Consider for a moment the last time you followed a directive at work that you privately questioned, or disliked. Why did you comply? Was it the fear of reprimand, or was it a more reflexive sense that the person giving the order had the right to do so? This difference between using force vs. the accepted right of someone to lead is the basis of what’s called “legitimate power”. It’s the power we give others because we believe they have a right to influence us, and we have a corresponding obligation to comply.

Much of the order in our professional lives is maintained by the quieter, more abstract force of legitimate power. But it also remains a misunderstood lever of leadership.

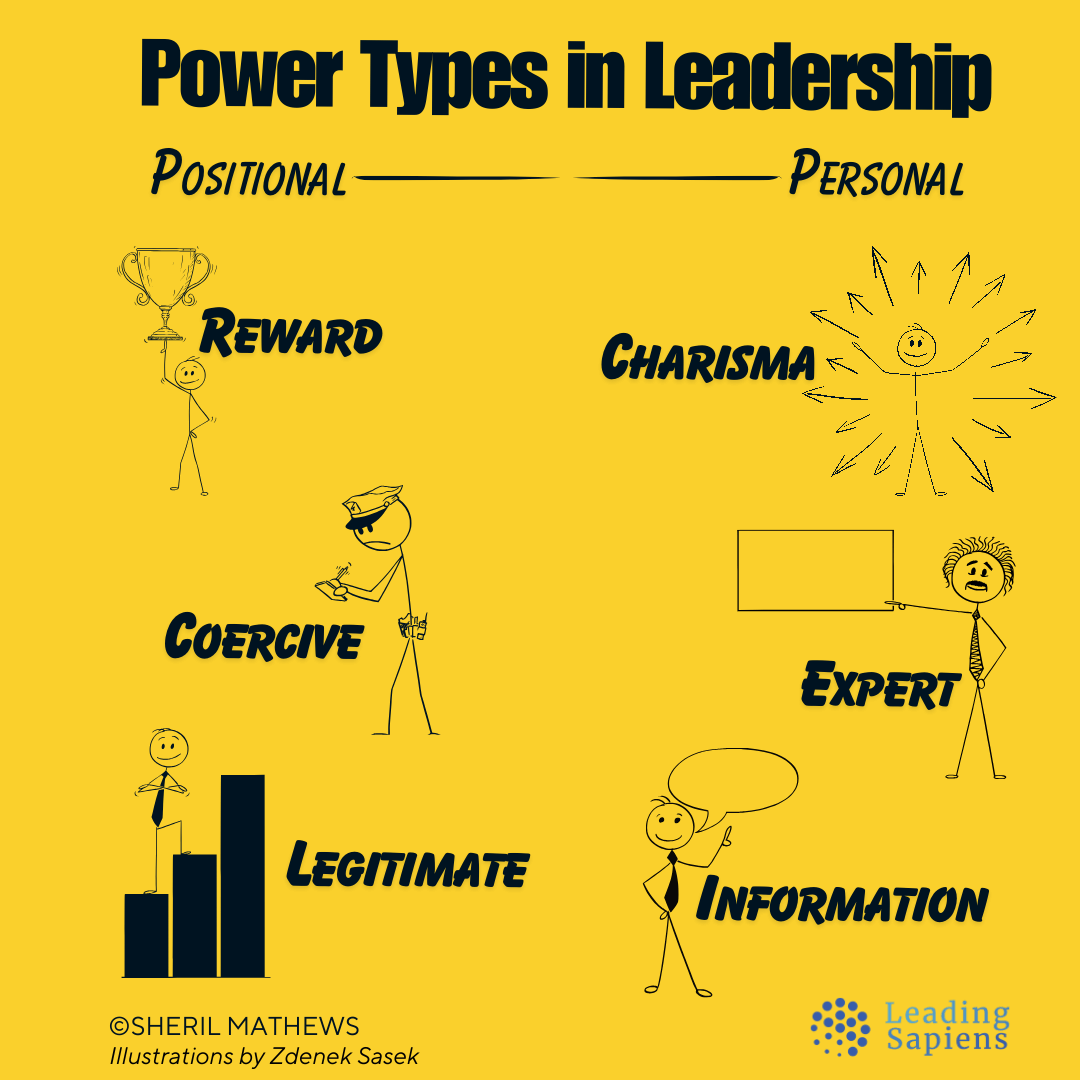

In this piece, I take a closer look at French and Raven’s original formulation of legitimate power (one of six types of power), and why many leaders misunderstand it.

What is Legitimate Power

In their foundational 1959 model, French and Raven defined legitimate power as that which "stems from the target’s accepting the right of the agent to require the change in behavior".

