Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

In the movie A House of Dynamite, an unidentified nuclear missile is inbound towards a major city in the United States. The defense systems designed to stop it have already failed once. Whatever happens next to millions of people hangs on whether the last remaining systems work. There are seconds left.

Needless to say it’s a crisis everyone involved is trained for in theory but not really prepared to respond.

As it unfolds, Captain Olivia Walker (played by Rebecca Ferguson) turns to a junior officer who’s visibly unraveling and reassures him:

This is gonna be over in a minute, right?

End of our shift, we’re gonna be on our way home….

When you look back at this drama, this is gonna be the second most exciting thing that happened to you today. Right?

He answers half-convinced, “Right."

Was the captain’s response the right call? What might you have done in that situation?

The broken heart phenomenon

On September 9, 1965, James B. Stockdale was flying his A-4 Skyhawk low over North Vietnam when antiaircraft fire tore through his jet. Flames engulfed the cockpit. He ejected into hostile territory, knowing in those seconds of free fall that his life had changed.

What followed was seven and a half years in the Hỏa Lò prison, the notorious “Hanoi Hilton.” Stockdale arrived badly injured — his leg shattered in the landing — and faced relentless beatings, rope torture, and years of solitary confinement in a windowless cell. As the highest-ranking U.S. naval officer captured, he became the de facto senior leader of more than four hundred American prisoners.

Several decades later, and now Vice Admiral, when asked in an interview by Jim Collins which POWs didn’t make it out of the harrowing ordeal, Stockdale said:

Oh, that’s easy, the optimists.

Oh, they were the ones who said, “We’re going to be out by Christmas.” And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, “We’re going to be out by Easter.” And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again.

And they died of a broken heart.…

This is eerily similar to what Viktor Frankl observed in equally horrible conditions.

Writing about his experiences at the Auschwitz concentration camp in Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl highlighted the problem of putting hope on a schedule:

The death rate in the week between Christmas, 1944, and New Year’s, 1945, increased in camp beyond all previous experience.

In the chief doctor of the concentration camp’s opinion, the explanation for this increase did not lie in the harder working conditions or the deterioration of our food supplies or a change of wealth or new epidemics. It was simply that the majority of the prisoners had lived in the naive hope that they would be home again by Christmas.

As the time drew near and there was no encouraging news, the prisoners lost courage and disappointment overcame them. This had a dangerous influence on their powers of resistance and a great number of them died.

The duality of faith vs. realism

Both Stockdale and Frankl concluded that survival required a sophisticated psychological duality—what Frankl termed "tragic optimism".

Frankl defined it as "optimism in the face of tragedy". It’s the ability to remain optimistic about the value of life while simultaneously acknowledging and remaining present in the tragedy of one’s circumstances.

Stockdale put it this way:

This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.

Collins later codified this lesson into what he called the Stockdale Paradox [3]:

Retain faith that you will prevail in the end, regardless of the difficulties. AND at the same time, confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.

The seductive lie of either/or and why naive optimism fails

Long, uncertain challenges tempt us toward simplicity. One extreme says: stay hopeful, picture the win, and keep spirits high. The other says: strip away illusion, face the facts, and brace for pain.

Both extremes — blind optimism and bare-knuckled realism — although they feel like strength, leave us brittle.

Modern psychological research shows why Stockdale and Frankl saw the optimists fail. NYU Prof. Gabriele Oettingen’s research into "positive fantasies" shows that merely dreaming about a desired future can actually impede its achievement. Starry-eyed dreaming saps the "initial oomph" and energy required to perform the hard work of meeting real-life challenges.

Stockdale and Frankl’s findings mirror what Oettingen calls "mental contrasting". By juxtaposing a dream with the "pesky reality of day-to-day life," we gain the energy to take constructive action. Conversely, the "ostrich approach" of sticking one’s head in the sand and hoping for difficulties to go away often precludes taking the necessary steps to handle a predicament effectively.

The Stockdale Paradox shows a third way beyond the simplistic binary notions of optimism and pessimism. It's mental jujitsu that sounds contradictory but works as an armor against both despair and delusion — difficult to do but far more resilient.

