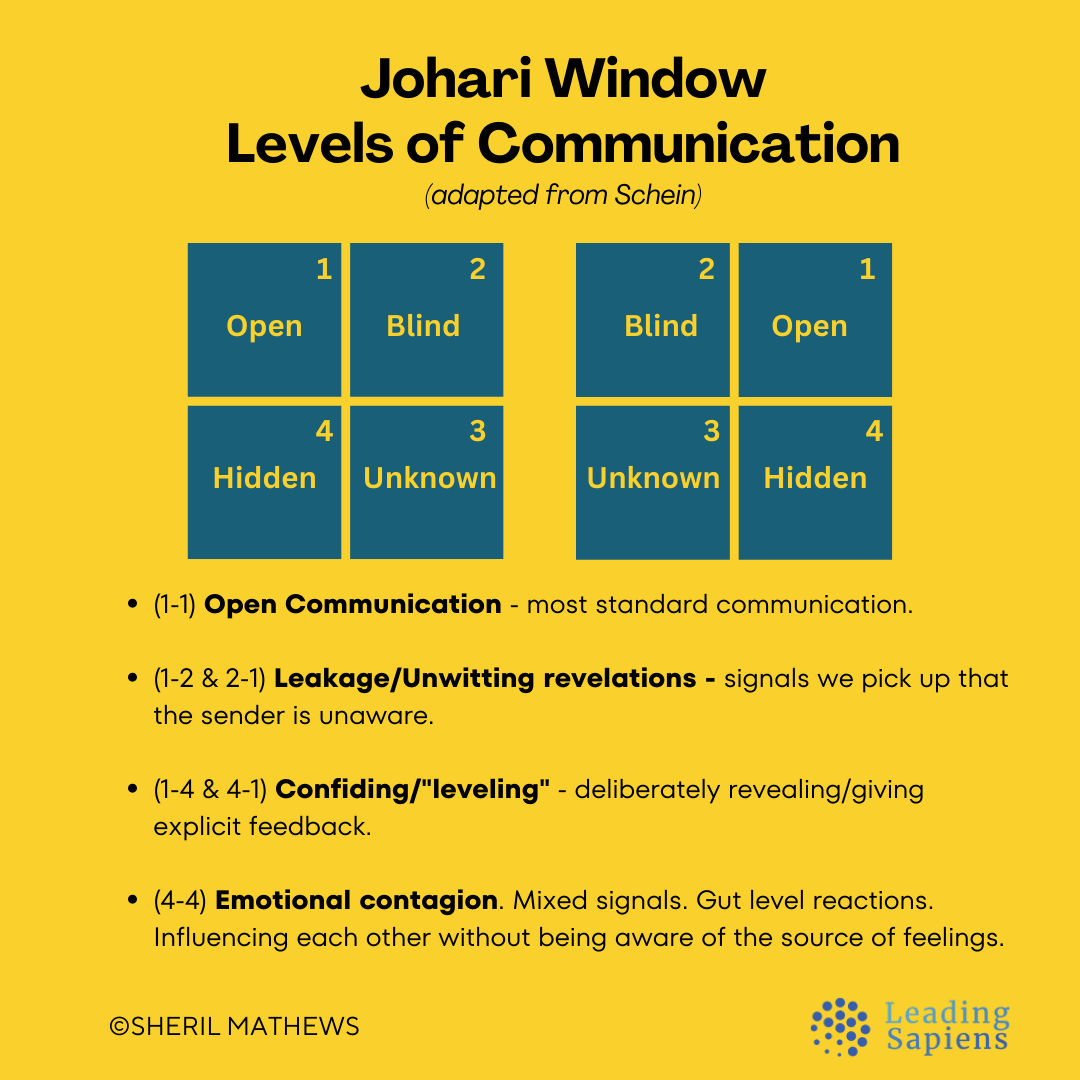

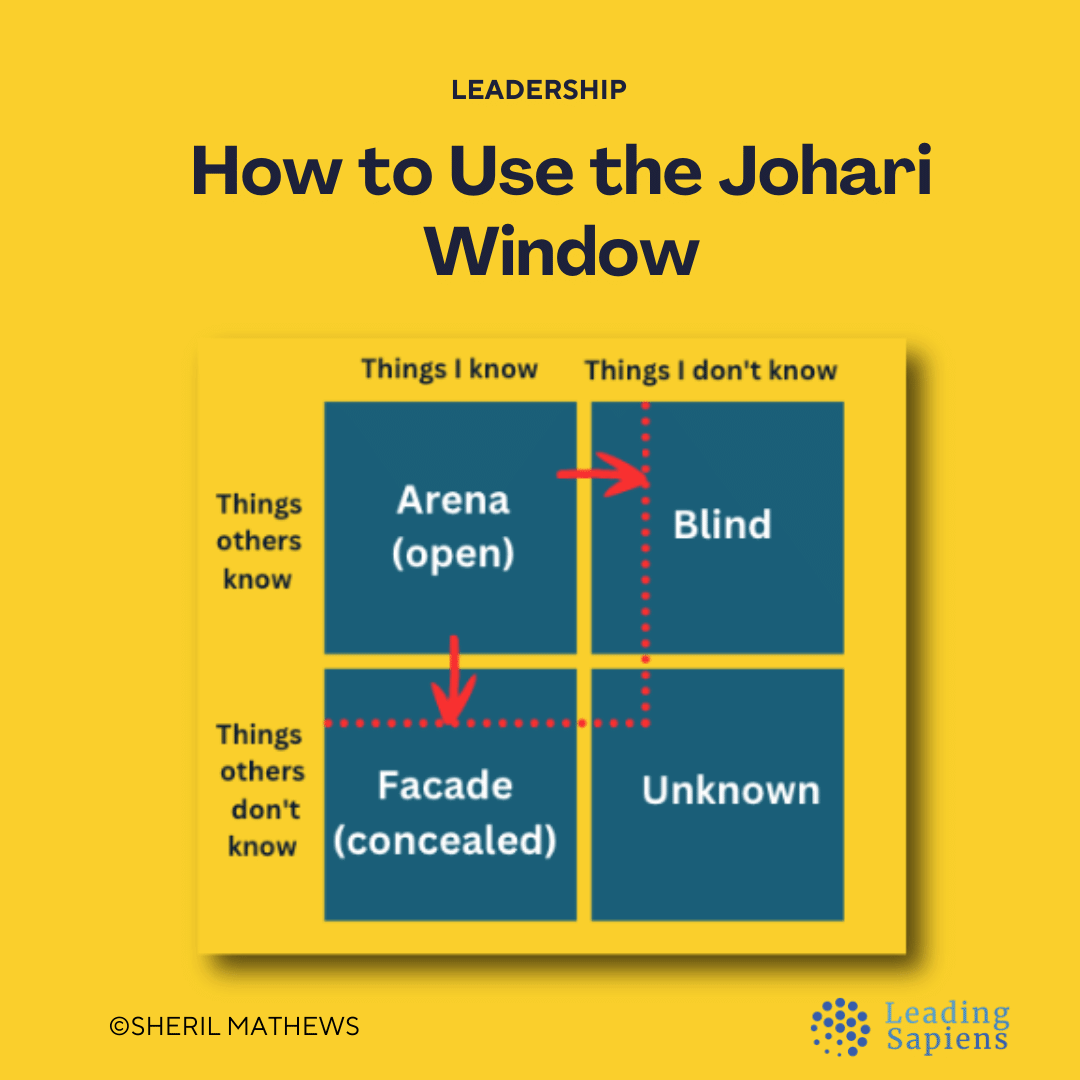

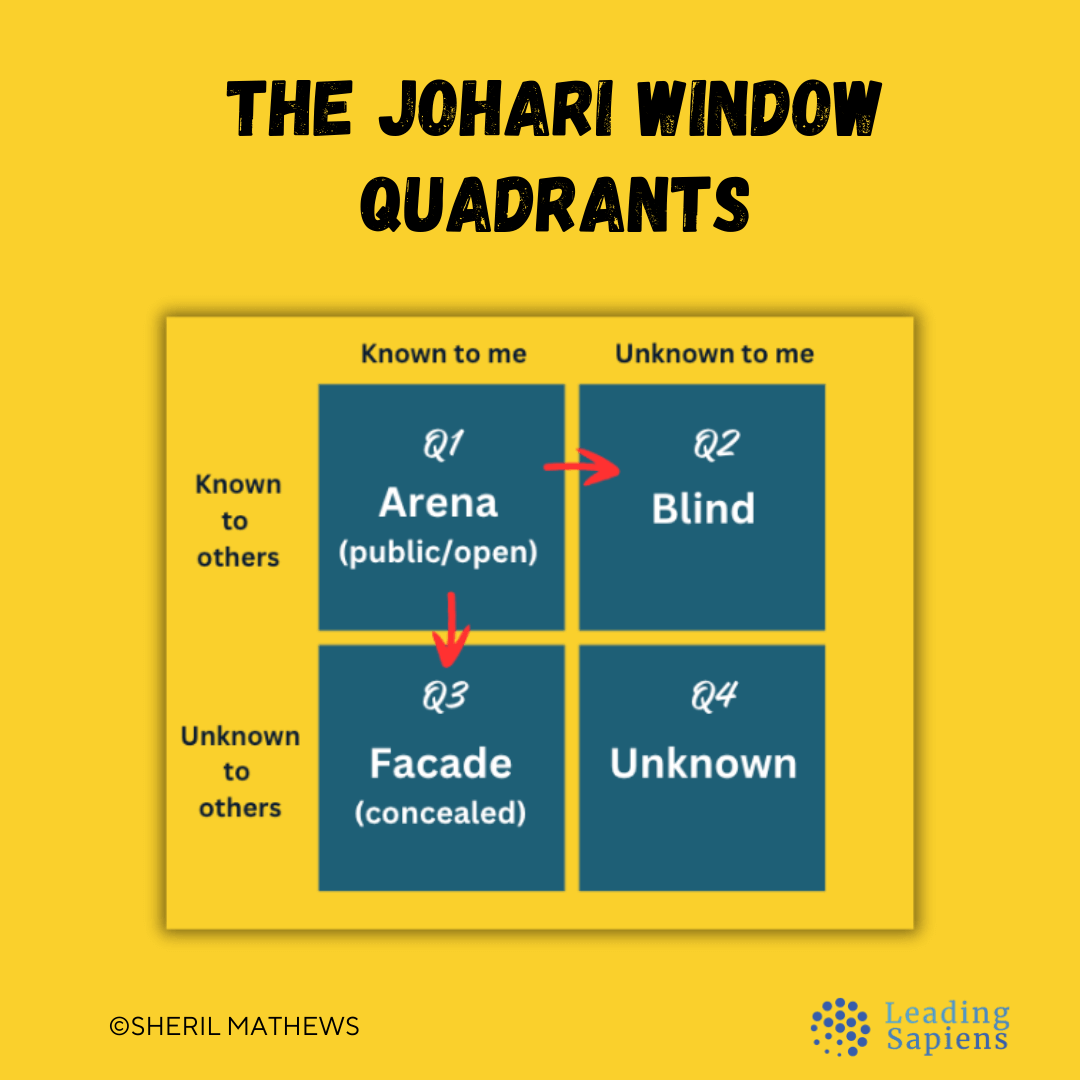

Schein provides a map of this process using the Johari Window— a mental model that divides the "self" into four quadrants: the open, concealed, blind, and unknown selves. This architecture shows how whenever two people interact, they are not simply exchanging data but more like an "interactive dance" where multiple meanings are transmitted across distinct layers of connection.

He identified four specific levels of communication in his framework:

(1) Open Communication (manifest level)

The first level of interaction is between the open selves/quadrants of two individuals. It consists of information, feelings, and data that we are consciously aware of and are willing to share, even with strangers.

In a professional setting, this typically involves information/data, explicit stating of a position, or the exchange of "name, rank, and serial number".

Most popular analyses of communication are confined to this level, focusing on the “content” of the discussion. While this is the most common form of interaction, it is rarely the most revealing.

That’s because cultural rules and social norms of "face work"—the necessity of maintaining our social value—dictate that we generally stay within safe, polite boundaries at this level. Because we’re taught from childhood to be diplomatic and tactful, the manifest level is used to sustain our "claimed selves" rather than reveal our true internal states.

Thus, it acts as a professional and social "uniform"—safe and predictable, but often lacking the congruence needed for high-stakes trust.