Put simply, legitimate power, or authority, is your ability to influence others’ actions because they accept your right to make decisions and thus feel a genuine obligation to follow your lead. You can often hear this power in the language used within an organization in terms such as "obliged," "should," "ought to," and "required".

We frequently follow instructions from individuals we neither particularly like nor personally respect. Consider the traffic policeman at a busy intersection. When he signals for traffic to stop, drivers typically obey without a second thought. They do not do so because they are enamored with his personality (referent power) or because they have performed a detailed cost-benefit analysis of his ability to fine them (coercive power) at that exact moment. They obey because they recognize the "rightness" of his role in that context.

In organizations, this is what allows a supervisor to assign tasks that employees might find tedious or disagreeable, yet which they fulfill because "that person is the boss".

A critical distinction of legitimate power is that it resides in the position or the office, rather than in the individual human being who happens to occupy it. It is "positional power". When a CEO retires, their legitimate power does not follow them into their garden; it remains vested in the role, waiting for the next incumbent to take it up. This creates the dynamic where an officeholder’s personal abilities can be quite mediocre, yet they are "robed in the mantle of high agency" simply by virtue of their title. You see this in the military, where rank is visibly displayed to ensure that a command is obeyed because of the "should" inherent in the social structure, regardless of whether the subordinates feel a personal connection to the officer.

As their research evolved, Raven further differentiated legitimate power to include more subtle forms that draw on universal social norms instead of just formal job titles. He identified three specific variants [2]:

Legitimate power of Reciprocity

We are socialized to follow the rule that one good turn deserves another. When someone does something beneficial for us, it creates a sense of obligation that makes us more likely to comply with their future requests.

In the workplace, this operates through a "I did that for you, so you should do this for me" sentiment. It acts as a lubricant for organizational cooperation, as it allows people to make the first move or a concession, confident that the social ledger will eventually be balanced. This power is so potent that it can even obligate us to return favors from people we don't particularly like or to repay a small favor with a much larger one just to relieve the psychological burden of being "indebted".

Robert Cialdini later popularized this notion through his "Influence" framework.

Legitimate power of Equity

This form of power allows someone to influence you because they've "worked hard and suffered". Their sacrifice creates a perceived moral right to ask for a compensatory action or concession.

It relies on our internal sense of justice — the belief that the benefits and burdens in a work relationship should be fairly and equitably distributed. When we see someone paying a high personal cost for the group, we acknowledge their legitimate right to be "repaid" or supported in return. Unlike reciprocity, which is about returning a favor, equity is about balancing the scales of effort. It provides a platform for those who have shouldered the heaviest loads to exert influence based on the merit of their contribution.

Legitimate power of Responsibility

Often called the "power of the powerless," this norm suggests that we have an inherent obligation to help those who are dependent upon us or who cannot help themselves.

It shifts the focus from what we have to do for a boss to what we should do for someone who is counting on us. A manager or team lead might invoke this power by saying, “I’m really depending on you to do this for me”. By highlighting their dependence on your specific expertise or effort, they are activating your internalized sense of social responsibility. Because this power is based on the person’s own value system, it doesn't require the threat of punishment to be effective. Instead, it works through the willing acceptance of a shared duty to the collective success of the team.

The Three Pillars of Legitimacy

Legitimate power is not a one-sided imposition of will. It’s a relational agreement where the subordinate "ratifies" the status of the superior through their commitment and the quality of their decisions. Unlike reward or coercive power—it doesn’t require ongoing surveillance.

Since legitimate power is not a thing you possess but a relation that others recognize, where does this recognition originate?

The sources of legitimacy generally fall into three categories [1]:

(1) Prevailing cultural values. In many societies, specific attributes such as age, gender, or high-status lineage inherently grant a person the right to influence others. In organizations, this shows up as beliefs in the sanctity of the hierarchy or the specialized value of certain functional roles. For example, the accountant's involvement in financial matters or the engineer’s prerogative in technical decisions.

(2) Accepted social structure. This is the most common form in modern work life. When accepting a role in a company, we are effectively entering a social contract that validates the hierarchical structure, thereby granting legitimate power to our designated managers.

(3) Designation by a sovereign entity. Legitimacy can also be transferred. A committee chairperson or an elected official holds power because they've been designated as the representative of a larger, powerful group that the community already recognizes.

You can see parallels between French-Raven’s formulation and that of Max Weber — the foundational voice on institutional power. Weber identified three types of rule that makes obedience probable [4]:

Rational-legal authority. This is the hallmark of the modern bureaucracy. It's founded on a belief in the legality of enacted rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands. We obey the "files" and the "functions" because we believe the system itself is rational and impartial.

Traditional authority. This power is rooted in the sense of the sacredness of long-standing traditions. It's the power of the king or the tribal elder, where legitimacy is granted because "that’s how things have always been".

