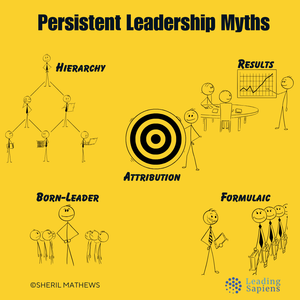

Why do organizations repeat the same leadership mistakes despite research showing they don't work? A key reason is pervasive leadership myths.

When Boeing's board asked CEO Dave Calhoun to step down, it followed a familiar script. New leader, fresh start, problems solved. It was supposed to restore confidence. But the assumption — that company issues stem from the person at the top — reveals something deeper about how we think about leadership.

This assumption persists not because it's true, but because it's psychologically irresistible. Leadership myths survive not on evidence, but because they offer simple explanations for complex outcomes and make us feel like someone is in control.

It feels like logic, but it's actually mythology. These leadership myths don't just distort judgment; they erode trust and set up leaders and organizations for failure.

The most dangerous part is we don't call them myths. They masquerade as best practices, conventional wisdom, and common sense.

The Attribution Myth (leaders cause results)

This is the myth we most want to believe: if something goes spectacularly right—or disastrously wrong—it’s because of the leader. It’s clean, satisfying, and emotionally appealing.

But as General Stanley McChrystal argues in Leaders: Myth and Reality, this logic rarely matches reality. He calls it the attribution myth: our tendency to assign outcomes to a single leader, ignoring the web of circumstances, systems, and collective efforts involved.

McChrystal’s central insight is that we confuse leadership with causation. If someone presided over success, we assume they caused it. But that’s post hoc reasoning, not causality.

We want to believe that someone was in charge, deserving credit or blame. It gives us closure. But it’s often a fiction.

This isn’t harmless. In organizations, the attribution myth simplifies what should be a deeper diagnostic. When a team wins a big client or ships a product on time, the leader is celebrated. When a project fails, the same individual may be quietly replaced. But that lens blocks better questions: What conditions enabled the success? What invisible collective efforts contributed to it? What systemic issues were ignored in the failure?

The attribution myth feeds unrealistic expectations. It pressures leaders to over-control, over-own, and over-perform, because the narrative says it’s all on them. It also stupefies organizational memory. We forget the role of timing, policy changes, competitor missteps, or collective decisions. We cling to the image of the singular leader steering the ship, even when the tides influenced the outcome more than the captain.

Trust in leadership erodes when this myth breaks. When success doesn’t repeat, or when a supposedly brilliant leader stumbles, people feel betrayed. Not because the leader lied, but because the story we told about them was a lie. We set them up as the author of results, then punish them when reality reasserts its complexity.

To lead well and build healthy organizations, the attribution myth needs to be retired. They have to stop treating leadership as a solitary act. The real work is collective, contextual, and interdependent.

Anything less is just a better-written fairy tale.

The Formulaic Myth (leadership can be codified)

A persistent myth in modern leadership is that it can be broken down into a repeatable formula, a set of principles or behaviors, that if followed will predictably produce great outcomes.

McChrystal calls this the formulaic myth. It’s the belief that leadership can be codified, decontextualized, and transferred wholesale from one situation to another.

This myth feeds our need for certainty. It reassures us that if we find the right model, checklist, or personality profile, we can manufacture good leadership at scale. That’s why bookstores are full of leadership secrets from warriors, presidents, and CEOs.

We take isolated stories and treat them like templates, often ignoring their actual complexity.

Leadership development becomes about ticking boxes: presence, communication, decisiveness, authenticity. Managers follow frameworks or off-the-shelf trainings that promise to mold someone into a 'strategic communicator' or 'servant leader.' Although reassuringly structured, these programs reinforce imitation and posture instead of inquiry and presence.

Real leadership rarely fits into templates. It's not a clean sequence but iterative, relational, and context-sensitive.

In practice, formulaic thinking creates fragile leaders. People who’ve mastered the language and posture of leadership but haven’t learned to read context, adapt their stance, or navigate paradox. When the situation changes, and it always does, they cling to the script even when it no longer fits.

It creates a false meritocracy. Those who match the formula — extroverted, verbally polished, confident under pressure — rise quickly, not because they’re better leaders but because they fit the costume. Leadership becomes a performance rather than a responsibility.

What organizations need is not a formula but a set of practices. One that is alive to feedback, sensitive to the system, and built on evolving relationships. Leadership isn't a thing you acquire but a thing you do, repeatedly, in changing circumstances.

The Results Myth (good results = good leadership)

This myth uses outcomes to measure leadership effectiveness. If the numbers are good, the leader must be good. It's seductive because it appears objective. Success is success, right?

But the results myth conflates correlation with causation differently than attribution. While attribution assumes leaders cause outcomes, the results myth works backward by using outcomes to evaluate leadership quality after the fact. Good results become retroactive proof of good leadership, regardless of what drove those results.

Organizations that buy into the results myth mistake lucky timing for skillful leadership. What other factors were at play? Market timing, favorable conditions, inherited momentum, or lucky breaks can all masquerade as effectiveness. When things are going well, the myth kicks in hardest.