Two commitments in tension

You can only be an optimist in the long run if you’re pessimistic enough to survive the short run.

— Morgan Housel [6]

Stockdale’s mental discipline built in the horrors of prison and solitary confinement required two seemingly incompatible commitments.

The first: unwavering faith. This wasn’t hope tied to a deadline or a wish that things might get better soon, but a deep, defiant conviction. That long-range faith gave meaning to suffering and kept despair from swallowing the men. It offered a reason to keep moving when no external evidence suggested rescue or victory.

The second: confronting the brutal facts. Stockdale refused to look away from pain, uncertainty, and loss of control. He acknowledged the reality of torture and indefinite captivity, accepted that there was no predictable timeline, and adjusted tactics accordingly. This realism protected prisoners from the psychological whiplash that destroyed the “just-hold-on-until-Christmas” crowd. It also forced practical ingenuity — the small, daily acts of resistance and survival that eventually brought the men home with dignity intact.

Hope by itself is brittle; each disappointment becomes a small crack until it eventually shatters. Meanwhile, realism alone easily turns into cynicism and helplessness. Done together, however, they create a more durable stance that can endure uncertainty without losing either clarity or purpose. It asks you to see clearly without giving up, and to believe fiercely without lying to yourself.

Holding both at once is what makes it a paradox and why it’s hard.

For leaders, this is tricky. Organizations reward clarity and optimism even while bad news threatens morale and careers. Cultures punish those who bring up harsh truths. But teams lose trust when leaders peddle false cheer and fixed timetables.

Navigating that tension — belief without illusion, realism without defeat — is the essence of the Stockdale Paradox.

