It should be considered that there is nothing more difficult to handle, more doubtful of success, or more dangerous to carry through than to initiate a new order of things. For the innovator makes enemies of all those who prosper by the old order while only lukewarm support is forthcoming from those who would prosper under the new.

Their support is lukewarm partly from fear of their adversaries, who have existing laws on their side, and partly because men are generally incredulous, never really trusting new things unless they have tested them by experience. In consequence, whenever those who oppose the change can do so, they attack vigorously...

—Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince

Machiavelli’s dictum is as true today as it was in 1532, perhaps even more so. Except, instead of warring princes and kingdoms, we now have mini fiefdoms inside large organizations.

In a previous piece, I highlighted how high amounts of “frustration tolerance” are key to succeed and thrive in large organizations. This begs the question: why are they so mind-numbingly frustrating to begin with?

One primary reason is that many "leaders" in these orgs aren't leading anyone, anywhere. They're managing the status quo, rubber-stamping decisions, or hung up on slide template changes. Meanwhile, high-performers get disenchanted watching VPs of strategy who never make a strategic choice or directors of innovation who haven't championed a new idea in years.

They have titles but lack what actually matters: the ability to "make happen what wouldn't have happened otherwise"— aka leadership. These are powerful people acting powerlessly.

This creates familiar organizational absurdities:

- You proactively start a cross-functional OKR but two powerful stakeholders have contradictory goals. Rather than force a choice, you water the objective down to "improve cross-team collaboration," which keeps the peace but changes nothing.

- You initiate a voluntary working group across design, ops, and engineering to fix a recurring failure point. Momentum builds which prompts a director to file a complaint that you're "creating a shadow org." Your performance feedback states: "stay in swim lane."

Why is this common? How do you keep a straight head in this madness and still contribute?

