The executive stared out the window, shell-shocked and feeling blindsided. Her boss had just asked for her resignation. How did it come to this? This scene plays out in organizations more often than we think. Leadership derailment — when a once-promising leader stumbles and falls — isn't limited to the C-suite. It can happen to team leaders, middle managers, and senior executives alike.

Leadership derailment is insidious yet avoidable. Research shows clear patterns in how promising leaders falter. In this piece, I examine:

- How successful traits become career-ending liabilities.

- Why derailment goes unnoticed until it's too late.

- Organizational structures that enable derailment.

- How to recognize early warning signs.

- Ways to prevent derailment.

The exec prided herself on identifying and driving key initiatives, which had propelled her rapid rise. But now, those strengths had become liabilities. Her refusal to adapt to changing dynamics and dismissal of dissenting voices had left her division struggling.

As she packed her desk, she wondered: How had her greatest assets contributed to her downfall?

The Hidden Nature of Derailment

Derailment is less cataclysmic and more like a slow drift. Leaders continue doing what made them successful, unaware that the context has changed, or that they’ve changed.

But those closest to them can feel it. The direct reports who once thrived under their intensity now flinch. Collaborators walk on eggshells. Spouses and partners notice the volatility long before HR does.

This asymmetry is structural. As leaders gain seniority, two things happen:

- First, they gain discretion: more freedom to decide, shape, and interpret.

- Second, they receive less feedback: fewer honest signals, less pushback, and more filtered responses. What’s reinforced is confidence, but at the price of calibration.

The outward signs still look like high-functioning leadership. What’s happening underneath is harder to see:

- Relational weariness sets in.

- The team stops offering bad news.

- The leader over-relies on instinct.

- The system stops pushing back.

These early signs rarely appear on the radar of peers or bosses, and certainly not in formal assessments. Derailment is more visible in the close-in relationships. And even then, calling it out comes with risk. Most derailments unfold in environments where honesty is expensive.

Initially, the suspect traits are rewarded. The driven manager gets results, or the intense operator fixes problems. But over time, the same behavior that once stood out begins to wear down teams and isolate the leader.

It feels sudden because the signals were hidden behind the leader’s familiar habits, normalized by success, and reinforced by silence.

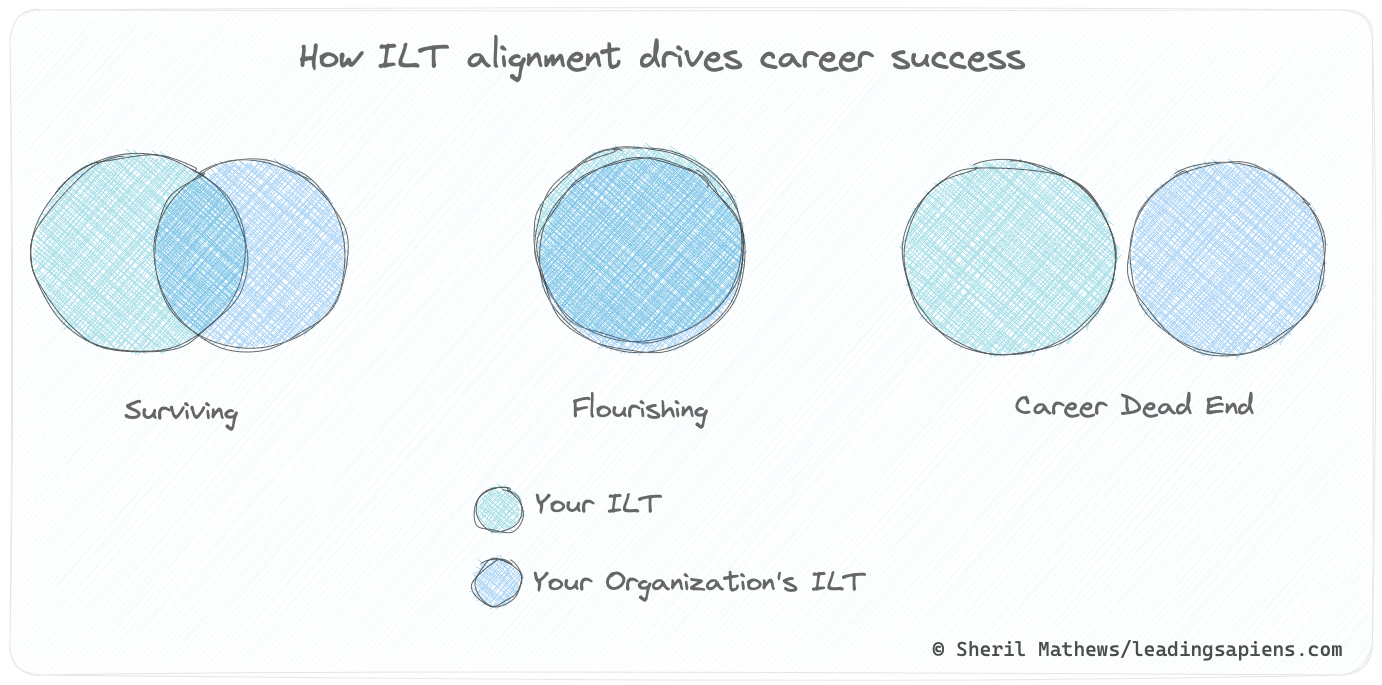

This makes derailment harder to prevent. Instead of a lack of skills or gaps, it’s about slowly becoming misaligned — with the role, context, others, and oneself — and not catching it in time.

What Goes Wrong

When leaders fail, it’s tempting to blame obvious deficiencies like poor communication or weak execution. But the research on leadership derailment tells a different story.

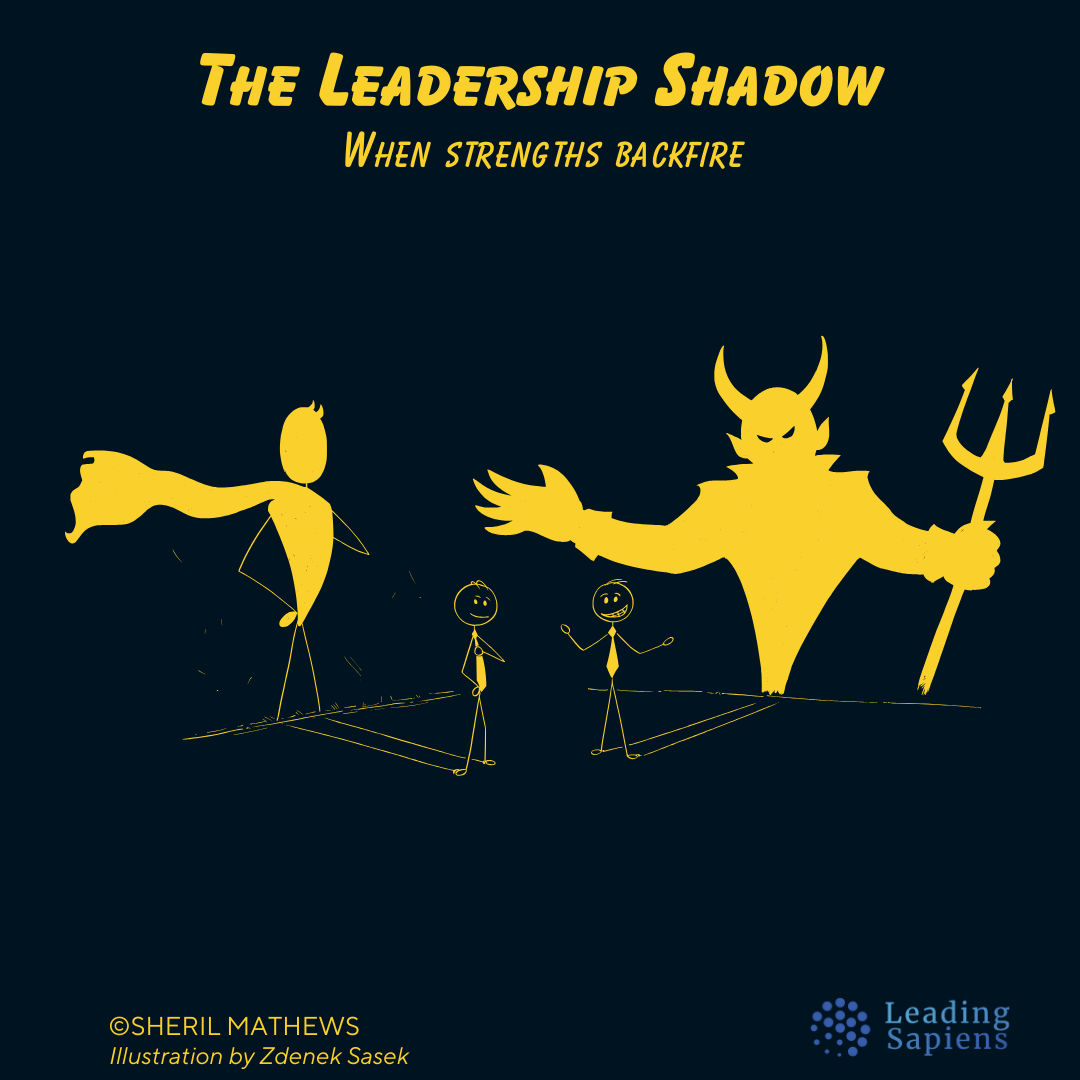

Most derailments aren’t about lack of talent, but misapplied talent. Strengths that no longer fit the context, or that have stopped evolving while everything else moves on.

Across multiple field studies, consistent patterns emerge. [1,11] And none are technical. They’re relational, behavioral, and cumulative:

- Breakdown in interpersonal relationships. Described as arrogance, manipulation, aloofness, or being a lone wolf who can’t engage.

- Failure to deliver results. Not from lack of effort, but from overpromising, micromanaging, or being overwhelmed by complexity.

- Inability to lead or sustain a team. Usually because the leader burns people out, undervalues contributions, or substitutes control for trust.

- Difficulty adapting to change. A rigid mindset, refusal to shift, and over-reliance on past formulas.

- Overly narrow focus. Technically deep but organizationally shallow; unable to widen the frame beyond their function.

These aren’t the typical sins of junior employees. These are missteps of people who’ve succeeded long enough to be trusted with more and who continue applying the same strengths until they backfire.

Surprisingly, derailment doesn’t correlate with low intelligence or poor social skills. In fact, some studies show the opposite: the derailed group tests higher in perceived charisma and cognitive ability than their peers. The difference is their inability or unwillingness to adjust when context demands it.

Under pressure, leaders lean harder on what has always worked:

- The perfectionist doubles down on details.

- The visionary disconnects from reality.

- The relationship builder avoids conflict.

- The high-achiever starts hoarding control.

These leadership missteps aren't abnormal or deviant. They're common and expected patterns. Leaders often can't see these issues in themselves because the actions feel familiar and have worked well in the past. It seems like business as usual.

But context doesn’t stay still; organizations evolve and roles shift. When leaders don’t evolve, what was once a strength becomes a liability. While not overnight, it happens incrementally until performance suffers and recovery becomes harder.

It’s an absence of calibration, not a lack of skill.

The Architecture of Derailment

A clear predictor of derailment isn’t skill gaps but personality in overdrive. As Dotlich and Cairo observed, leaders derail because of habitual tendencies that turn toxic under pressure. These aren’t random. They’re repeatable, recognizable, and — for many — entirely familiar:

- The achiever becomes compulsive.

- The collaborator becomes approval-seeking.

- The challenger becomes volatile.

- The detail-oriented leader becomes paralyzed by caution.

These are deep behavioral grooves forged by success and reinforced by feedback loops. Under stress, they stop being strategic preferences and become hardwired, unconscious reflexes.

This is why the best derailment frameworks focus not just on skills, but on character patterns. The Hogan Development Survey maps “dark side” traits that emerge under strain: arrogance, melodrama, aloofness, perfectionism, mistrust.

Not all of these are career-ending. What matters is context: the role’s requirements, others’ experiences, and how long it goes unexamined.

But personality alone isn’t the problem. It’s what happens when it operates in conditions of wide discretion.

As leaders advance, they gain more autonomy. But discretion is a double-edged tool. It’s how they make a difference but also lose the ability to self-correct. As de Haan and Hogan pointed out, discretion without feedback becomes distortion. The more leeway a leader has, the more their personality fills the vacuum.

It’s why leaders in high-discretion environments — startups, tech, creative industries, founder-led firms — are more vulnerable to derailment, as they are less likely to push back. In weak cultures, with limited oversight, the guardrails disappear. A leader’s inner tendencies become the operating system.

Without counterweights — peer feedback, grounded data, trusted dissent — strengths keep scaling, and eventually distorting. Derailment is rarely about bad intentions. It’s about unchecked tendencies gaining too much room.

Systemic Factors Causing Derailment

It’s easy to view leadership derailment as a personal failure. But most derailments are co-produced; shaped by the organizational systems that elevate, tolerate, or misread the person.

Often, the problem isn’t the leader’s personality but the environment rewarding it. Consider the classic of a high-performing specialist promoted into leadership, not because they’re ready, but because there’s a gap to fill. They’re sharp, driven, and reliable, until they have to manage people. The technical depth that made them indispensable now becomes a trap. They micromanage and can’t delegate. The team underperforms, but the organization sees only surface indicators of deadlines met and work delivered. So they keep rising until something breaks.

This is the Peter Principle in action; people being promoted to the point of their incompetence. Rather than incompetence in the traditional sense, it’s a contextual mismatch. The assumption is that past success at one level predicts success at the next. It often doesn’t.

And when the system lacks a robust progression architecture — clear expectations, calibrated assessments, honest feedback — these mismatches become common.

There’s also the Law of Crappy People. For any given level in a large organization, the least capable person holding that title becomes the de facto standard of what’s accepted. Once they’re in, others benchmark against them. Over time, standards shift downward.

Organizations aren’t negligent, but they’re often unprepared to help leaders navigate the complexity that comes with transition. In high-growth or politically charged environments, the urgency to fill roles outweighs the patience to develop them. Leaders get slotted into stretch roles with little onboarding and even less structural support.

Then layer in culture clash during M&A, restructures, or rapid scaling. Those thriving in one context flounder in another. Not because they became incompetent but because their implicit assumptions — about autonomy, pace, feedback — no longer match the system. These collisions manifest as attrition, conflict, and passive resistance.

Add one more layer: title inflation. In many places, they are used for morale and retention. In others, they’re tightly guarded. But in either case, titles mask capability gaps, making it harder to distinguish role complexity from role competence. A “Director” in one org may be equivalent to a “Manager” elsewhere. But expectations are rarely reset when people move between systems.

All of this means that derailment isn’t just about the individual but also about the organization’s architecture: how it promotes, transitions, defines readiness, and absorbs lack of fit.

When that structure is weak — informal promotions, broken feedback loops, or style over substance — even well-intentioned leaders go off course.

Predicting Derailment

Derailment hides in plain sight. By the time a leader is visibly failing, the patterns have been in motion for months or years. But because derailment at the senior level rarely resembles dysfunction — and often looks like intensity, decisiveness, and commitment — it tends to be rationalized or ignored.

Detection is difficult due to the asymmetrical experience:

- To the leader, it still feels like doing the job well.

- To the leader’s boss, it reads as urgency.

- But to the team, the leader’s volatility is exhausting.

Most systems don’t reward speaking up — especially if the leader is delivering results — so warning signs surface only when unavoidable.

But the signs are always there. They show up first in relationships, not performance metrics. The atmosphere changes. Conversations become transactional and people stop challenging ideas. Humor disappears and high-performers exit quietly. What’s left is execution without engagement; a brittle control that feigns alignment until pressure hits.

