"I don't want to step on anyone's toes." This is a common and reasonable stance in organizational life. But this mostly logical approach often does more damage than good.

If “that’s not my job” tops the list of career-limiting phrases, an overcautious respect for boundaries is equally limiting. It's particularly damaging if you’re the conscientious type who knows what you’re doing.

Impact often lies in the gray zone between clear authority and clear overreach. Visible constraints like hierarchies, roles, and processes are actually easier to navigate than the invisible ones we create for ourselves.

There's an art to exceeding your authority in ways that build trust, but it feels dangerous. The skill is in thoughtfully testing and expanding the boundaries of our perceived authority.

In today's piece, I explore how to master this critical balance. In my follow-up, I'll share a framework that goes deeper into this nuance.

When silence talks

Imagine you're in a meeting where everyone's skirting around an issue. You understand exactly what's happening, but an internal filter kicks in. You wonder: Am I the right person to bring this up? So you stay silent.

These moments of hesitation are defining twice over: first in our immediate impact, and second, more lastingly, in how others perceive us.

While these moments seem to be about risk, potentially leading to embarrassment or appearing overly ambitious, they're actually about legitimacy and leadership.

You're not worried about being wrong. You're concerned about violating some implicit boundary between contribution and overreach. But where did this boundary come from? Who drew it? And what would happen if you crossed it thoughtfully?

Zones of authority

While boundaries of authority may seem abstract, they exist in clear patterns across organizations.