The real problem is that it skips critical reflection by creating false positives. Leaders presiding over a good cycle are seen as visionaries. The organization then tries to replicate what they did even if those actions were peripheral to the actual outcome. Meanwhile, teams facing real constraints or ambiguous challenges are seen as underperforming, even if the work was more skillful.

This myth also invites complacency. Success insulates leaders from scrutiny, discourages dissent, and inhibits learning. People don’t challenge the leader’s assumptions or decisions because the scoreboard looks good. But as seen in countless corporate flameouts, success is often the worst time to stop asking questions. That’s when feedback disappears and invisible risk accumulates.

To break the results myth, separate outcome from process. Organizations need evaluation systems that value how results were achieved, not just what was achieved. Was the team set up for long-term success? Were tradeoffs acknowledged? Did we learn anything repeatable or just get lucky?

Effective leadership can’t be measured solely by good outcomes. It must be measured by the quality of decisions, the integrity of process, and the system’s long-term health.

Otherwise, we’re not evaluating leadership, just betting on a hot streak.

The Hierarchy Myth (leadership comes from above)

This myth is so embedded in organizational life that we barely notice it.

The leader is the face on the strategy deck, the voice in the all-hands meeting, and the name on every major decision. It’s easy to assume that leadership flows from the top down. But this assumption collapses under scrutiny.

Much of what passes for leadership in organizations doesn’t come from the top. It happens in peer interactions, cross-functional problem-solving, and informal coalitions. These are essential but rarely seen as leadership. Because the myth tells you to look upward.

The idea of a singular leader misrepresents how complex systems function.

Most organizational challenges today don’t yield to top-down directives. They require distributed ownership and iterative adaptation. That work is messy, collaborative, and often invisible. And it doesn’t show up on an org chart.

The danger lies not in hierarchy itself, but the assumption that authority equals insight. When the myth is in play, those lower in the structure defer rather than contribute. Risk is avoided rather than shared, and responsibility is offloaded upward. Soon, the organization becomes reliant on a narrow band of people to think and initiate.

This places an unsustainable burden on the top person, who is expected to be visionary, decisive, and omniscient. But no one sees clearly from a distance. The farther you are from the front lines, the more abstract your understanding. If people stop speaking up or surfacing concerns because they assume leadership belongs elsewhere, the organization loses its edge.

We need to stop equating leadership with role and start recognizing it as a function. Leadership is what happens when someone steps in to clarify, connect, or mobilize others, regardless of title.

The real question isn’t who the leader is. It’s whether leadership is happening where it’s needed.

The Born-Leader Myth

This is the oldest and most persistent leadership myth.

It's the idea that some people are born to lead, while others are not. That leadership is an innate trait, like height or eye color. It's a belief baked into everyday language: "natural leader," "born for this," "has it in their blood." It's embedded in how organizations assess talent.

The myth endures because it’s intuitive. We see someone who speaks confidently or handles pressure well, and we assume those traits have always been there. But that intuition is shaped more by our default mental models than actual evidence.

Researchers call these "implicit leadership theories": unconscious templates of what a leader looks and sounds like, often skewed toward charisma, extroversion, dominance, and certainty.

We overvalue early bloomers and undervalue those who develop through experience, reflection, and deliberate practice. Talent development gets distorted. High-potential lists skew toward those with polished traits. Mentorship opportunities go to those who 'look the part.'

What looks like innate leadership is often the result of exposure, feedback, and practice. What looks like hesitation or quietude is often the early stage of a different kind of leadership emerging, rooted in observation and considered action.

Organizations that cling to the born-leader myth end up narrowing their leadership pipeline. They build echo chambers around a particular style and miss out on the diverse approaches that complex systems require.

To move beyond this myth, we need to treat leadership as a developmental process, not a personal trait. That means designing systems that surface emerging leadership in all its forms. It means training leaders to recognize potential not just in finished products, but in early signals.

It means understanding that enduring leadership grows quietly, shaped by practice, reflection, and context.

Leadership myths persist because they're easier than the truth. The truth is that leadership in complex systems is messy, collective, and often invisible. It happens in the spaces between formal authority and actual influence. It emerges from relationships, context, and countless small decisions made by people throughout an organization.

Ironically, clinging to these myths makes leadership harder, not easier. We set up leaders for impossible expectations and organizations for systematic disappointment. We create cycles where "heroic" individuals burn out, teams become dependent instead of capable, and real leadership goes unrecognized and undeveloped.

Breaking free from these myths is about developing a mature relationship with uncertainty, complexity, and collective action. It's about systems that can adapt, learn, and respond without requiring a singular genius at the helm.

In increasing complexity, organizations that thrive will be those that acknowledge the mundane reality of how change happens and build their leadership development around that truth instead of the myths that make us feel better.

Next, I'll explore what real leadership looks like when we stop pretending it's something it's not.

Sources and further reading

- McChrystal, Stanley, et al. Leaders: Myth and Reality.

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey. Leadership BS: Fixing Workplaces and Careers One Truth at a Time.

- Eagly, Alice H., & Carli, Linda L. Through the Labyrinth: The Truth About How Women Become Leaders.

- Center for Creative Leadership. “High-Potential Talent: A View from Inside the Leadership Pipeline”