Leadership advice often focuses on communication style: how to be clearer, more persuasive, etc. While valuable, these tactics eventually hit a ceiling. You learn techniques but revert to old patterns under pressure, or the improved "delivery" somehow doesn't create the changes you hoped for.

That's because language operates at a more fundamental level than most leadership advice suggests. Like an invisible operating system, it shapes how we think, relate, and act.

The primary factor keeping us stuck isn't a lack of communication techniques; it's that our everyday language works against us. That's the central point Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey make in How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work (2001).

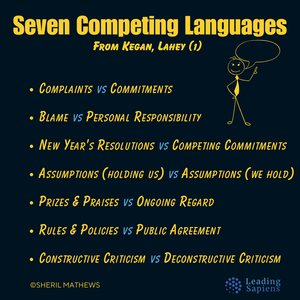

They identify seven “competing languages” — pairs of ways of speaking with two different orientations to the same issue.

- On one side is familiar language that’s effortless: complaint, blame, rules, and quick fixes. It's the language of reflex, safety, and control.

- The other is a more generative language that takes practice: commitment, responsibility, inquiry, and genuine agreements. This is the language of growth and ownership.

Each competing language is a default way of speaking that reflects a habitual way of thinking. They are “competing” because the old ones keep tugging at us even as we strive toward the new.

Effective leadership is less about mastering new techniques and more about becoming fluent in these deeper language shifts. The task is not to eradicate the old languages but to recognize and shift when context demands it. Without these shifts, we remain trapped in what Kegan and Lahey call our immunity to change.

(1) From Complaint to Commitment

We underestimate the sheer amount of workplace conversation that's complaint. Two acronyms summarize this well: NBC (Nagging, Bitching, Complaining) and BMW (Bitching, Moaning, Whining).

We grumble about broken processes, poor communication, and absent accountability. On the surface, complaints are critiques of the outside world, evidence that the problem lies elsewhere.

But every complaint carries a hidden signal: it reveals something you care about deeply enough to feel violated when it's missing.

Beneath the surface torrent of our complaining lies a hidden river of our caring, that which we most prize or to which we are most committed.

Strip away the frustration, and what remains is a commitment:

- "This team is not accountable" also means "I want to work where people honor their word".

- "My boss doesn't listen" reveals "I want relationships built on respect and dialogue".

- "This place is so disorganized" shows that "I am committed to order, clarity, and coherence."

The shift from complaint to commitment relocates action:

- Complaints externalize; they reinforce that someone else needs to change.

- Commitments internalize; they surface what we can own, model, and invite others into.

The language of complaint essentially tells us, and others, what it is we can’t stand. The language of commitment tells us (and possibly others) what it is we stand for. Without having our complaints taken away and without giving them up, this first transforming language enables us to make a shift from experiencing ourselves as primarily disappointed, complaining, wishing, critical people to experiencing ourselves as committed people who hold particular convictions about what is most valuable, most precious, and most deserving of being promoted or defended.

Leaders are swimming in complaints, both their own and others'. If you treat complaint as noise, you miss the underlying values driving them. In contrast, if you treat it as commitment, you unlock energy, clarity, and purpose.

The practice is simple: when you catch yourself complaining, ask "What commitment is this pointing to?" When you hear others complaining, ask "What do they care about so strongly that it shows up as frustration?"

This transforms complaint from resignation into insight, often the first step in overcoming the inertia of the status quo.

(2) From Blame to Personal Responsibility

Blame is the default language of organizational life. When things go wrong, the instinct is to locate the fault elsewhere: "They dropped the ball," "Finance is too slow," "The client is being unreasonable." It feels safe because it keeps the spotlight away from us.

Kegan and Lahey point out that blame protects us from examining our own role in the pattern. The competing language here is personal responsibility — not in the narrow sense of guilt or self-blame, but in the broader sense of acknowledging how we are participants in the very systems we complain about.

We tell stories on ourselves, not for the purpose of humiliating or diminishing ourselves but to begin putting them in a place where we can look at them and learn from them. We tell our stories so we can stop being our stories and become persons who have these stories. We tell these stories so that we can become more responsible for them.

The shift is fundamental:

- Blame focuses outward. It reinforces a narrative of helplessness, as though the environment alone dictates outcomes.

- Responsibility looks inward as well. It asks: What am I doing (or not doing) that allows this pattern to persist?