Leading when you can’t promise rescue

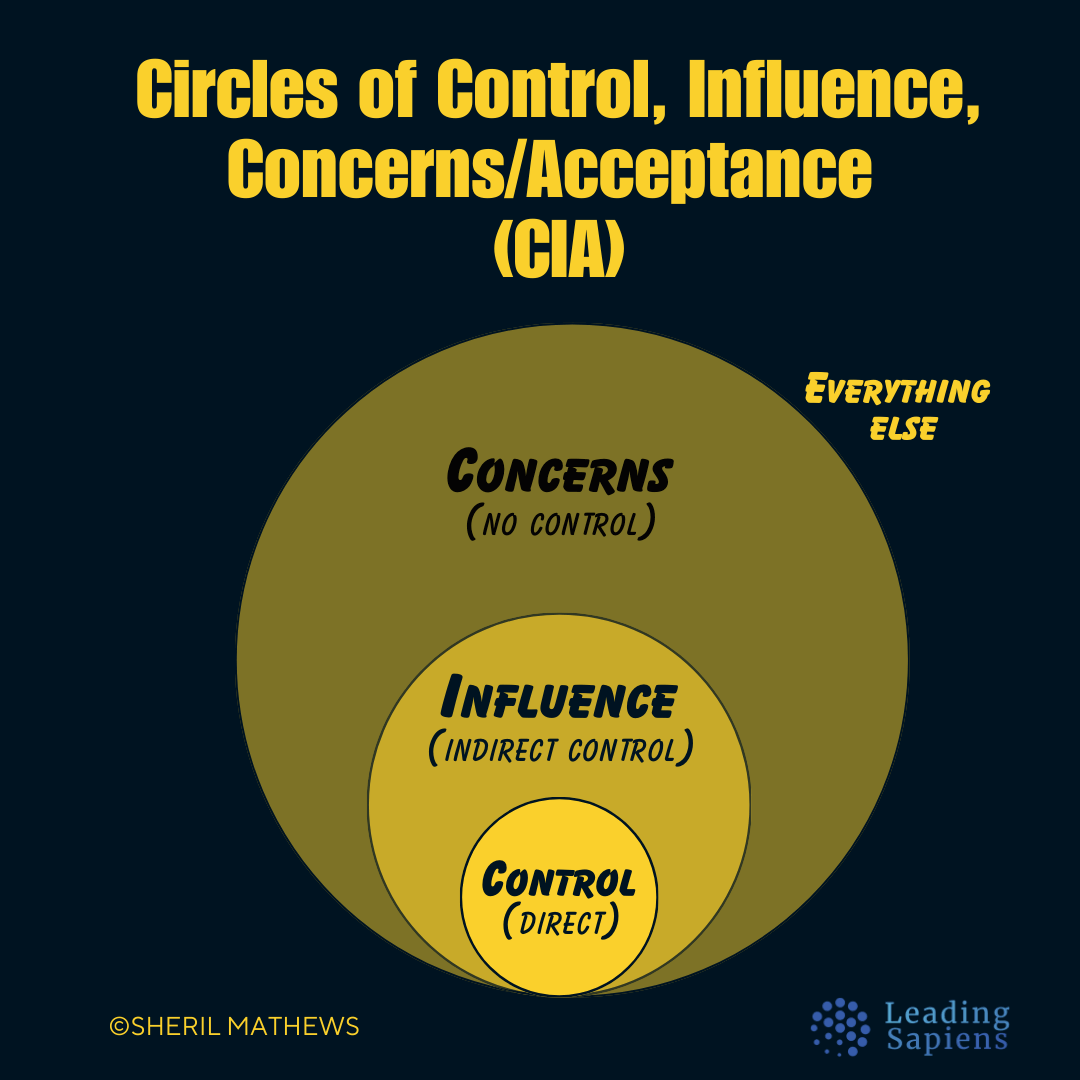

The Stockdale Paradox is an internal stance when the future cannot be controlled or guaranteed. It’s uncomfortable because it denies leaders two easy moves under pressure:

- The first is false rescue. It’s the comforting promise that “everything will be fine soon” to keep people engaged.

- The second is hard fatalism: the stoic-sounding but corrosive message that “this is just how it is, brace yourself.”

Both feel protective — one shields morale, the other shields credibility — but neither are durable. The first disintegrates when promised relief doesn’t come on schedule, while the second drains initiative and trust.

Holding the paradox means leading without certainty. It asks you to articulate a future worth working toward, while simultaneously admitting that the road is unclear and the present is worse than people wish to believe. It means allowing frustration with reality to coexist with belief in eventual success. It’s a form of moral courage: to stay honest without abandoning hope, and to keep hope alive without lying.

Doing that requires self-control, clarity about what you can and cannot promise, and the capacity to keep moving without the psychological crutch of certainty.

If no one is unsettled by your realism, you may be sugarcoating. If no one is stretched by your belief, you may be leading from resignation.

Living the Stockdale Paradox is to operate in that tension.

What would Stockdale do

So in our opening example, how might Stockdale have responded?

The captain didn’t need to invent a future where everyone was safely home by the end of the shift. That kind of reassurance only works if reality cooperates—and on that day, it already wasn’t.

Stockdale probably would have grounded the team somewhere else entirely: instead of an outcome or timelines, he might have focused on what the Buddha called “right effort” and “right action”. Something like:

I don’t know how this ends. But I know this: we stay here, we do our jobs cleanly, and we don’t look away. That’s what’s in our control.

That’s a much harder message to deliver because it offers no relief. But it doesn’t borrow hope from the future, either. Instead, it locates stability in identity and action, instead of rescue.

The Stockdale Paradox is an endurance practice that asks you to hold two forces seemingly allergic to each other. Most of us — and organizations — struggle to stay there. We lurch toward comfort.

Effective leadership lives in that in-between where hope becomes a discipline and realism a responsibility.

Bruce Springsteen [7] said it best:

…to accept the world on its terms without giving up the belief that you can change the world. That’s a successful adulthood—the maturation of your thought process and very soul to the point where you understand the limits of life, without giving up on its possibilities.

How will you respond?

Related Reading

Sources

- Stockdale, J. (1993). Courage Under Fire: Testing Epictetus's Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human Behavior.

- Stockdale, J. (1995). Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot.

- Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don't.

- Oettingen, G. (2014). Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the New Science of Motivation.

- Housel, M. (2023). Same as Ever.

- Stulberg, B. (2023). Master of change.

- Frankl, V. E. (1946). Man’s search for meaning.