(2) Unwitting communication (leakage level)

The second level involves signals picked up from a person's blind self — the parts of our personality, feelings, and impulses that we unconsciously conceal from ourselves, but that remain visible to everyone else.

But we "leak" our true internal states through subtle cues that bypass our conscious control, including:

- Tone of voice and vocal inflection.

- Body language and posture.

- The timing and cadence of our speech.

- Emotional intensity and facial expressions.

These are meanings we as a sender are unaware of transmitting, yet the receiver picks them up clearly. A classic example is the executive who insists “I’m completely open to feedback”, all while their crossed arms and tightened jaw suggest exactly the opposite. This gap between the spoken word and the transmitted signal is the essence of "leakage".

When "leakage" occurs, the receiver gets a double message: a manifest apparent message from the open self and a latent hidden message from the blind self. This creates confusion in professional relationships. The receiver must decide whether to respond to the polite words or the aggressive tone. Often, this leads to a state of conflict or "emotional contagion," where the sender's unacknowledged tension unknowingly affects the receiver, making them feel inexplicably anxious without knowing why.

For high performers and leaders, unwitting communication shows why seeking deliberate feedback is critical. Because we cannot remove our blind spots by ourselves, we require another person to reveal what we’re culturally scripted to conceal.

Moving toward effective leadership requires shifting from “advocacy” to “inquiry”, where curiosity about one's own blind spots and those of others can transform a mere exchange of data into an actual dialogue.

(3) Confiding (leveling)

Why is the phrase “let me level with you” so disarming? That’s because it signals a sudden shift in the architecture of a conversation, moving from the safe, scripted boundaries of polite interaction into a space of high-stakes honesty. This is Confiding, or Leveling—the third level of communication.

It occurs when we deliberately choose to reveal something from our concealed self—the area containing information we ordinarily keep hidden:

- Private reactions or immediate feelings about the other person that we judge as too impolite or hurtful to reveal face-to-face.

- Insecurities or memories of past failures that are inconsistent with our public self-image.

- "Undiscussibles" or the "dead rats" that everyone knows exist but no one is willing to acknowledge.

Leveling is actually a deliberate violation of deeply held cultural rules. Most of our daily interactions are governed by social norms. We routinely conceal our true reactions to avoid humiliating others or appearing tactless ourselves.

When we choose to "level," we are essentially suspending these rules of social economics to share a more private layer of our reality. We make ourselves vulnerable to the other person’s reaction, gambling that the revelation will build a bridge rather than a wall. This is why leveling is a critical to building trust — it provides evidence that we value the relationship more than we value the protection of our own "public face".

(4) Emotional contagion

The final and less common level is what Schein called emotional contagion — a subterranean current where one person influences the other without either party being consciously aware.

It manifests in two distinct patterns:

- Mirroring: This happens when the recipient unconsciously adopts the same emotion as the sender. If a leader denies their internal tension but "leaks" it through their presence, the receiver may begin to feel inexplicably tense or anxious as well.

- Conflict and confusion: This occurs when a sender transmits a "double message". The receiver is presented with a manifest message from the sender's Open Self (such as a polite statement) while simultaneously sensing a latent message from the sender's Blind Self (such as unacknowledged anger). The resulting tension in the receiver stems from a fundamental uncertainty: should they respond to the polite words or the aggressive underlying feeling?

Unlike the first three levels of communication, this exchange bypasses the conscious thought process entirely. It operates as a hidden force that can either build an unspoken bond between people or create an atmosphere of unacknowledged, persistent conflict.

Implications for Leadership

Leadership is not merely a role but a relational engagement that thrives or withers based on how effectively you navigate the four levels of communication. Sensing which level is active in any interaction is a key aspect of leadership sensemaking – a prerequisite for leading effectively.

Let’s look at some implications of Schein’s framework to leadership.

The transactional trap

Most leaders operate almost exclusively at the manifest level (Open Communication), exchanging data and role-based instructions. While efficient for simple tasks, this "professional distance" creates a vacuum of information.

The trap is to assume that clear "telling" is the same as effective leading. Leaders believe they have fulfilled their duties by clearly stating their expectations. But complex, "messy" problems cannot be solved through Level 1 transactional communication alone.