Consider a leader frustrated with low team engagement. Blaming sounds like: "This team is lazy and entitled." Responsibility sounds different: "What have I done — or not done — that is enabling disengagement? Have I clarified expectations and created the conditions for ownership?"

By reclaiming a piece of the problem, you reclaim a piece of the solution. It moves you from critic to actor. It doesn't deny external factors or others' shortcomings, just refuses to make them the whole focus.

The paradox is that claiming responsibility gives you more freedom. You stop waiting for others to change and begin experimenting with what you can. People trust leaders who own their part in the mess. It signals maturity, humility, and seriousness.

Blame will never fully disappear and will always compete with responsibility. The practice is to notice when it takes the microphone and then deliberately shift: What responsibility can I take here, even for 5% of the outcome? That small adjustment can change the entire conversation.

(3) From New Year’s Resolutions to Competing Commitments

Every January, we make resolutions: "I'll be less reactive," or "I'll delegate better." Leaders make promises to themselves after feedback or a performance review. Yet, like most New Year's resolutions, these promises evaporate under pressure.

Kegan and Lahey argue that this is not due to weak willpower. It’s because every sincere commitment has a competing unconscious commitment powerful enough to derail change.

Take a leader who vows, "I need to give more direct feedback." A few weeks later, nothing has changed. Why? Because beneath the resolution lies a competing commitment: "I'm committed to being seen as kind and supportive." Or "I'm committed to avoiding conflict so people will still like me." You're genuinely committed to both sides — giving direct feedback and maintaining harmony. The two pull against each other, like a tug-of-war inside your leadership identity.

The problem isn't that one commitment is false; it's that both are true. Resolutions fail not because you don't care, but because you care about two things at once, and the hidden one usually wins.

A competing commitment is a hidden contract you've made with yourself, usually to stay safe.

Our… commitments name something of greater consequence than a disposition, trait, or attitude (such as “I don’t like to make others feel threatened”); they name a way in which we may be actively spending ourselves (“I am committed to not making others feel threatened”). They tell us an important thing we are up to—doing—in our lives.

They also remind us we are doing what we are doing on behalf of a powerful, normal, human motive: to protect ourselves. There need be nothing shameful about self-protection; in fact, in the abstract, self-protection is clearly a crucial act of self-respect.

The problem is not that we are self-protective, but that we are often unaware of being so.

The trick is to treat failed resolutions not as moral weakness, but as a diagnostic tool. Each broken promise points to an unspoken loyalty. Once you name that loyalty, you can decide: Is it still serving me? Does it need to be renegotiated?

(4) From Big Assumptions to Testing Assumptions

If competing commitments are the hidden structures that shape our behavior, big assumptions are the bedrock they're built on. These are deep, taken-for-granted beliefs about how the world works, so ingrained that we mistake them for facts.

What is a Big Assumption? In our language, an assumption is “big” if we do not actually take it as an assumption but instead as the truth... Assumptions-taken-as-truth are what we mean by Big Assumptions. They are not so much the assumptions we have as they are the assumptions that have us.

One leader may hold the assumption: "If I don't have all the answers, people will lose confidence in me." Another might assume: "Conflict always damages relationships." Or: "Delegating will make me less valuable."

Big assumptions are powerful because they feel like reality and are rarely questioned. They silently organize our choices, emotions, and what we notice in the environment.

The problem isn’t that assumptions exist — they always will — but that they remain unexamined. Left untouched, they keep us locked in old patterns. The competing language here is testing assumptions.

Testing assumptions means treating them as hypotheses, not truths. This shift, from fact to hypothesis, opens new paths. Instead of saying, "If I speak up, my boss will think I'm undermining her," you ask: "What small, safe experiment could I run to see if that's true?" Maybe you voice a dissenting view in a low-stakes meeting and observe how it lands.

Testing doesn't mean discarding assumptions recklessly. It means running thoughtful, low-risk experiments that generate real evidence. With enough experiments, you discover that many "truths" are exaggerated, outdated, or only true in certain contexts.

