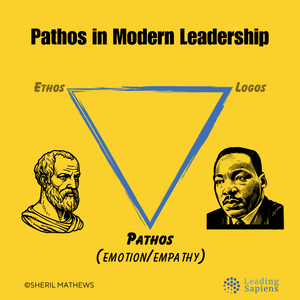

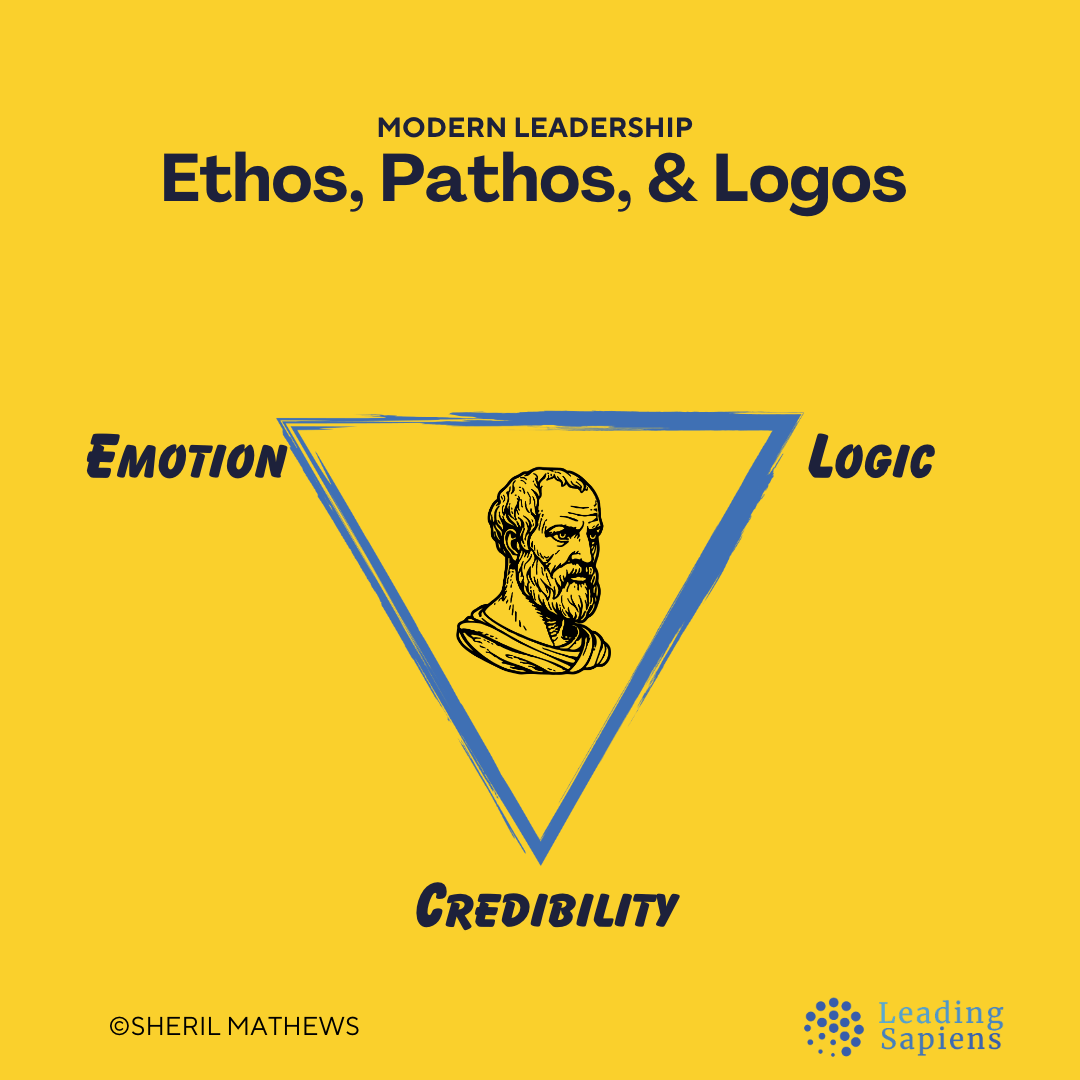

It’s common to associate effective leadership with a cool, detached rationality. We assume that if the facts are right and the plan sound, people naturally follow. Yet, how often have we presented a perfectly reasoned plan only to see it met with indifference? Why is it that logic so often fails to move the needle of human behavior? The answer lies in a 2,300-year-old distinction that modern managers forget: Pathos.