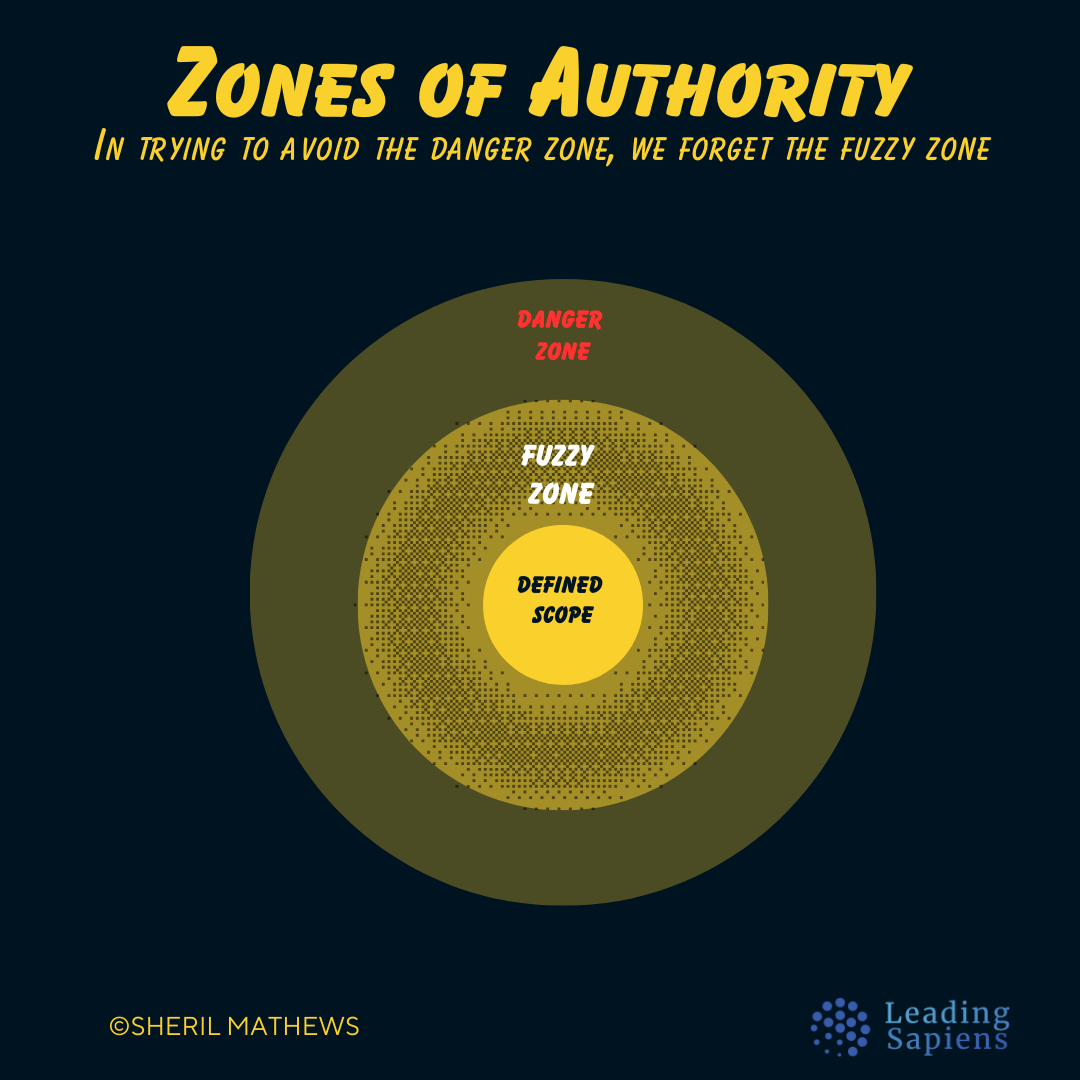

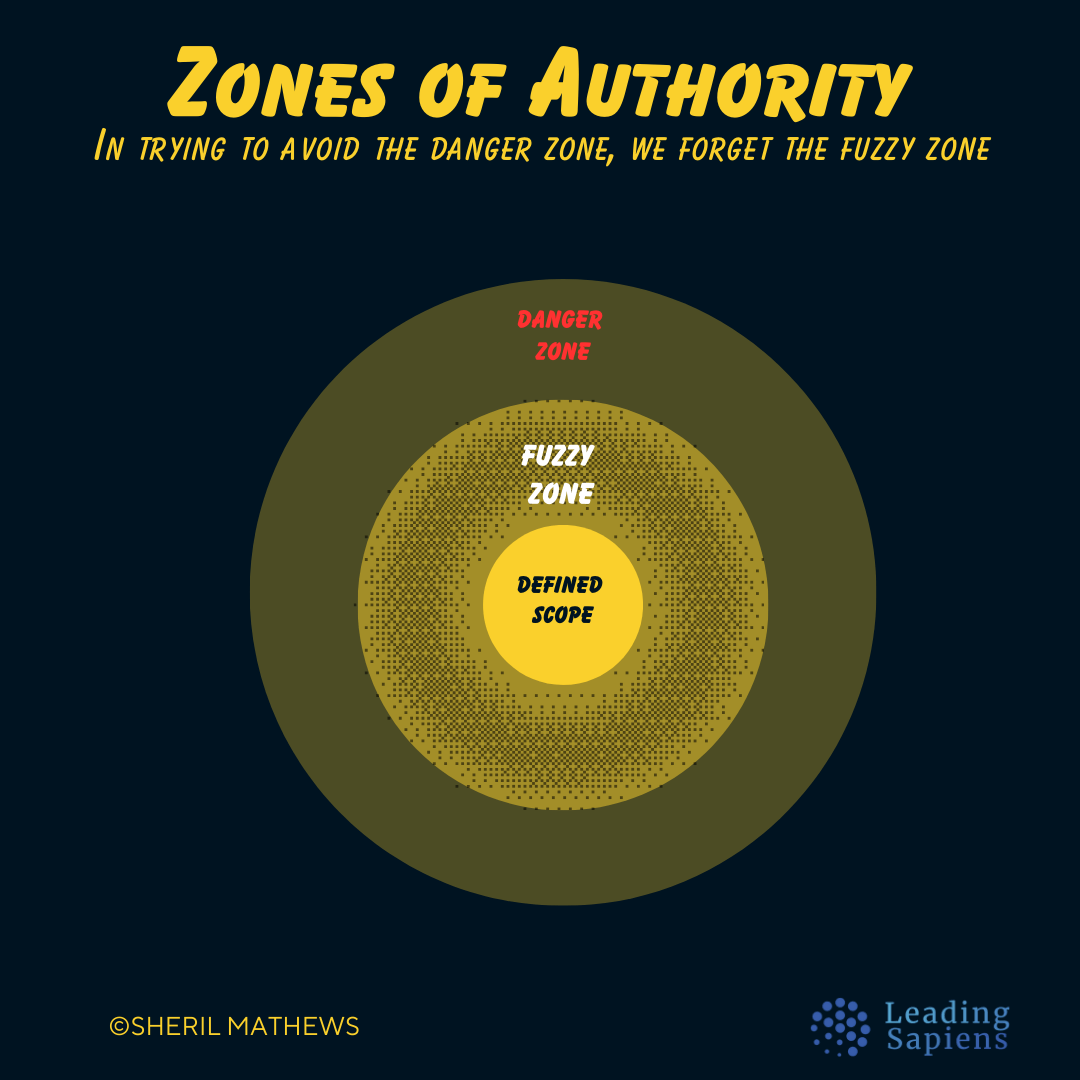

Picture them as three circles: your formal authority in the center, a danger zone of clear overreach at the outer edge, and between them, a rich but fuzzy middle zone of potential impact. [1]

Most conscientious professionals understand their formal authority well and recognize clear danger zones.

But, this binary view misses the critical middle ground where leadership is often required.

It's in the fuzzy zone in between where the greatest opportunities for impact often lie. It's neither clearly within nor outside your authority, but a space where your engagement can add unexpected value. It's how roles naturally evolve, and where future responsibilities are born.

The challenge is learning to navigate this middle zone wisely. In those moments of hesitation — when you wonder if it's your place to speak up — you're likely standing at the edge of this zone.