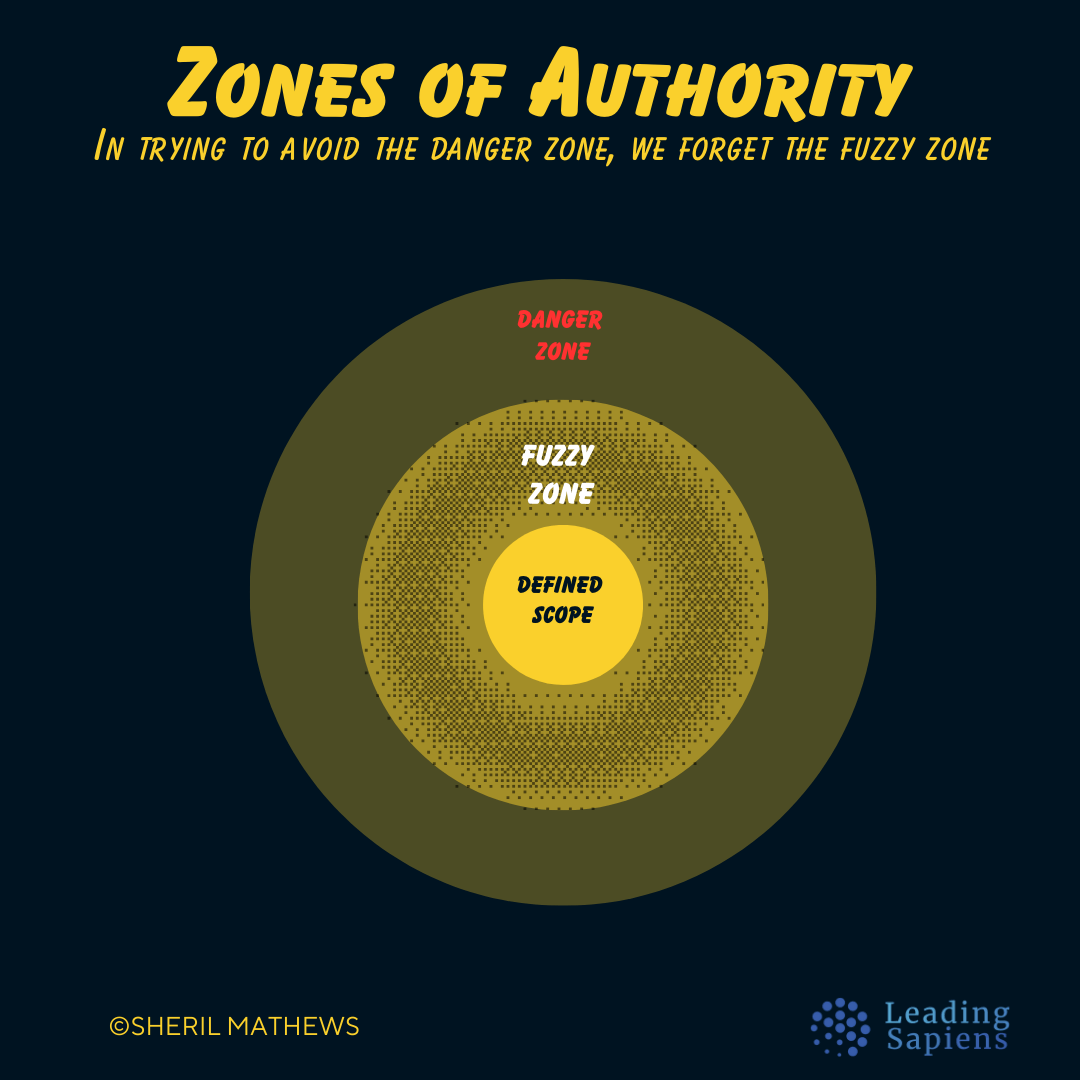

I explored this aspect from a different angle in a previous piece: Please Exceed Your Authority.

A round of modest tests might be followed by tests of a slightly bigger kind. As we come to trust there is firm ground beyond the imagined limits of our Big Assumptions, we shift our weight and move out onto new spaces. By such small steps, we emerge from the bedrooms of our established habits of mind.

This shift reclaims freedom. You no longer have to live as a prisoner of unexamined beliefs. There's a humility in this stance that says: "I could be wrong. I will find out by trying." That humility, paradoxically, builds credibility. Teams trust leaders who are willing to test their assumptions publicly.

(5) From Prizes and Praises to Ongoing Regard

An accepted truism in modern organizations is that motivation requires recognition. Leaders rely on praise, awards, or public shout-outs as the currency of encouragement. And it works, at least on the surface. Kegan and Lahey call this a “language of prizes and praises”: a way of reinforcing behavior that still positions the leader as the judge and the other as the performer.

It creates a subtle asymmetry: I hand out approval; you earn it.