We’re not thinking machines that feel; we are feeling machines that think. Aristotle recognized that while logic (logos) is the "body” of persuasion, it is emotion (pathos) that triggers action.

At the end of reasons comes persuasion.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

The trap of logic

In our modern, data-driven culture, we’ve been conditioned to believe that professionalism means the suppression of emotion. We are taught to be suspicious of emotion, viewing it as a form of manipulation or a waste of time. And that facts are the only legitimate currency of persuasion.

But according to Aristotle, the father of systematic persuasion, this is a fundamental misunderstanding of how humans actually make decisions.

The problem is that people don’t act based on reason alone. When we over-index on logic, we make the audience work too hard to find a reason to care. Reason goes out the window when feelings are not addressed.

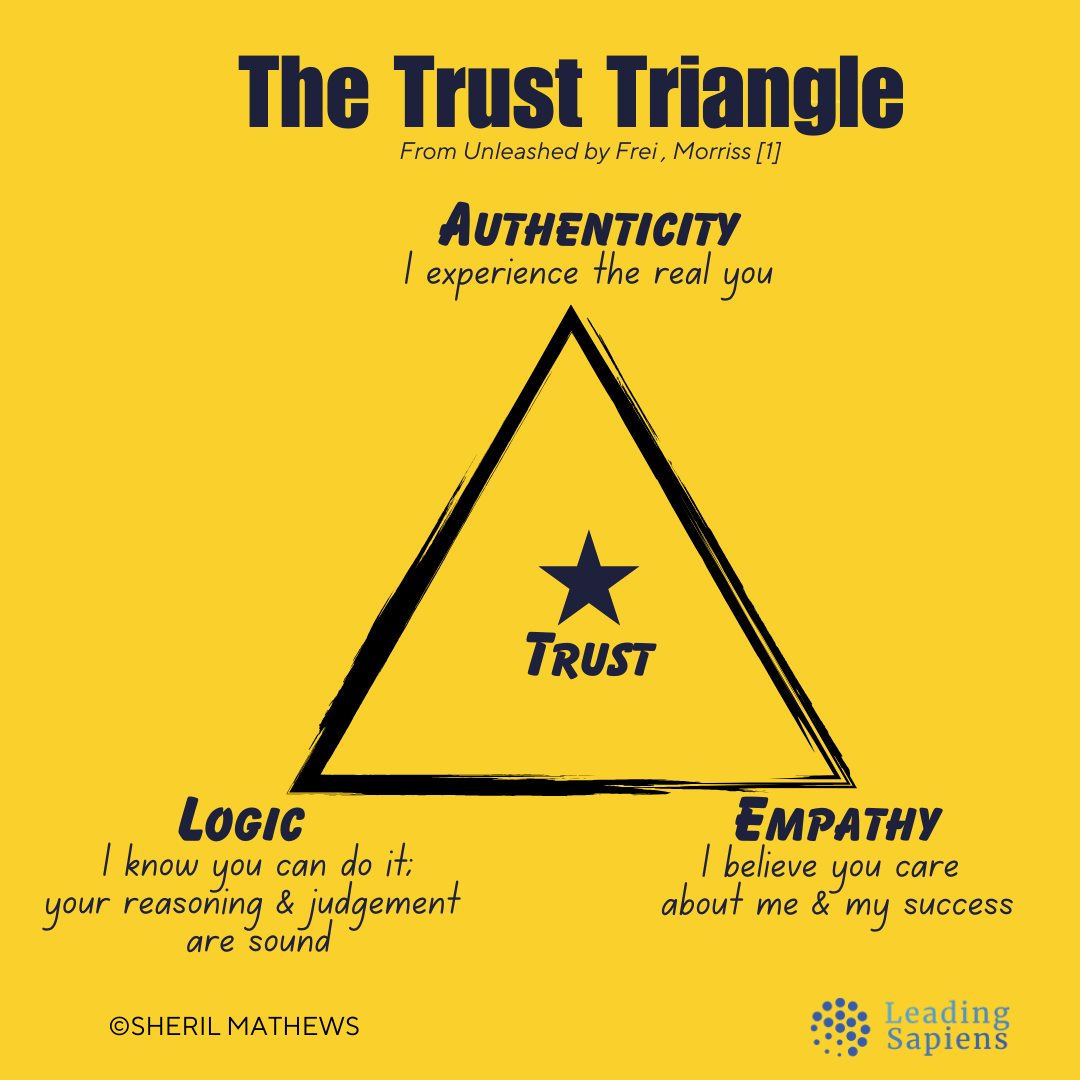

Harvard’s Frances Frei and Anne Morris call this the “empathy wobble”.