To move toward effective dialogue, leaders must acknowledge their own "blind self" and invite others into a Level 2 relationship—one characterized by "whole-person" interaction that goes beyond mere role-based transactions.

It requires a shift away from a "Culture of Tell" toward a spirit of inquiry, where the goal is not just to exchange manifest data but to build a shared set of meanings.

Silence kills

Because of cultural norms, to point out a leader’s error or a team's systemic failure is to risk social murder—humiliating another and, in the process, appearing tactless or unreliable oneself.

In high-hazard industries—such as nuclear power, aviation, or surgery—the failure to identify these “undiscussibles” can be fatal.

Research into disasters like the NASA Challenger or the BP Gulf oil spill often reveals that lower-ranking employees possessed the information needed to prevent the accident but did not feel safe bringing "bad news" to their superiors.

Leaders operate under the illusion that their teams are being frank because of "professional responsibility". However, subordinates are naturally sensitive to status cues and will withhold critical data if they perceive that "speaking truth to power" results in indifference, impatience, or retaliation.

When subordinates feel it is unsafe to correct a superior, they may withhold critical safety information to avoid causing the leader to lose face. Therefore, a core leadership task is to create psychological safety—a climate where it is safe to reveal what’s ordinarily concealed.

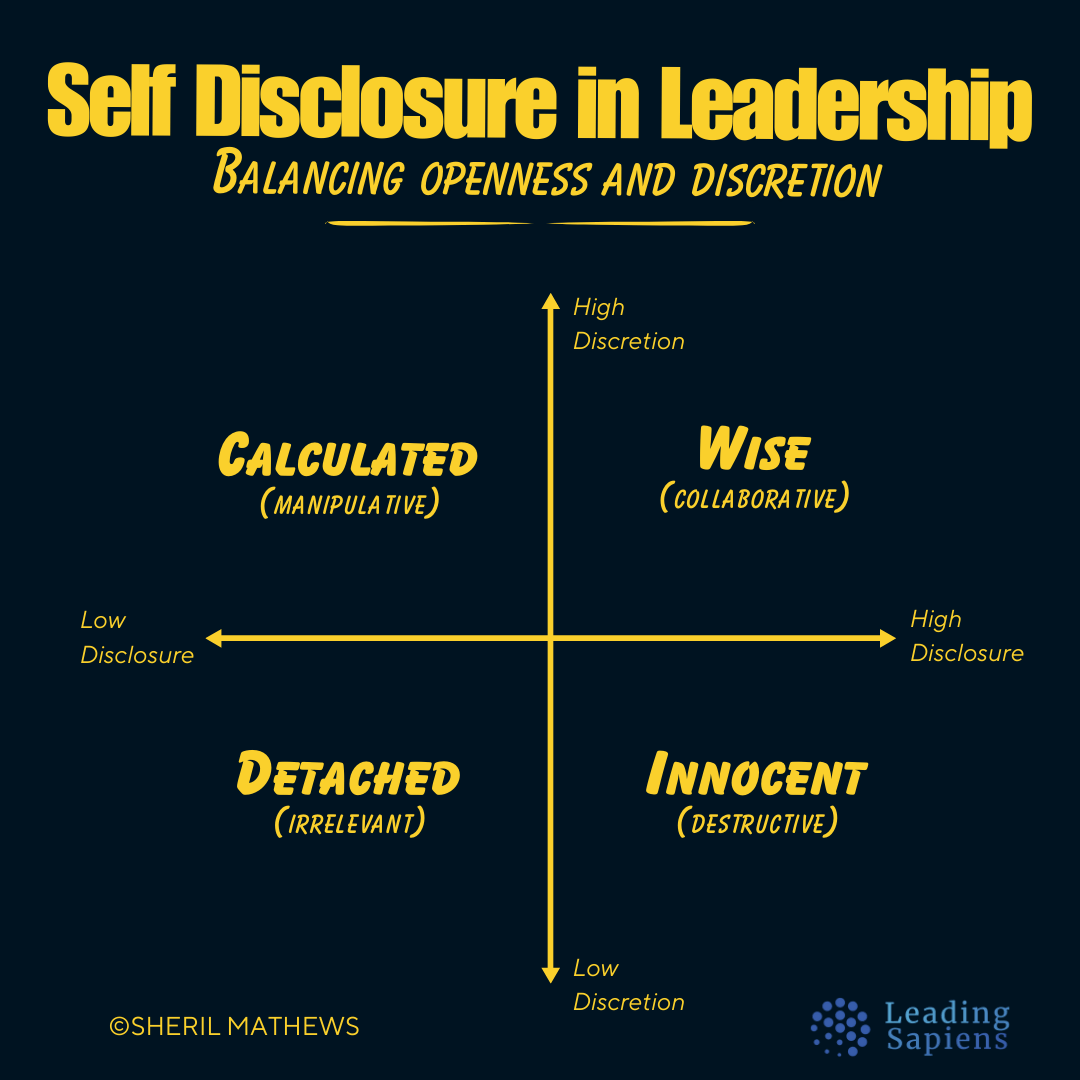

The art of leveling up

For leaders, the ability to initiate leveling is a prerequisite for moving beyond "Level 1" transactional relationships.

Open manifest communication often fails because subordinates, trapped by cultural norms, withhold the "real problems” to avoid looking incompetent. True exchange only becomes possible when the communication channel is "equilibrated," allowing for honest disclosure. A person cannot remove their own blind spots unless the other party is willing to reveal—through leveling—what they would ordinarily conceal.