Recognition isn’t wrong but it’s intermittent and conditional. It creates a cycle where people perform for the prize rather than develop for themselves. At its worst, it traps individuals in external validation loops, where the absence of praise feels like failure.

The alternative is the “language of ongoing regard.” Instead of trophies or applause, it’s about steady, specific acknowledgment of someone’s presence, effort, and contribution.

We call the regular expression of genuinely experiencing the value of a coworker’s behavior the language of ongoing regard. Ongoing regard has two faces, one of appreciation and the other of admiration. Consider how these two powerful positive feelings have somewhat different qualities and rhythms... We imaginatively inhabit the other’s world and find ourselves instructed, inspired, or in some way enhanced by the other’s actions or choices.

Notice the difference. Ongoing regard is:

- Descriptive, not evaluative. It names what happened and why it mattered, rather than passing judgment.

- Continuous, not episodic. It happens in the flow of work, not just at highlight moments.

- Mutual, not hierarchical. Anyone can offer it, not just the leader.

The Value of Being Valued

We all do better at work if we regularly have the experience that what we do matters, that it is valuable, and that our presence makes a difference to others. We may know in our hearts that what we do matters, but it is certainly confirming to hear the words from others. We do not, after all, work and live in a vacuum. Believing that what we do and how we do it makes a difference can also lead us to take additional care in performing our work.

Perhaps more important, hearing that our work is valued by others can confirm for us that we matter as a person. It connects us to other people. This is no small matter in organizations where the pace and intensity of work can lead a person to feel isolated.

This sense that we signify may be one of our deepest hungers. One way we experience that what we are doing at work is valuable is by hearing regularly from others how they value what we do.

This shift changes the fuel teams run on. Instead of dangling carrots, it’s a climate of recognition woven into daily interactions. People feel seen, not scored. And over time, this builds intrinsic motivation and stronger trust that prizes can never buy.

(6) From Rules to Public Agreement

Organizations run on rules: formal policies, handbooks, and unspoken norms that define what people can and cannot do. They provide clarity, set boundaries, and reduce ambiguity.

But rules are also blunt instruments. They’re imposed from above, often without much conversation, and can quickly become disconnected from the realities on the ground.

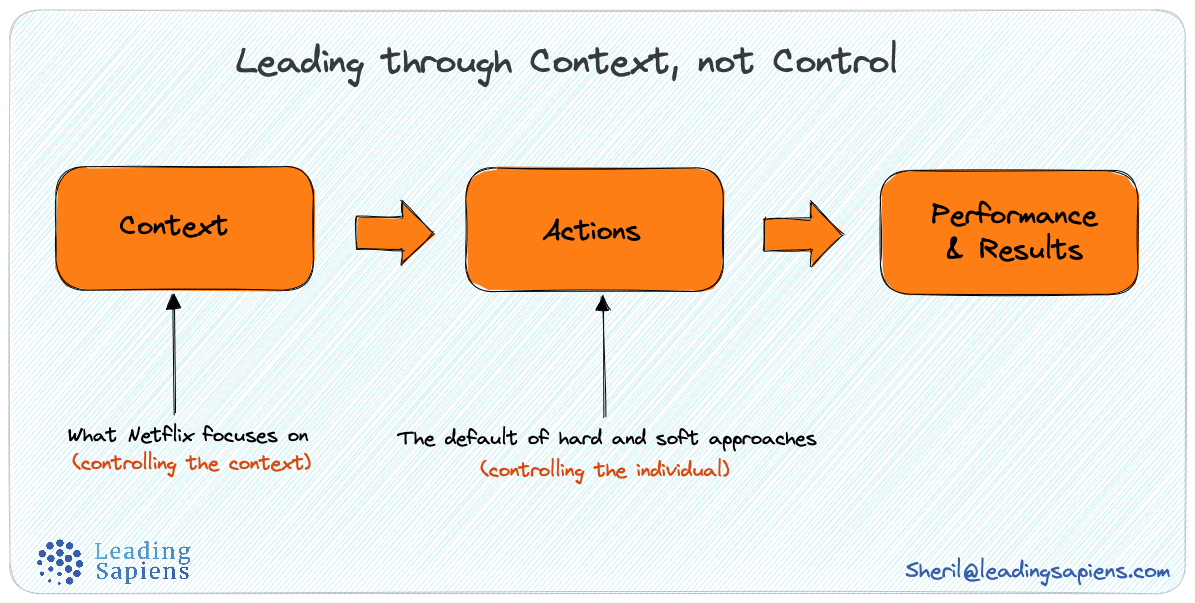

Rules don’t generate commitment; they generate compliance. And compliance, while tidy on paper, is brittle in practice. When circumstances shift, or when no one is watching, it tends to break down. This is why Netflix operates on the principle of context, instead of rules.