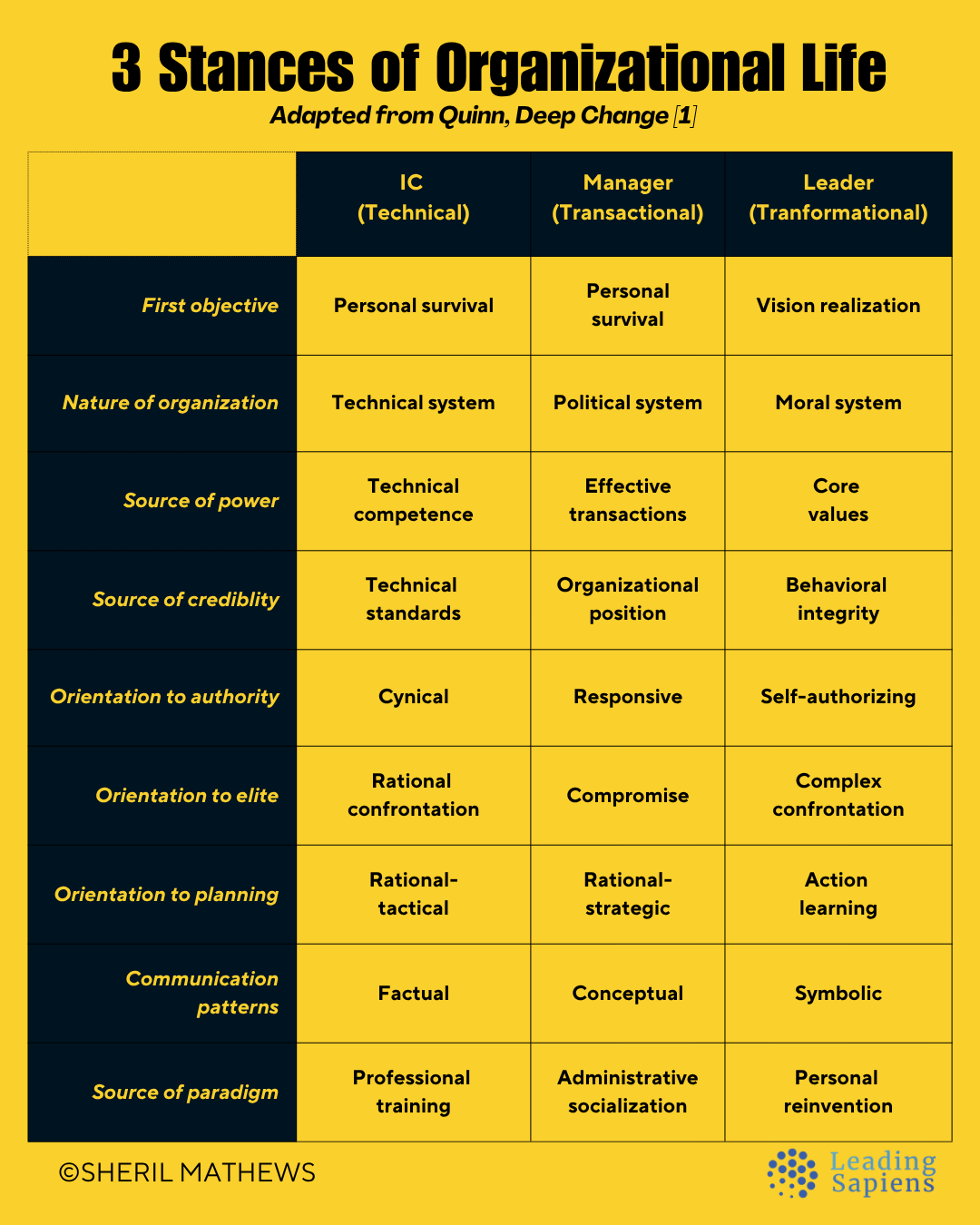

One framework I’ve found useful comes from the work of Robert Quinn at University of Michigan. Most professionals — regardless of title — operate from one of three dominant paradigms: Individual Contributor (IC), Manager, or Leader. Each has a different internal logic.

Once you understand Quinn’s framework, absurdities and stupidity won’t disappear but they stop being personal. They become patterns we can anticipate and account for. In other words, you have an increased capacity for action. Without it, we keep blaming these frustrations on politics, bad luck, or our own shortcomings.

Also note that whether we recognize it or not, we’re always making a choice to operate by a certain paradigm. Burnout often happens when there’s a mismatch between how you think things “should” be vs how they simply “are”.Organizations reward the IC and Manager paradigms, while the Leader paradigm is dangerous territory. No wonder leadership is rare.

Three ways of seeing the world

Quinn identifies three distinct mindsets that professionals embody as they progress. Understanding them shows why talented people plateau, and why organizations desperately need leaders.

Studying this table alone is well worth your time:

The following differences are worth noting:

Individual Contributor (technical)

- Internal Logic: "If I excel at the work, I’ll be recognized."