Since leveling is a "violation" of social norms, how can a leader make it safe?

Schein suggests creating a "container" or a "cultural island"—a temporary setting like an after-action review where the usual rules of deference and demeanor, rank and status are minimized or even suspended. This includes:

(1) Modeling vulnerability. The higher-status person must typically go first, revealing a personal goal or a doubt to give others "permission" to do the same. This shift from debate to dialogue ensures everyone is finally talking the same language which is the bedrock of true organizational learning.

(2) Humble Inquiry. Instead of telling, the leader asks open-ended questions that minimize the "one-down" feeling of the subordinate.

(3) Specific feedback. Leveling works best when it is descriptive and behavioral rather than judgmental. Saying "I felt ignored when you interrupted me" is a productive form of leveling. In contrast, saying "You are rude" is a threat that triggers defensiveness.

(4) The process review. This is a dedicated period at the end of a meeting to ask: "How did we do? Did we leave anything unsaid?". This forces the group to look at the "how" of their interaction rather than just the "what," making the invisible forces of communication visible.

(5) Status equilibration. In any hierarchy, the leader is "one-up" and the subordinate "one-down". By asking for a subordinate’s preference—such as a surgeon asking a nurse for their input on a tool—the leader acknowledges their own "here-and-now humility". This empowers the lower-status person to speak up across hierarchical boundaries, turning a "telling" relationship into a collaborative one.

Managing "Leakage"

Leaders are often unaware that they are perpetually sending messages from their "blind self" (Unwitting Communication). You might proclaim an "open door policy" but your body language leaks impatience or defensiveness. Subordinates, being highly sensitive to status cues, will always prioritize these latent signals over the manifest words. Effective leadership requires congruence—aligning one’s unwitting signals with one's spoken intentions to build trust.