The alternative language is public agreement. Instead of rules as external dictates, teams openly negotiate and articulate what they expect of each other. Agreements are explicit, co-created, and visible. They reflect shared ownership rather than top-down enforcement.

Consider the difference:

- A rule says, “You must submit your report by Friday.”

- A public agreement sounds like, “We’ve agreed as a team that Friday deadlines allow us to keep projects moving. Can we count on each other for that?”

The second doesn’t dilute accountability but deepens it. When people help shape the agreement, they’re more likely to feel responsible for upholding it. And when circumstances change, it can be revisited, rather than quietly broken.

The two principal outcomes of a language of public agreement are (1) the experience of organizational integrity (in contrast to ordinary experiences of organizational unfairness, inattentiveness, or ineffectiveness, which create the demoralizing and enervating experience of disintegrity); and (2) the use of violations as a resource for surfacing further inner contradictions for our learning (in contrast to treating violations as the professional equivalent of shameful sin).

In leadership, this is pivotal. It means creating conditions where agreements can be surfaced, questioned, and renewed, rather than assuming that compliance will hold indefinitely. The work isn’t about designing ever-better rules; it’s cultivating a shared language of commitment and flexibility.

(7) From Constructive Criticism to Deconstructive Criticism

“Constructive” criticism has become part of our vernacular to the point we don’t question it. The idea is to frame feedback in a palatable way, wrap the negative in positives, and present it as advice for improvement. At best, it makes hard truths easier to hear. At worst, it’s a polite mask for avoidance, more about preserving harmony than addressingwhat needs to be said.

This language of constructive criticism has built-in limits. It assumes one person holds the truth and the other needs correction. That dynamic reinforces hierarchy and shuts down curiosity.