- Driver: Mastery

- Organizational lens: Technical system

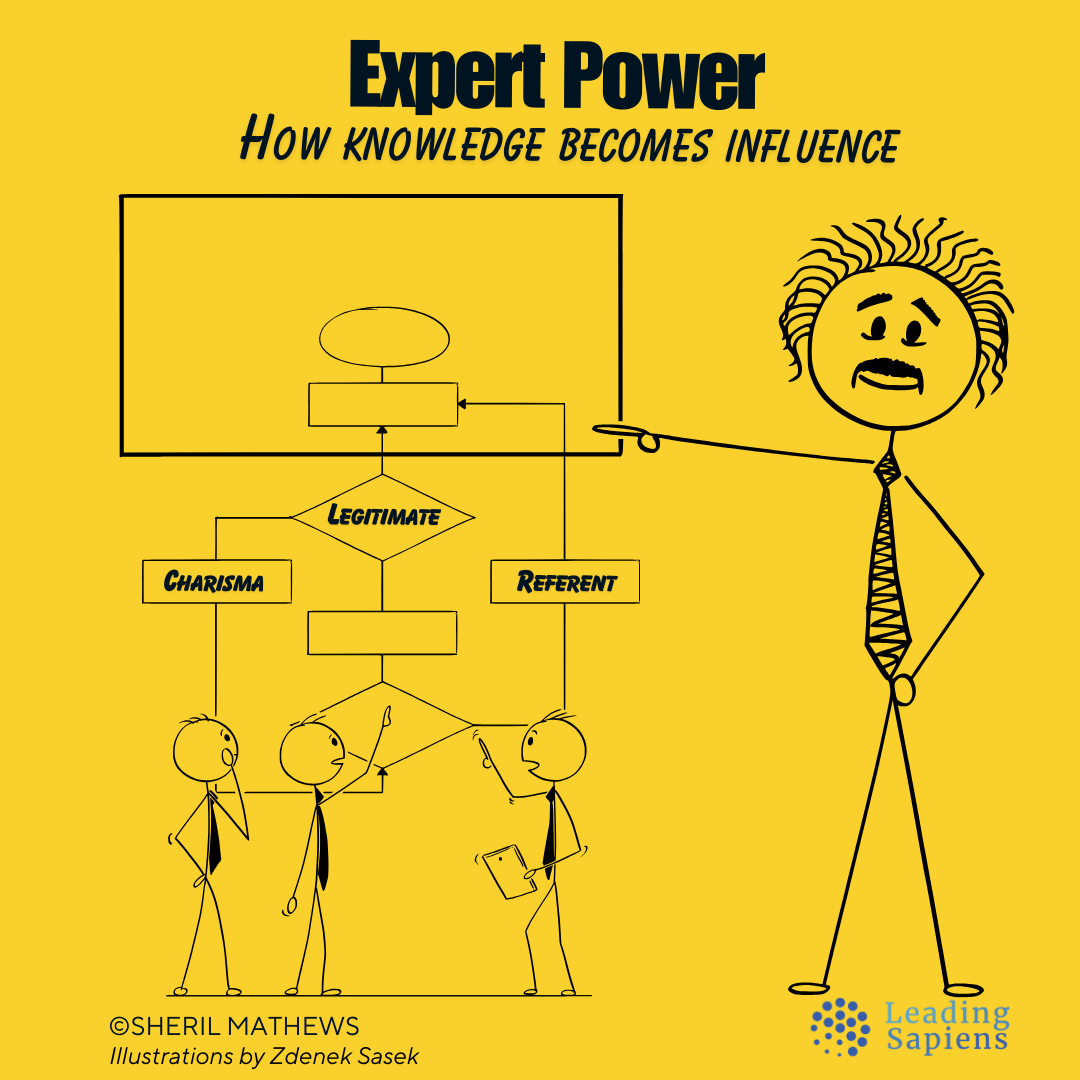

- Basis of power: Competence

Manager (transactional)

- Internal Logic: "If I manage relationships and deliver outcomes, I’ll advance."

- Driver: Stability

- Organizational lens: Political system

- Basis of power: Position

Leader (transformational)

- Internal Logic: "If I live the vision, others will follow, even if I'm rejected."

- Driver: Purpose

- Organizational lens: Moral system

- Basis of power: Behavioral integrity

Each logic is internally consistent and works. But only up to a point. All have predictable failure modes:

- The IC logic breaks down when systems become more about relationships than rationality.

- The Manager logic breaks down when systems require courage, not maintenance.

- The Leader logic is often rejected by the very systems it seeks to rebuild.

All three are necessary though. Organizations need craft (IC), coordination (Manager), and courage (Leader). The problem isn't that any single approach is wrong; it's that many of us don’t recognize what’s actually needed for what we’re trying to achieve.

The IC keeps perfecting technical skills when they need to build influence. The manager optimizes processes when the situation requires transformation. The leader challenges systems that aren't ready to change.

The real tragedy is that people with leadership potential waste years operating by the wrong criteria. To understand how this happens — and more importantly, how to prevent it — let’s take a closer look at each of them

The Individual Contributor (Technical Stance)

Consider Sarah, a data scientist. She's the go-to person for complex analytics, works nights and weekends to perfect her code, and consistently delivers insights that drive business decisions. She represents the best of the IC mindset: deep expertise, technical mastery, and measurable results. While managers spend their days in meetings, Sarah takes pride in shipping “real work”.