Charismatic authority. This is the most unstable yet potent form that’s based on a person’s extraordinary personal qualities. Followers comply out of identification with or devotion to the leader’s perceived heroic or exemplary character. While not the same, referent power is more durable form of this power.

How Leaders Misunderstand Legitimate Power

A common misunderstanding in modern leadership is the belief that legitimate power—the authority vested in a formal role—is synonymous with your capacity to get things done.

We treat promotions as if they were an upgrade, like going from analog to digital. The assumption is that when you get a title, it comes with the corresponding amount of influence.

But in reality, being at the top of an org chart is no guarantee that a team will follow your lead. If you have to rely solely on your formal position to command action, you aren't demonstrating strength but exposing weakness.

Legitimate power is effectively a social contract. It exists only to the extent that others consent to being controlled. When you step into a role — whether as a manager, a doctor, or a pilot — you are robed in an impersonal power that precedes your arrival and continues after your departure. Your "office" provides a mantle of agency that allows you to decide, appoint, and execute, not because of who you are, but because of the position you hold.

Let’s look at some common stumbling blocks around legitimate power.

Authority is not power

The first misunderstanding is the conflation of authority with power. Authority is merely the formal right to give orders based on a title or rank, whereas power is the actual capacity to influence behavior and outcomes. You can hold the highest office and possess absolute formal authority, yet find yourself "in office but not in power" — your commands echo in an empty chamber because you lack the social capital to make them stick.

This power gap is inherent in almost every leadership job because modern leadership requires the cooperation of people over whom you have no explicit control, such as peers, superiors, and external stakeholders. Managers often find themselves in the frustrating position of being responsible for outcomes while lacking the unilateral power to compel necessary actions from others.

True power is relational; it exists only in the context of a relationship and depends entirely on the extent to which others need you for rewards or to avoid penalties.

In this sense, authority is conceded from the bottom up. It’s a mandate granted by others that allows a disagreement to dissolve in favor of the leader’s direction. When we wholeheartedly enlist in someone’s cause, we effectively delegate a much stronger kind of power to them than their title alone could ever provide.

Legitimacy comes from below

We typically visualize authority as a force that flows from the top of the hierarchy to the bottom. But if people do not consent to be led, the leader has no authority, regardless of the size of their desk or the prestige of their title.

When people comply with a boss they don’t respect, it creates an atmosphere of resentment and minimal effort. This is the "cost of weakness"—the gap between how much power a leader is perceived to have and what they can actually achieve [6].

We legitimize the status quo because questioning the natural order of the hierarchy is cognitively taxing and socially risky [7]. We carry our bosses around in our heads, following their lead to avoid the psychic stress of total autonomy.

The limits of "because I said so"

A common mistake among new or insecure managers is relying too heavily on "position power" to gain results. While legitimate power can ensure compliance—getting people to follow basic rules and procedures—it is notoriously poor at generating commitment. Commitment occurs when someone wants to execute a decision, which typically stems from expert power or referent power rather than formal rank.

Over-reliance on using force when other tactics fail creates "docile bodies" who perform the minimum required while withholding the creativity and initiative that organizations need to survive.

Ironically, the more someone feels the need to demonstrate they are powerful by pulling rank, the less real power they likely possess.

Power-with vs. power-over

There’s a paradox at the heart of legitimate power: to increase your power, you must delegate it. Mary Parker Follett distinguished between "power-over" (coercive and prohibitive) and "power-with" (coactive and facilitative).

True legitimate power is facilitative. It's the "power to" achieve something in concert with others. When leaders use their position to solve systemic problems rather than just personal ones, their status and legitimacy rise. Conversely, the more leaders have to use bullying or intimidation, the less real power they actually possess. Direct intervention and force are usually signs that legitimate authority has failed or slipping.

Ultimately, legitimate power is not a right but a fragile trust. It’s the part you play in someone else’s story, and that’s only sustainable as long as it adds value to the collective whole.

Power is simply a medium through which we relate to each other. The most powerful leader is the one who needs to use force the least because they have built a system of authority so grounded in mutual benefit and shared vision that their will is naturally accepted as the group's own.

Realizing that you likely have more power than you think — but less than your title implies — is the first step toward using it well.

Related Articles on Power

Sources

- French, J. R. P., Jr., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power.

- Raven, B. H. (1993). The bases of power: Origins and recent developments.

- Huczynski, A. (2004). Influencing within organizations

- Clegg, S. R., & Haugaard, M. (Eds.). (2009). The SAGE handbook of power.

- Clegg, S. R., Courpasson, D., & Phillips, N. X. (2006). Power and organizations.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1976). Ambiguity and choice in organizations.

- Kleiner, A. (2003). Who really matters: The core group theory of power.