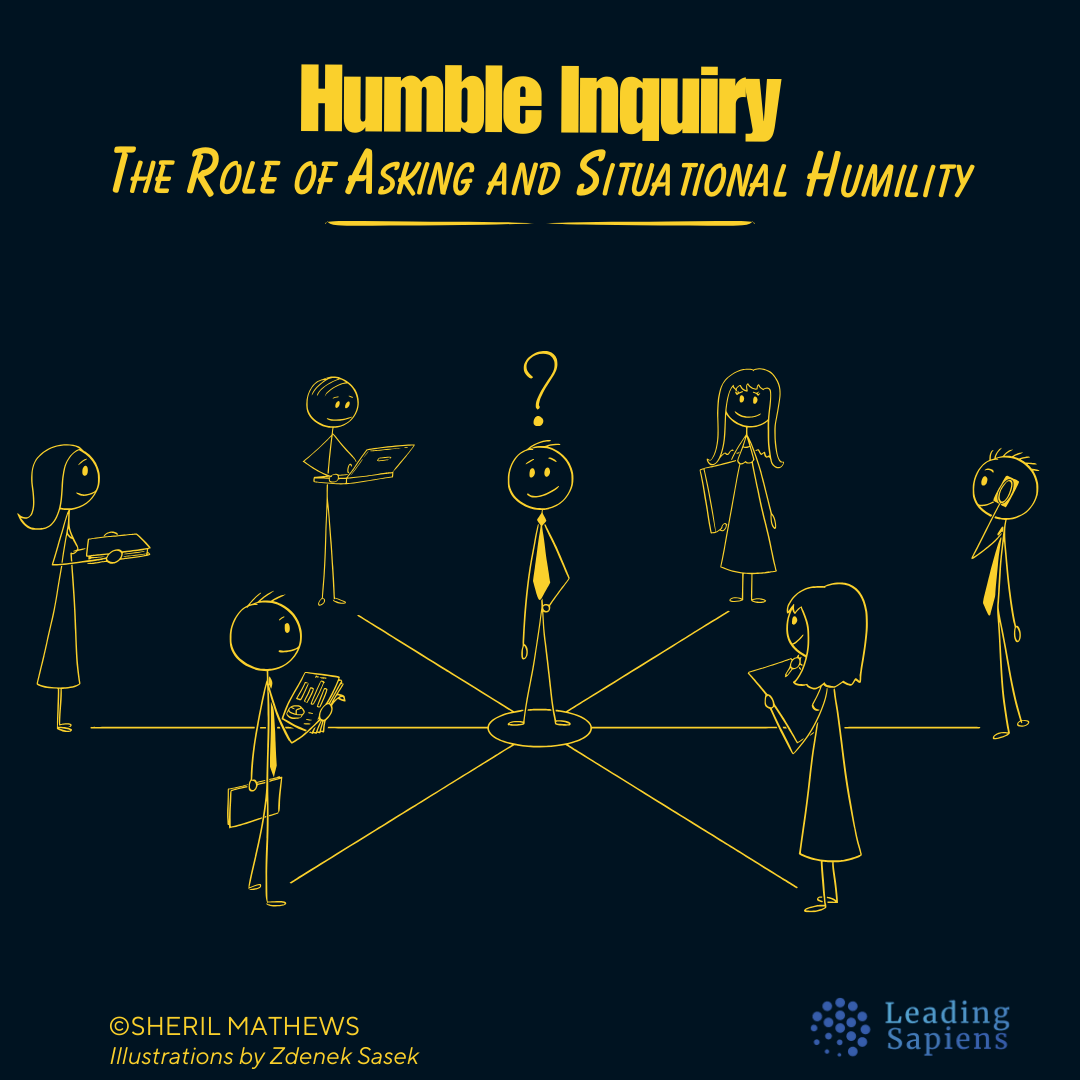

The alternative is deconstructive criticism. Instead of one person offering a polished critique, both parties engage in a conversation that unpacks the assumptions, interpretations, and blind spots in a situation. The goal isn’t to fix someone but to expand the shared understanding.

For example:

- Constructive criticism says, “You need to manage your time better on this project.”

- Deconstructive criticism sounds like, “When the project ran late, I understood it as a time-management issue. But are there other factors I’m missing? How do you see it?”

... behind the apparent virtue of constructive criticism there lies a collection of barriers to learning that can be overcome by stepping back not from our negative evaluations but from a truth-claiming relationship to our negative judgments.

We call this stance a deconstructive one because its central intention is neither to tear down nor build up but instead disassemble, and the object of attention is not first of all the other but our own evaluation or judgment.

This shift requires humility to recognize that your critique may be partial or distorted. It also requires a kind of psychological, more existential, courage to make your own interpretations available for scrutiny. What emerges is not just feedback but a co-created learning process for both parties.

It turns feedback from a one-way street into a shared inquiry. In this way, criticism doesn’t end the conversation but opens it.

Leaders are language leaders

The seven competing languages are a developmental arc that effective leaders must navigate: first mastering the inner moves of personal transformation (first four), then extending those capabilities into the relational realm (last three) where culture is shaped.

Language doesn't just describe reality—it constructs it. And this brings us to the most important point:

This premise that work settings are language communities brings us to a corollary premise: all leaders are leading language communities. Though every person, in any setting, has some opportunity to influence the nature of the language, leaders have exponentially greater access and opportunity to shape, alter, or ratify the existing language rules.

In our view, leaders have no choice in this matter of being language leaders; it just goes with the territory. We have a choice whether to be thoughtful and intentional about this aspect of our leadership, or whether to unmindfully ratify the existing drift of our community's favored forms. We have a choice to make much of the opportunity, or little. We have the choice to be responsible or not for the meaning of our leadership as it affects our language community.

But we have no choice about whether we are or are not language leaders. The only question is what kind of language leaders we will be.

Organizations are flooded with people fluent in complaint, blame, and broken resolutions — languages that are natural but trap teams in loops of frustration.

As Kegan and Lahey note, leaders have the most leverage to meaningfully shift these patterns. The seven competing languages are an essential toolkit for being an intentional language leader.

Related Reading

Sources and references

- Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Laskow Lahey. How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work. 2001.

- Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Laskow Lahey. Immunity to Change. 2009.

- Argyris, Chris, and Donald Schön. Organizational Learning. 1978.

- Argyris, Chris. Overcoming Organizational Defenses. 1990.

- Kegan, Robert. The Evolving Self. 1982.

- Kegan, Robert. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. 1994.

- Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Laskow Lahey. An Everyone Culture. 2016.

- Berger, Jennifer Garvey. Changing on the Job: Developing Leaders for a Complex World. 2025.