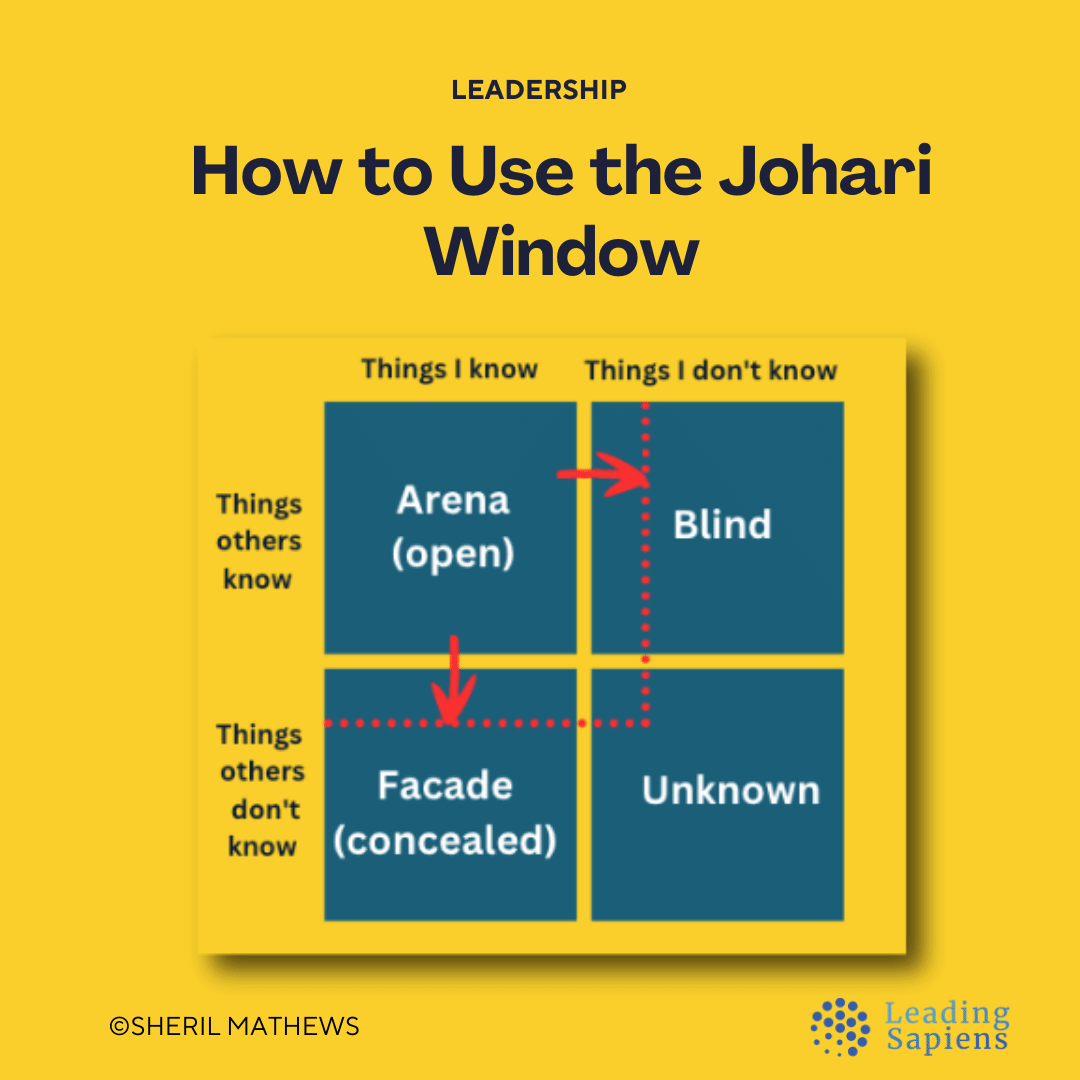

Research backs this up. Gentry et al. [7] found that co-worker ratings of self-awareness — not manager ratings, or self-assessments — best predict derailment and even likelihood of being fired years later. To make matters worse, the higher the leader rises, the wider that self-awareness gap becomes.

Psychologists like Hogan and Courtis have offered taxonomies for these breakdowns:

- Errors of commission: doing what shouldn’t be done; overreaching, reacting impulsively, pushing too hard.

- Errors of omission: what’s not said, not addressed, not confronted. Often invisible, but corrosive.

- Errors of timing: good decisions delivered too early or too late.

- Credibility errors: doing the right thing, but in a way that irritates or alienates. The delivery undermines the impact.

- Qualitative errors: choice wasn’t wrong, but lacked judgment and depth.

Finkelstein added another lens: signs like unnecessary complexity, excessive hype, distraction from fundamentals, and a growing distance from reality. These aren’t traits but patterns noticed by close observers but dismissed by those higher up.

Many organizations treat derailment as a sudden crack in the system. But it can be detected early if people are paying attention. The problem is that most leaders and systems aren’t.

Avoiding Derailment

Leaders who avoid or recover from derailment stay calibrated to their context, others, and themselves. When things go off-course, they don’t double down. They pause, realign, and recalibrate.

That’s harder than it sounds, especially at senior levels where autonomy is high and feedback is diluted. Recovery is hindered by the leader’s inability to metabolize feedback without defensiveness.

Some strategies

Research consistently shows that the most reliable buffers against derailment are not traits but practices: practices around reflection, relationships, and responsiveness.

Here are a few I’ve seen work well:

Self-awareness grounded in feedback. Especially the kind that shows up in unfiltered peer comments and uncomfortable moments. Tools like the Hogan Development Survey can show how others experience you under pressure.

Willingness to change course. Derailment doesn’t happen because of one bad call. Leaders derail because they kept making them long after the context shifted. The turning point comes when the pain of continuing outweighs the fear of change.

Support systems that speak truth. This could be a direct report who won’t sugarcoat, a peer who knows the pattern, or a coach who holds up a mirror. Without these, it’s easy to drift into echo chambers of what worked.

Structured reflection under pressure. Kets de Vries recommends asking:

- What defenses am I relying on that no longer serve me?

- How am I experiencing and expressing emotion, and is it appropriate for my context?

- How honest is my self-perception?

Those who can sit with those questions and act on what they find are most likely to course-correct in time. I’ve added more reflection questions in the last section.

At the organizational level

Recovery and prevention shouldn’t rely on individual heroics. Many derailments are preventable with better org architecture:

Disciplined promotion processes. Define expectations clearly, ensure cross-functional calibration, and treat promotions as design decisions, not rewards.

Advancement tied to developmental readiness, not just performance. Don’t confuse title inflation with readiness. This means evaluating not only what someone has done, but whether they’ve shown the capacity to evolve.

Support during transitions. The most common point of derailment is the jump to a more complex role. This is where systems typically underinvest. Yet it’s where scaffolding like coaching, onboarding, and reset conversations are most needed.