In their Trust Triangle framework, trust is built on the three pillars of Authenticity, Logic, and Empathy that mirror Aristotle’s ethos, logos, and pathos. Logos (logic) might convince someone that a plan is sound, but it is notoriously ineffective in moving the human will.

When trust breaks down, it’s usually because one of these pillars has “wobbled”.

An "empathy wobble" is when your team begins to suspect that you care more about yourself, your goals, or your own brilliance than you do about them. This is particularly common among high performers who are analytical and driven to learn. They get so focused on the logic of the problem that they forget the people experiencing it.

This wobble is often the invisible barrier to what Frei and Morris call "empowerment leadership". To fix it, leaders have to develop Pathos — a deep understanding of others’ emotions.

👋 Get my new articles in your inbox 👇

What Pathos Is (and What It Isn't)

In modern parlance, "pathetic" is a term of derision, implying weakness and inadequacy. To the Greeks, however, pathos carried a lot of weight because it meant suffering and experience.

Aristotle did not view emotion as a distraction, but a sophisticated mechanism that directly shapes how we perceive truth. He defined pathos as "putting the audience into a certain frame of mind”.

For leaders, this means recognizing that your team’s emotional state is not a distraction from work but a lens through which the work is evaluated. From this perspective, Pathos is the bridge between understanding choices and taking action.

More than just a feeling, pathos induces a specific state of mind intended to influence judgment.

Our judgments when we are pleased and friendly are not the same as when we are pained and hostile.

When leading others, you are, by definition, asking people to judge a future direction as beneficial or a past failure as a learning opportunity.

Emotions as rational

A common mistake is to view emotions as irrational baggage that interferes with clear thinking. Aristotle gives a different take: emotions are judgment-based. We don’t just feel angry or fearful in a vacuum; we feel that way because of what we believe to be true about a situation.

For leaders, this means that to change a team’s emotional state—from, say, fear of a merger to confidence in a new direction—you don’t need motivational speeches. You need to address the underlying beliefs that are generating the fear.

When teams are resistant to change, they aren't being "difficult." In their current state of mind, the pain of the proposed change outweighs the perceived benefit.

Your task is to investigate the "intentional objects" of their emotion. By treating emotions as data points of underlying beliefs, you can lead with much higher precision.

The three factors of Pathos

Aristotle proposed that to produce a specific emotion in an audience, you must understand three distinct factors:

- The state of mind of the subject: What is the internal condition of the audience?

- The circumstances or stimulus: What specific events or words provoke the emotion?

- The object of the emotion: Toward whom or what is the emotion directed?

If you are wobbling on empathy, it's likely because you have ignored one of these pillars. You are presenting a solution (logos) without first understanding the underlying psychology of your team.

As an example, consider Aristotle’s analysis of anger. He defines it as a "desire, accompanied by pain, for revenge for an obvious belittlement".

One must in each case divide the discussion into three parts. Take the case of anger. We must say what state men are in when they are angry, with what people they are accustomed to be angry and in what circumstances.

Pathos is not about you

Given the importance of Pathos many leaders mistakenly think they must perform with dramatic, high-octane passion. This is a fundamental misunderstanding.