Leading in the gray zone means testing boundaries and creating possibilities. Recognizing that there is in fact a third fuzzy zone increases freedom both literally and metaphorically.

Obedient contributors

Most high performers build their careers on a strong sense of responsibility. We meet expectations, don’t overstep, and know how to be useful without making ourselves central.

In early career, being a reliable executor is an asset. You build your reputation through consistent delivery, minimal drama, and staying in your lane. You're trusted because you execute without making waves.

But as your role's profile increases, the nature of the work fundamentally shifts. Ambiguity increases, contradictions multiply, and just execution isn't enough. It demands a kind of judgment that requires going beyond the clear boundaries of your position.

You must be comfortable operating at the edges of your formal authority, using influence and discernment instead of pure execution.

The exercise of adaptive leadership is dangerous in part because you always dance on the edge of your scope of authority, at least with respect to some of your authorizers — whether they are your superiors, peers, subordinates, or people outside your organization. You push the limits of what others think you ought to be doing.

— Heifetz, Grashow, Linsky in Practice of Adaptive Leadership

And this is where obedient contributors begin to falter due to over-reliance on inherited instincts:

- wait to be asked

- don’t speak unless it’s your area

- avoid controversial topics unless someone else raises it first

These are leftovers from earlier stages of professional identity. But left unchallenged, they can turn reliability into irrelevance. People trust you to implement, but not for direction. Someone they like, but don’t follow.

Conscious challengers

The move from contributor to challenger isn’t about being louder or bolder. It’s a subtle shift in how you relate to authority, both your own and others’.

Conscious challengers don’t ask for permission. But they also don’t force their way in. They’ve developed an internal sense of legitimacy – the capacity to hold your own perspective as valid, even when it’s not yet recognized by the group.

You learn to shape conversations. The impact is not from volume but orientation. You:

- Ask the unasked question.

- Offer reframing that resets the discussion.

- Avoid rushing to resolution.

You act not from certainty but responsibility. Speaking up not because you’re the smartest person in the room but because waiting for someone else is no longer an option.

This turning point less about rash boldness and more like considered courage. It’s becoming what Robert Quinn calls self-authoring.

You become someone who can state what's required – without permission and without apology.

Rewriting the script

Much of what limits us isn’t formal policy. It’s accumulated social conditioning. It’s the scripts we’ve internalized over years of trying to stay useful, professional, and promotable.

- “Don’t challenge leadership.”

- “Stay in your lane.”

- “Don’t question an already decided matter.”

- “Don’t point out a problem without a solution.”

- “Don’t be the person who makes things awkward.”

These aren’t written down, but enforced everywhere through micro-reactions, career folklore, and social cues. The hard part is these aren't irrational. They’re functional and helped you survive earlier seasons of your career.

But their usefulness declines as your scope increases. What once kept you safe now makes you ineffective. So the work is not to abandon caution but to interrogate the script.

Ask:

- “What has helped me survive early career but now keeps me small?”

- “Who taught me that, and do I still need it?”

- Does it still fit my current role or the one I’m growing into?

- “Where am I still waiting for permission, when the system needs me to show up?”

Until we update the script, we’ll keep limiting ourselves even in situations that are waiting for us to step in.

Making the shift

The transformation doesn't happen through sudden changes but consistent, low-risk experimentation.

You don’t need to confront the senior VP or dismantle groupthink on day one. Just take one step closer to the line than usual:

- Approach risk as curiosity.

- Float a hunch instead of locking it into a fully formed position.

- Make an observation instead of declaring a judgment.

None of these require formal authority.

With repetition, tolerance increases, legitimacy expands and your voice gains weight. Not because you now talk more, but because you speak from a place that’s real.

Your role in the system

As Heifetz noted, going from obedient contributor to conscious challenger is learning to operate effectively at the edges of your role, where formal authority ends but responsibility continues.

With this shift, your role in the system changes. Now you’re not just a contributor, but also a reference point.

- They seek your framing, not because of seniority, but clarity.

- You’re involved in decisions, not because you insist, but because you see what others miss.

- Others take cues from you not because you have positional power, but referent power.

When you stop waiting for permission and start moving from internal legitimacy, you create something valuable: the capacity to see what needs to be done and help others see it as well.

Consider these practical starting points:

- What do I see that others are missing?

- What conversation is needed that no one is initiating?

- Where can I contribute more if I stopped waiting for permission?

- Whose permission am I waiting for?

- What edge of authority am I not exploring?

- Where am I being invited to lead but haven’t yet accepted the role?

This isn't about becoming someone else but bringing more of your insight and capability to the work that matters.

Authority isn't just handed down. It's also earned by consistently engaging with what the work really needs – not just what your role allows.

Sources

- The Practice of Adaptive Leadership by Ron Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, Marty Linsky