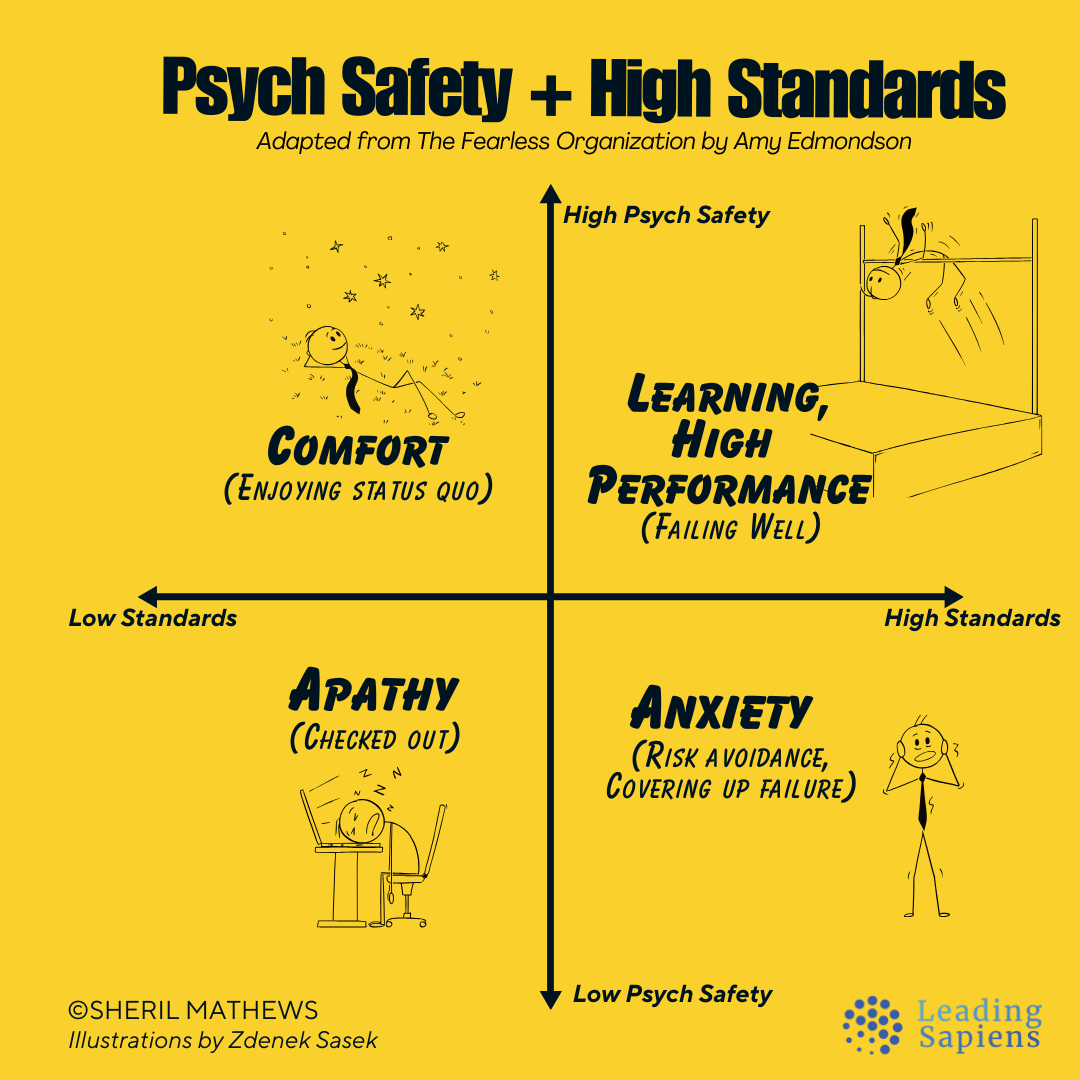

Learning cultures that surface reality. Environments that anticipate errors, normalize feedback, and create space for sensemaking reduce derailment risk. The goal isn’t to avoid failure but to make it easier to detect and recover quickly.

Avoiding derailment isn’t about becoming flawless, but being more reflective, responsive, and context-sensitive.

Reflection questions

The qualities that built your reputation can, under the wrong conditions, quietly erode your effectiveness. The higher you rise, the more room those tendencies have to run. The question isn’t if you have derailers. You do.

It helps to stay alert by regularly reflecting:

- Which of your strengths could become a liability if overused?

- Who will clearly and honestly tell you when that happens? Can you clearly process that feedback?

- What’s worked well in the past but may not fit your current role?

- Who tells you the truth when you’re moving too fast, leaning too hard, or missing something?

- Where are you getting compliance, but not real engagement?

- What would your team say if they could speak freely about how you operate under pressure?

- What signs of wear are showing in your team, decisions, or yourself?

- When did you last change your leadership approach?

Related Reading

References

- Bentz, V. J. (1985). A view from the top: A thirty-year perspective of research devoted to the discovery, description, and prediction of executive behavior.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). The Psychology of Personnel Selection.

- Courtis, J. (1986). Managed by Mistake.

- de Haan, E., & Kasozi, A. (2014). The Leadership Shadow.

- Dotlich, D. L., & Cairo, P. C. (2003). Why CEOs Fail

- Finkelstein, S. (2004). Why Smart Executives Fail.

- Gentry, W. A., et al. (2007). The relationship between self-awareness and leadership derailment across time.

- Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2001). Assessing leadership: A view from the dark side.

- Hogan, R., Hogan, J., & Kaiser, R. B. (2010). Management derailment.

- Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2006). The Leader on the Couch.

- McCall, M. W., & Lombardo, M. M. (1983). Off the Track: Why and How Successful Executives Get Derailed.