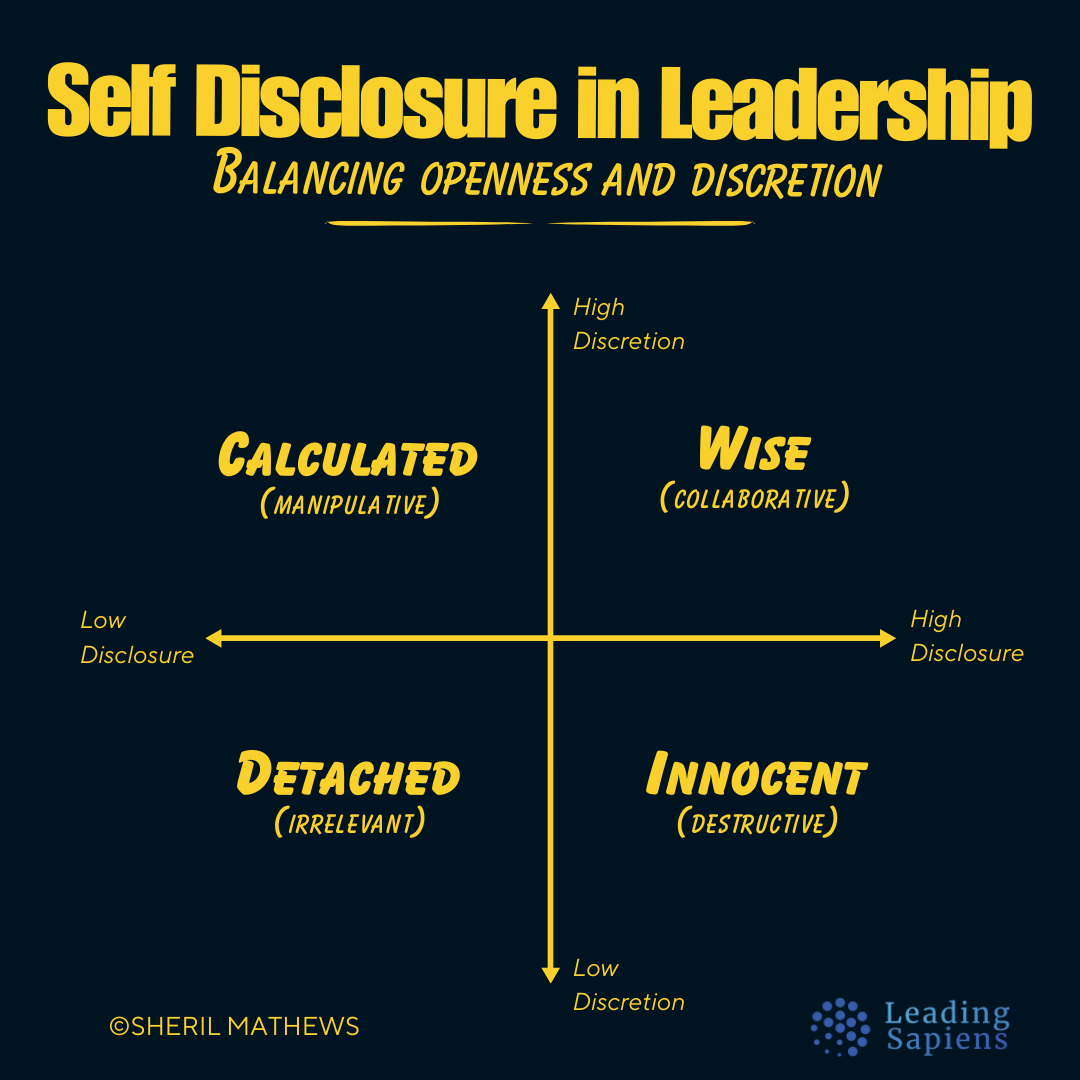

Pathos is not about your emotional state but understanding and modulating the emotional state of those you lead.

Although genuine conviction can certainly be a starting point, it’s not about your passion per se. Failure to persuade often stems from a gap: a strong emotional connection to a decision yourself, but ignoring the distinct emotional state of those you lead.

This is why often leaders who are deeply passionate about a project somehow can’t get their team behind it. They mistakenly believe that their personal passion for the work will automatically inspire and motivate their team. However, they fail to recognize their team's mental state. Without addressing the team’s fatigue or frustration, your passion comes across as a relentless and oppressive pressure instead of an inspiring force.

True pathos begins with sympathy: aligning yourself with the listener's current mood before attempting to change it.

For leaders, this means you are not the protagonist of the emotional drama but the director. Your goal is to move the audience from a state of indifference or hostility to a state of receptiveness. To do this, you must stop asking "How do I feel?" and instead ask "What is the current emotional baseline of my team, and where do I need it to be for this decision to make sense?"

Emulation is powerful

Pathos also includes emulation: our emotional response to role models we admire. Aristotle noted that we are more likely to be persuaded by those we perceive as having a cause larger than themselves.