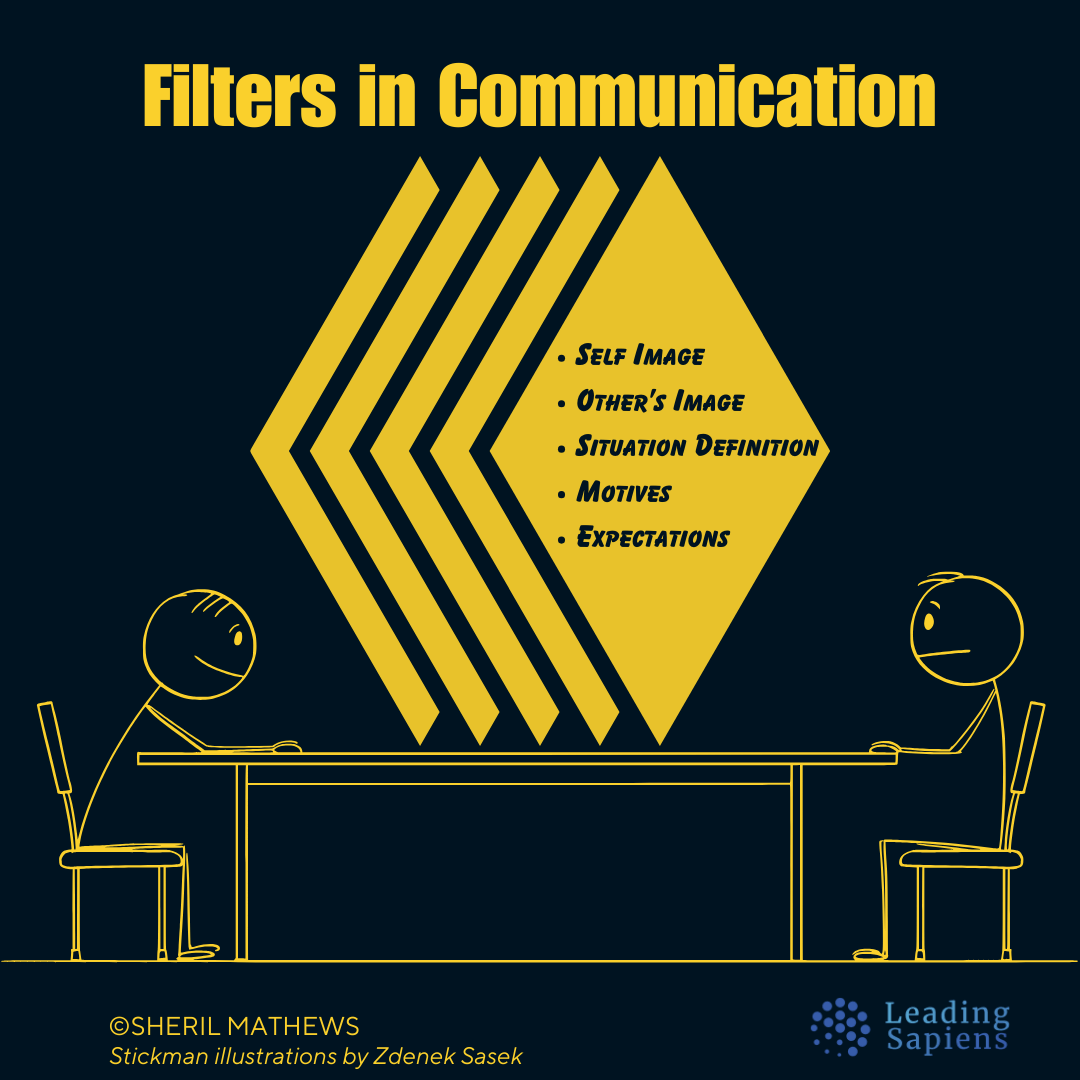

Accessing ignorance

To get better at sensing relevant levels, leaders must master the discipline of what Schein calls “accessing Your Ignorance". This requires an ongoing awareness to distinguish between what's actually known and what is merely assumed based on prior stereotypes or expectations.

By adopting a stance of "Here-and-now Humility," a leader acknowledges their dependency on others for information they do not possess. This shift allows the leader to use Humble Inquiry—asking questions to which they truly do not know the answer—to draw out the "concealed" or "blind" insights of their team.

Sensing becomes more accurate when a leader stops trying to be the "expert" who knows all the answers and instead becomes a "process consultant" to their own team, focusing on how the interaction is occurring rather than just the content of the words.

Transitioning to level 2 relationships

At Level 1, parties maintain distance and apathy toward the other's well-being, which prevents the sharing of "latent" meanings.

A leader senses the need for a Level 2 relationship when the task at hand requires high levels of interdependence, trust, and open communication.

Building this level of connection requires "adaptive moves"—small, intentional acts of personalization, such as sharing a personal doubt or asking about a team member's unique experience. As the relationship moves to Level 2, the "blind spots" that hinder organizational performance begin to disappear because "it takes two to see one": we require others to help us see the signals we are sending unwittingly.

Related Reading

Sources

- Schein, E. H. (1988). Process consultation: Its role in organization development.

- Schein, E. H. (2011). Helping: How to Offer, Give, and Receive Help.

- Schein, E. H. (2025). Humble inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling

- Schein, E. H. (2023). Humble leadership: The power of relationships, openness, and trust.