Her early career sails on autopilot. But somewhere in the 8-15 year range, Sarah hits a wall. She watches less technically skilled peers get promoted while she's passed over repeatedly.

Walk through any Fortune 500 company and you’ll find Sarahs — brilliant individual contributors whose careers mysteriously stall despite exceptional performance.

The problem runs deeper than office politics. It’s a mismatch of paradigms:

- Sarah believes competence equals authority and defines success through what she personally produces, not what she enables others to achieve or her ability to influence outcomes.

- She dismisses organizational politics as beneath her, not realizing that relationships aren't office drama but essential tools to make things happen in a social system.

- Sarah assumes her work speaks for itself. She waits for recognition instead of working on her positioning — what I call organizational savvy.

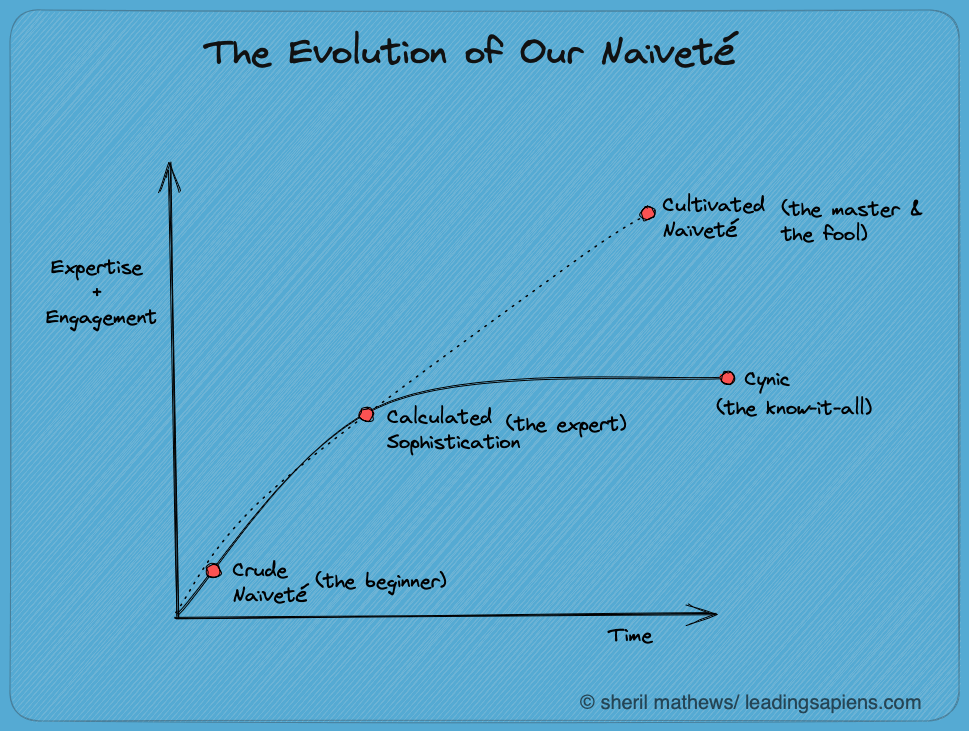

She ends up being the 20-year expert who gets passed over for strategic roles, bitter about "politics" while less experienced colleagues shape the organization's future. She has deep expertise but shrinking influence — a master craftsman stuck in a system that has needs beyond craft.

The IC trap isn't inevitable, but breaking through it requires a painful adjustment: viewing excellence not as solitary craft unto itself, but as a lever for broader impact.

The Manager (Transactional Stance)

Now consider David, a senior analyst recently promoted to team lead. Unlike Sarah, David figured out early that success is not only about individual performance but also getting things done through others.

David sees the world differently. Unlike ICs who believe in the supremacy of personal output and technical solutions, he knows that getting things done requires relationships, positioning, and political acumen. He builds alliances, maintains credibility with senior leadership, and ensures the team delivers.