This is why leaders who walk the talk—like Yvon Chouinard of Patagonia—are so influential. Their authenticity creates a "flywheel of trust" that allows them to lead at scale, even in their absence.

By revealing your own "high standards and deep devotion," you invite others to reach for a better version of themselves. You are using pathos to create a community of people who want to do the right thing, instead of a workforce of automatons who merely follow orders.

Sincerity vs. manipulation

Is pathos manipulation? The ancient Greeks wrestled with this. Plato viewed rhetoric as a form of flattery, a knack for producing gratification rather than truth. Aristotle, more pragmatically, believed that while logic should be enough, the "baseness of the audience" made the study of pathos necessary.

For the modern leader, this line between persuasion and manipulation is indeed thin.

The balance is achieved through intent and connection. Using emotional triggers to distract from a flawed plan is manipulation. In contrast, using them to help a distracted team grasp the importance of a sound plan is leadership.

The most effective pathos is based on a genuine respect for the other’s worldview.

Ways to practice Pathos

Following are some ideas to move your audience based on Pathos.

1. Bending reality using storytelling

Logic comes across as cold and calculated, whereas stories are like a shared experience. Stories convince where logic only informs because they humanize and transform impersonal fragments of data into a pattern with a purpose. While a list of facts might trigger the skeptical System 2 brain, a story engages the instinctive System 1 brain, which is far more amenable to persuasion.

Aristotle emphasized “enargeia”— painting a mental picture so vivid that the audience feels they are experiencing the events themselves. A detailed story — a "perfectly pathetic tale”— creates a vicarious experience and makes the audience feel that this could happen to them.

In his "I Have a Dream" speech, Martin Luther King Jr. did not merely lecture on civil rights. Instead, he used the metaphors of “promissory note” and a "bad check" to turn a complex injustice into a vivid, relatable narrative that moved people:

… we have come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check – a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

2. Emotional volume control

Cicero and Quintilian both taught that the most powerful "pathetic" argument is frequently one that's understated.

A speaker who appears to be struggling to contain their own emotions often persuades more effectively than one who allows them to overflow. This "useful doubt" or feigned helplessness makes you appear honest rather than tricky.

When someone struggles to hold back their emotions—their voice cracking slightly or their pace slowing down—it creates a sense of sincerity. This is the "clumsy speaker" effect: an audience often mentalizes the case for a speaker who seems genuinely overwhelmed by the weight of their own message.

There are also times when the goal is not to inflame, but to calm.

You can use the passive voice—a staple of scientific writing—to intentionally lower the temperature of a conflict. By stating that "mistakes were made" rather than "you failed," you remove the bad actors, moving the audience away from defensive anger and toward collaborative problem-solving.

3. The bridge of desire

If the goal is commitment rather than simple agreement, logic (logos) and character (ethos) are usually insufficient. Logic can change a mind, but only desire can bridge that final gap to action.

All leaders hit this persuasion gap between people agreeing that an idea is good and actually being willing to do the work to implement it. The role of pathos in leadership is to bridge this chasm.

Pathos acknowledges that people are desire machines. We do not act on facts but on what we value and desire: whether that’s safety, status, a new product, the pride of belonging to an elite team, or a return to a golden past (nostalgia).

By matching your choice to the audience’s desire, you achieve "agreeability"—the state where the audience wants you to persuade them.

In the end, pathos is about being the most attuned. Leadership is "consensual" – rather than an exchange of information it's a marriage of minds in pursuit of a shared goal.

Leaders who lack pathos are like the mapmaker who forgets that people actually have to walk the terrain they’ve drawn. By relying solely on logic, you are treating your team as if they were calculators, not people.

The next time you find logic failing to move your team, don't simply add more information. Instead, pause and ask: "What’s their current emotional frame, and am I brave enough to address it?"

Related Articles on Pathos

Sources

- Aristotle, The Art of Rhetoric

- Jay Heinrichs, Thank You for Arguing

- Sam Leith, Words Like Loaded Pistols

- Nancy Duarte, Resonate: Present Visual Stories that Transform Audiences

- Frances Frei, Anne Morriss, Unleashed: The Unapologetic Leader's Guide to Empowering Everyone Around You

- https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/mlk01.asp

- Christof Rapp, "Aristotle’s Rhetoric," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy