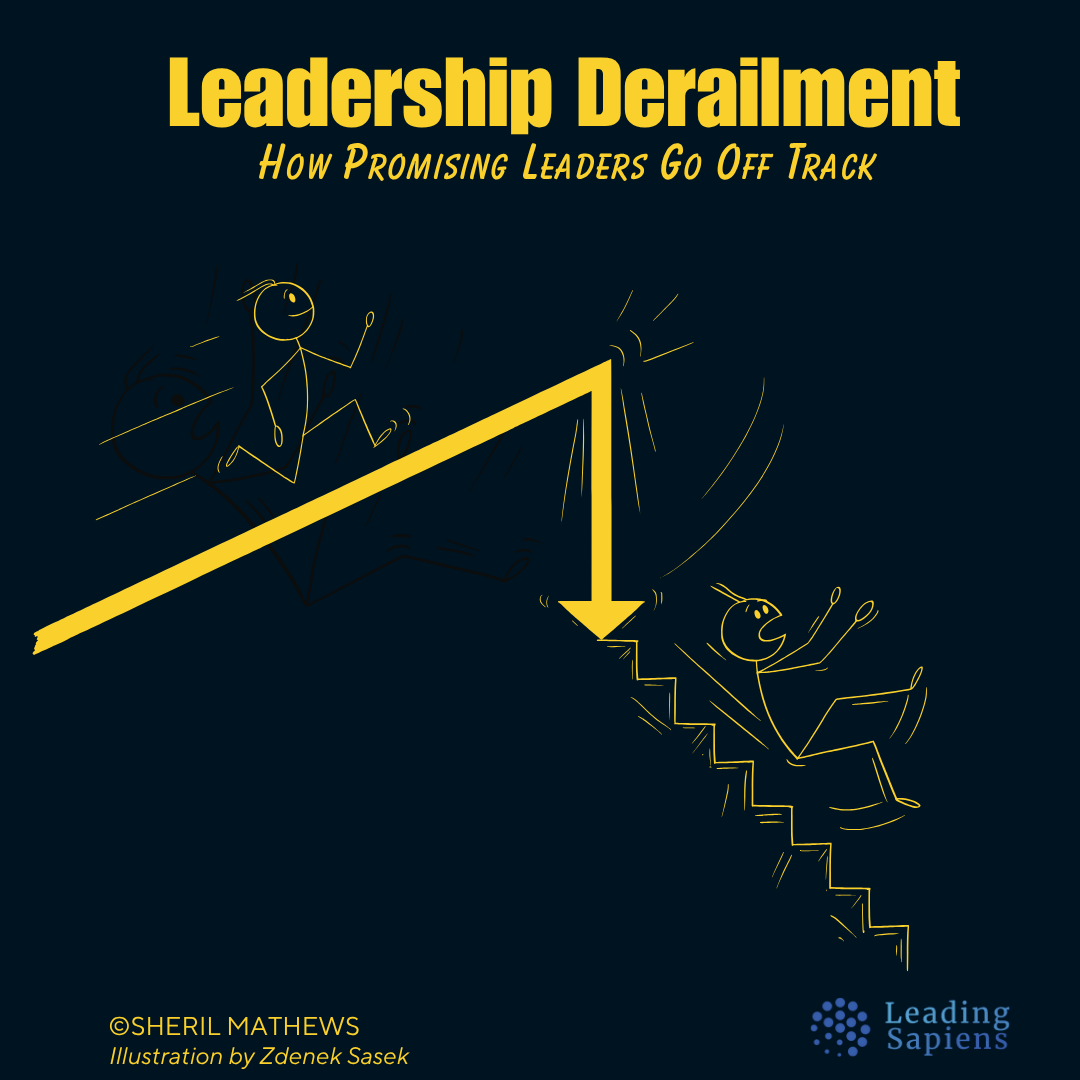

It's easy to assume that leaders derail due to obvious flaws like poor judgment, unchecked ego, toxic behavior. But that's not usually the case. Many derail because they lean too hard on the very strengths that got them there.

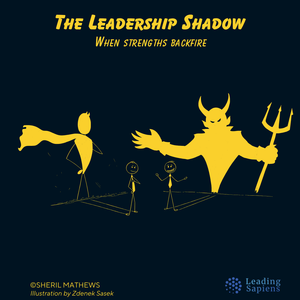

Like a rope fraying one thread at a time, this happens slowly and invisibly. They overuse a trusted way of leading until they can’t see what they've lost, and become narrower, less adaptable, and more disconnected. Leadership, given enough time, casts a shadow that colors how others see you, and ultimately, how you see yourself.

Understanding your leadership shadow is essential for survival. This piece maps that hidden territory.

From managerial roles to leadership shadows

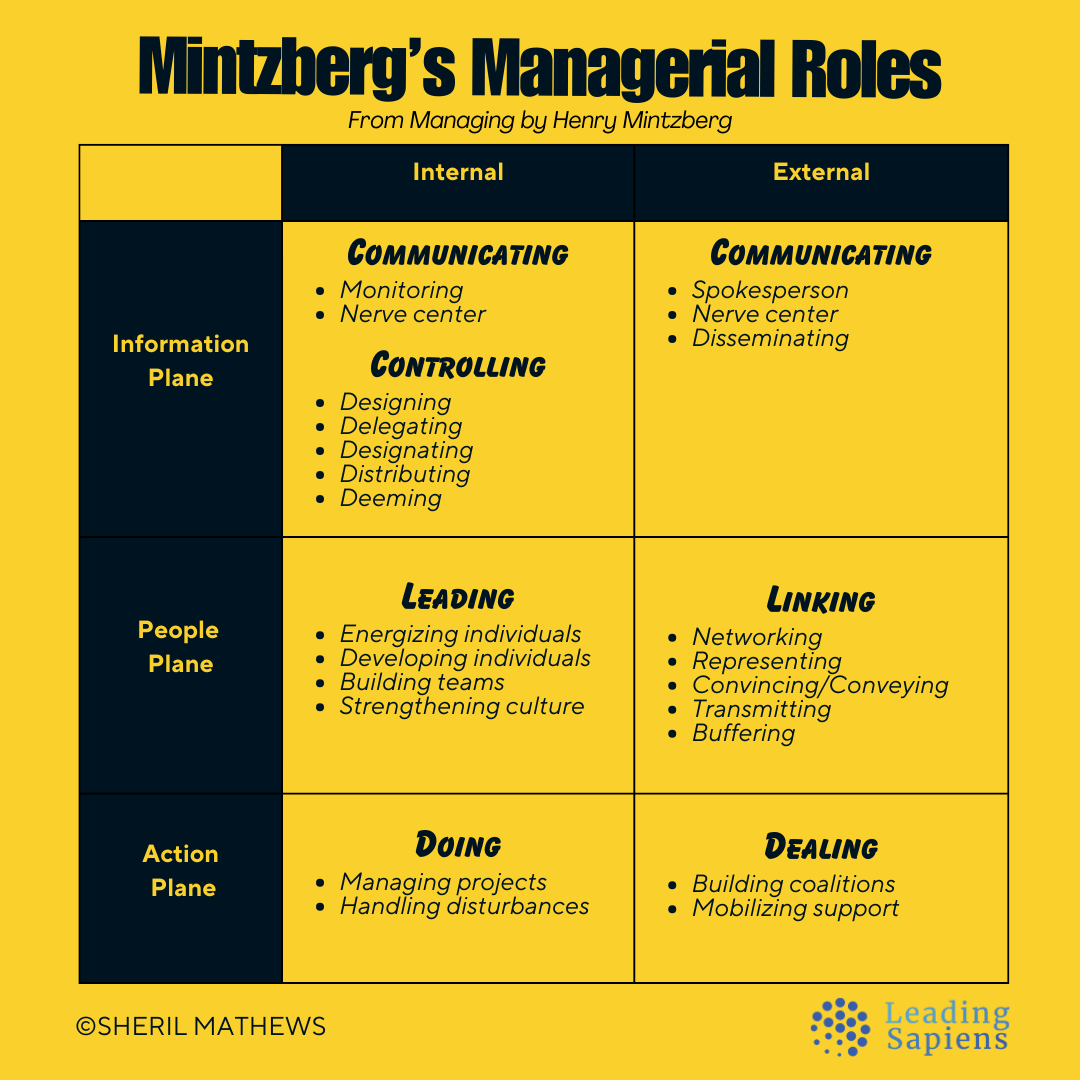

Henry Mintzberg famously mapped out ten managerial roles—everything from figurehead to negotiator to disturbance handler—based on close observation of how executives actually spend their time. It was one of the first attempts to ground leadership in what leaders do, not just what they intend.

However, Mintzberg's observations didn't fully capture what happens beneath the surface. This is where Erik de Haan and Anthony Kasozi pick up the thread in The Leadership Shadow: How to Recognize and Avoid Derailment, Hubris and Overdrive.

They highlight how:

- Roles not only organize behavior, they also shape identity.

- Every leadership function privileges some part of you and suppresses something else.

- Leadership roles often distort who you become.

Every time you emphasize one aspect of yourself to meet leadership demands — decisiveness, vision, steadiness — another part gets pushed aside. Over time, this distortion hardens and conflates the role you play with who you are.

What you regularly express is only half the story. The other half—the parts you've unconsciously put away—becomes your shadow that quietly builds in the background.

The result isn't immediately obvious. You're still hitting targets and respected. But underneath, the very things that made you successful start limiting you.

While Mintzberg showed the visible architecture of managerial work, De Haan and Kasozi reveal what's underneath that structure: emotional cost, cognitive drift, and identity creep that comes with being "the leader."

Three core modes of leading

De Haan and Kasozi distill leadership into three core functions, or “modes of contribution” along with the illusions (shadow effects) these create. These are patterns that emerge based on how you habitually lead:

1. Doing (Supporting): You make things happen, facilitate, decide, allocate, and push forward.

2. Thinking (Inspiring): You set direction, generate insight, synthesize complexity, articulate what’s next.

3. Feeling (Containing): You absorb emotional strain, hold space, offer empathy, and steady the group.

Each of these are vital and none is superior. But when one becomes your dominant posture, it starts to distort. Not how you perform, but what you no longer perceive.

Every strength casts a shadow

Leadership doesn’t just bring your strengths into the light. It also casts parts of you into the shadow. Here’s how each function creates its own blind spot:

1. Doing → Illusion of Omnipotence

If your strength is action, decisiveness, and delivery, you begin to see yourself as the one who makes things happen. And when that’s reinforced enough times, it becomes difficult to admit when you can’t.

You suppress your own needs for support, collaboration, or pause, and instinctively fill gaps before others can step in. You become the leader who always carries the load — and quietly resents others for not doing the same.

Over time, this creates a kind of functional isolation. People expect you to act, not ask. And you expect the same of yourself.

This is the illusion of omnipotence, not out of arrogance, but over-functioning. It's the belief that your value lies in what you do, and if you stop doing, you stop leading.

2. Thinking → Illusion of Infallibility

If your primary strength is sensemaking — connecting dots, spotting trends, offering insight — you may start to unconsciously identify with your ideas. You the one with the plan and who offers clarity.

But clarity can become rigidity. You stop noticing when your framing is incomplete. You explain instead of listening, and analyze when someone needed empathy. Thinking sharpens, but curiosity dulls.

Illusion of infallibility doesn’t mean you think you’re always right. It means you’ve stopped noticing the moments when you’re not. You've become immune to correction because others have learned that disagreement rarely changes your mind.

3. Feeling → Illusion of Invulnerability

If your default mode is emotional containment — absorbing others’ distress, staying calm in crisis, showing empathy — people see you as a source of steadiness. You’re the one who holds the space.

But if you over-identify with this role, you begin to ignore your own needs. You become so used to listening that you stop expressing. Others feel safe with you but rarely intimate.

You start to believe you don’t get rattled. And when you do, you hide it even from yourself. With time, you flatten emotionally as a way for self-protection.

This is the illusion of invulnerability: the unspoken belief that you don’t need care, because you’re the one giving it.

Why this matters

Derailment rarely announces itself and isn’t typically caused by dramatic flaws. It’s caused by unexamined loyalty to a single way of leading.

It builds through overuse, distortion, and self-narrowing, because you haven’t adjusted the role you’ve been living in.

- The doer burns out, surrounded by passive teams.

- The thinker loses influence, dismissed as detached or arrogant.

- The feeler disappears into quiet resentment, wondering why no one checks in on them.

Most leaders don’t burn out from weakness but from unexamined strength.

The damage manifests as disconnection — from your full range of abilities, diverse perspectives, and evolving team needs. As others adapt to your blind spots, feedback diminishes and presence becomes rigid.

This is why the shadow matters. Not as a psychological metaphor, but as operational reality. Ignoring vulnerability or doubt doesn't just limit personal growth; it constrains your entire leadership field.

Examining these dynamics is a vital way to sustain leadership effectiveness and prevent the invisible drift toward derailment. By recognizing these patterns early, leaders can reclaim their full range and maintain the flexibility essential for long-term success.

What to do about it

You don’t need a psychological deep dive to work with this. Just stop assuming that your best mode is the only one. Three simple steps can help surface the shadow:

1. Name your dominant mode

- Which of the three functions — doing, thinking, or feeling — do you rely on most? What do others instinctively come to you for?

- Then ask: What don’t they come to me for? What do I avoid? What situations do I feel ill-equipped to handle?

- That’s your edge. And also your shadow.

2. Track what irritates you

- Irritation is often unacknowledged projection. The behaviors that bother you in others — neediness, indecision, emotionality — often point to parts of yourself you’ve disowned.

- What we can’t stand is often what we fear becoming.

3. Loosen the identity grip on your primary mode

The most insidious trap isn’t over-functioning but too much self-identifying with the function.

- “I’m the one who gets things done.”

- “I’m the one who sees the big picture.”

- “I’m the one who stays grounded.”

These are roles. Not realities. The longer you believe them, the less room you have to grow.

The goal isn’t balance but integration. Leadership range comes not from adding skills, but from reclaiming the parts you’ve stopped allowing.

In closing

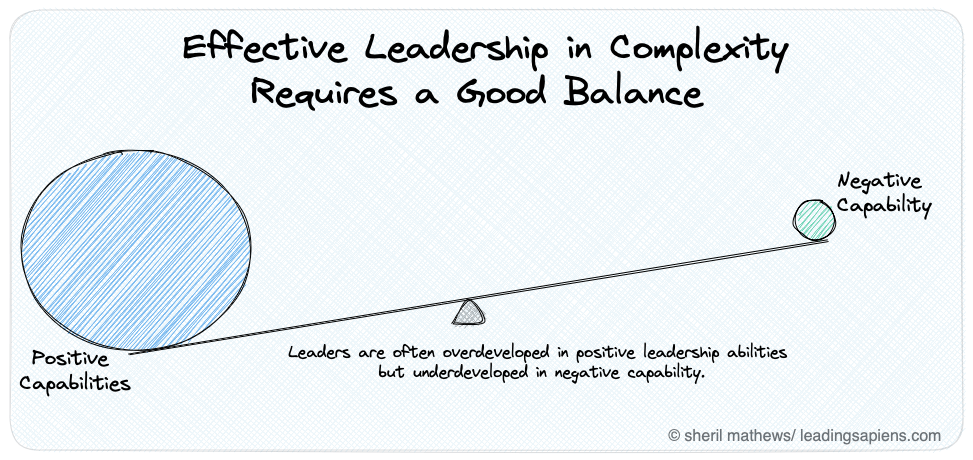

Mintzberg showed us the architecture of what leaders do. De Haan and Kasozi invite us to ask what those roles do to us. This is a deeper aspect of leadership which goes beyond execution by staying aware of the costs in order to stay in the long game.

You don’t need to do less of what you’re great at. You just need to notice how it's changing you. The longer you lead, the more you need to ask: What has my role made me forget about myself?

Related reading

Sources and references

- De Haan, E., & Kasozi, A. (2014). The Leadership Shadow: How to Recognize and Avoid Derailment, Hubris and Overdrive.

- Lombardo, Michael M., et al. “Explanations of Success and Derailment in Upper-Level Management Positions.” Journal of Business and Psychology. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25092138.

- McCall, M. W., Jr., & Lombardo, M. M. (1983). Off the track: Why and how successful executives get derailed (Technical Report No. 21). Center for Creative Leadership. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.1983.1083

- Development Dimensions International. "Global Leadership Forecast."

- Development Dimensions International. "Leadership Transitions Report."