Initially, this increases his impact far more than he ever had as an IC. He's playing the game, and winning.

But over time, the skills that made David effective start working against him. He becomes so good at navigating the system that he becomes trapped by it. Several years into his role, David finds himself prioritizing what's politically expedient over what's strategically sound. He knows the right answer, but he chooses the safe one because it won't ruffle feathers.

The managerial trap creeps up over time:

- Compromise becomes religion. Skilled at finding middle ground he loses touch with what matters. Every decision seeks the path of least resistance.

- Playing not to lose, he optimizes for avoiding failure rather than achieving breakthroughs. "Don't rock the boat" becomes the doctrine.

- Perpetual fire-fighting means David lives in a reactive mode, managing crises and keeping stakeholders happy, but never stepping back to question why these fires keep happening.

David becomes what one exec calls a "highly paid administrator" orchestrating processes that no longer serve anyone, including himself. He has the title but feels empty, going through motions he no longer believes in.

Most managers plateau in this way. They’ve become too embedded in the system to challenge it. By getting rewarded for playing by the rules and maintaining stability, they hesitate to drive real change. While they may advance in title and responsibility, they remain stuck in transactional thinking.

The transactional paradigm arises from administrative socialization. An organization informally teaches its members this paradigm.

— Robert Quinn [1]

They’ve mastered what I call organizational savvy, but lost something more important: the courage to challenge the systems they’ve learned to navigate well.

The Leader (Transformational Stance)

Maria, a senior manager, operates differently. While Sarah perfects her technical work and David navigates organizational politics, Maria is asking different questions entirely: "What if we're solving the wrong problem? Why do we accept these constraints? What if we change the rules?"

Folks like Maria operate on an entirely different playing field. Where ICs focus on excelling within systems and managers focus on optimizing across them, leaders focus on transforming the systems themselves.

It’s a fundamentally different orientation. Their compass isn't efficiency but direction. The criteria isn't approval from above, but alignment with something worth building, even if it comes at personal cost. This requires departing from conventional organizational and career logic.

For Maria, power isn't granted through position or political maneuvering, but claimed through congruence. Her credibility comes from behavioral integrity: what she says, does, and believes are in alignment. Unlike managers who see power as something that comes from position and political transactions, Maria understands that real power flows from clarity and conviction.

Three things set her apart:

- She's self-authorizing. Maria acts without waiting for permission from the system. She doesn't ask if she can challenge the budget process, she proposes a better way and starts implementing it.

- She's willing to disrupt. While David avoids rocking the boat, Maria actively challenges norms, questions assumptions, and takes unpopular positions when they serve a higher purpose.

- She mobilizes others. Maria doesn't just have teams and direct reports; she creates other leaders. People don't just comply with her directives; they get energized by her and start acting on their own initiative.

But the leader’s transformational stance comes with significant challenges of isolation, resistance, and high personal risk. Ron Heifetz puts it bluntly: leadership is a dangerous job.

Why real leadership is rare

Organizations are natural incubators of the first two paradigms. Our educational systems and our career experiences in organizations naturally socialize us to the technical and transactional paradigms. The strategies of these paradigms are reinforced in nearly all our interactions.

— Robert Quinn [1]

As Quinn notes, the first two paradigms come automatically, but only a select few successfully make the leap to genuine leadership. It’s because going from IC or Manager to Leader is about identity and risk tolerance, not just skills.

Rather than a promotion or permission, it's a decision to stop deferring, stop avoiding discomfort, and stop letting the system define you. And it’s especially difficult because the very systems that promote people into positions of authority also discourage actual leadership.

Systems reward stability, not disruption

The uncomfortable truth is that most organizations don’t actually want leaders like Maria.

They say they do, but reality is a different story. The same company that claims it wants “innovation” and “disruptive thinking” also has 13 approval layers for a $10K software purchase. The system says it wants change while punishing those who attempt it. Why?

- Companies are risk-averse by default; disruptive leaders introduce uncertainty that makes senior managers and executives nervous.

- As Machiavelli noted, change threatens existing power structures; transformational leaders redistribute power away from those who spent years accumulating it.

- Stability is comfortable; even managers who push “innovation” prefer predictable routines to the chaos of reinvention.

Thus organizations unconsciously suppress transformational leadership by rewarding rule-followers and sidelining challengers. It’s baked into the structure.

Unlike the transition from IC to Manager—which comes with clear support in the form of promotions, raises, and expanded scope—the move to genuine leadership is often punished, not rewarded. While David gets credit for maintaining stability and hitting the numbers, Maria gets questioned for “being too intense, “creating unnecessary complexity” and “not being a team player.”

Maria gets misread by others. Colleagues call her naive, arrogant, or difficult because she's not playing by the conventional script. Her direct reports love working for her, but peer managers complain she “makes them look bad”. She’s accused of “moving too fast” and “not considering all stakeholders.”

Her performance review concludes she needs to work on “collaborative leadership.”

Acting without guarantees

David operates within defined processes and predictable outcomes. In contrast, Maria operates in the unknown often without clear markers of success.

This is terrifying because:

- There's no predefined roadmap for challenging the status quo. Unlike the managerial stance based on KPIs and performance reviews, real leadership operates in ambiguity.

- You must be willing to fail publicly. The fear of being seen as wrong, naive, or reckless stops many from doing what it takes.

- Professionals build their identity on being competent and respected. Taking transformational risks means willingly putting that status at stake.

The burden of self-authorization

Managers like David operate within established norms. In contrast, Maria creates new benchmarks and acts before anyone gives her permission.

This isn’t easy. Professionals spend entire careers waiting for approval, recognition, and validation before taking big steps. We're conditioned from childhood to seek external legitimacy.

Self-authorization means becoming the source of your own legitimacy. Maria acts not because she was given permission, but because she believes the action serves something larger than herself.

This perspective, in which a man sees himself only as an individual contrasted with other individuals, and not as a genuine person whose transformation helps towards the transformation of the world, contains a fundamental error. The essential thing is to begin with oneself, and at this moment a man has nothing in the world to care about than this beginning. Any other attitude would distract him from what he is about to begin, weaken his initiative, and thus frustrate the entire bold undertaking.

— Martin Buber [3]

Why bother

If organizations systematically resist change, why develop leadership capabilities at all? I’ll share two reasons to do so.

The first one is simple: resistance creates opportunity.

While organizations may not explicitly reward transformational leadership, they desperately need it. The very dysfunction you observe — meetings about meetings, strategies that go nowhere, or talented people checking out — are symptoms of leadership scarcity. Those who develop true leadership capabilities become invaluable precisely because they're rare. At a time when AI can optimize processes and analyze data better than any human, the premium will be for those who can do what machines can't. But as I noted, this path can be risky.

That brings us to the second reason. Once you’ve achieved a reasonable amount of success by traditional standards of money and titles, the only way you can continue playing the game without losing your soul is by inventing your own terms, and reinventing yourself.

The “how” — different ways you can achieve this — has many variations but the “why” boils down to this simple idea.

Where are you at?

Making shifts requires awareness and honest self-assessment. The following questions can help reveal which paradigm currently drives your actions and where you might be stuck:

- Are you optimizing for validation, coordination, or transformation?

- When did you last act on principle, knowing it might cost you? What was the outcome and what did it teach you?

- What drives your decisions? Is it accuracy, alignment, or integrity?

- In your org who speaks hard truths? Are they being ignored, protected, or punished?

- Where does your authority come from? Is it skills, role, or convictions?

- What rules have you internalized that no longer serve your aims? What do you need to unlearn in order to grow?

- If your title were removed, what would remain?

- Have you mistaken having a title for having influence? Are you shaping the conversation or simply managing logistics?

- Would you rather be dismissed for doing what needed done, or promoted for preserving what's broken? What does your answer say about your actual orientation?

Related reading

Sources

- Deep Change: Discovering the Leader Within by Robert E Quinn.

- The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli

- The Way of Man According to the Teachings of Hasidism by Martin Buber