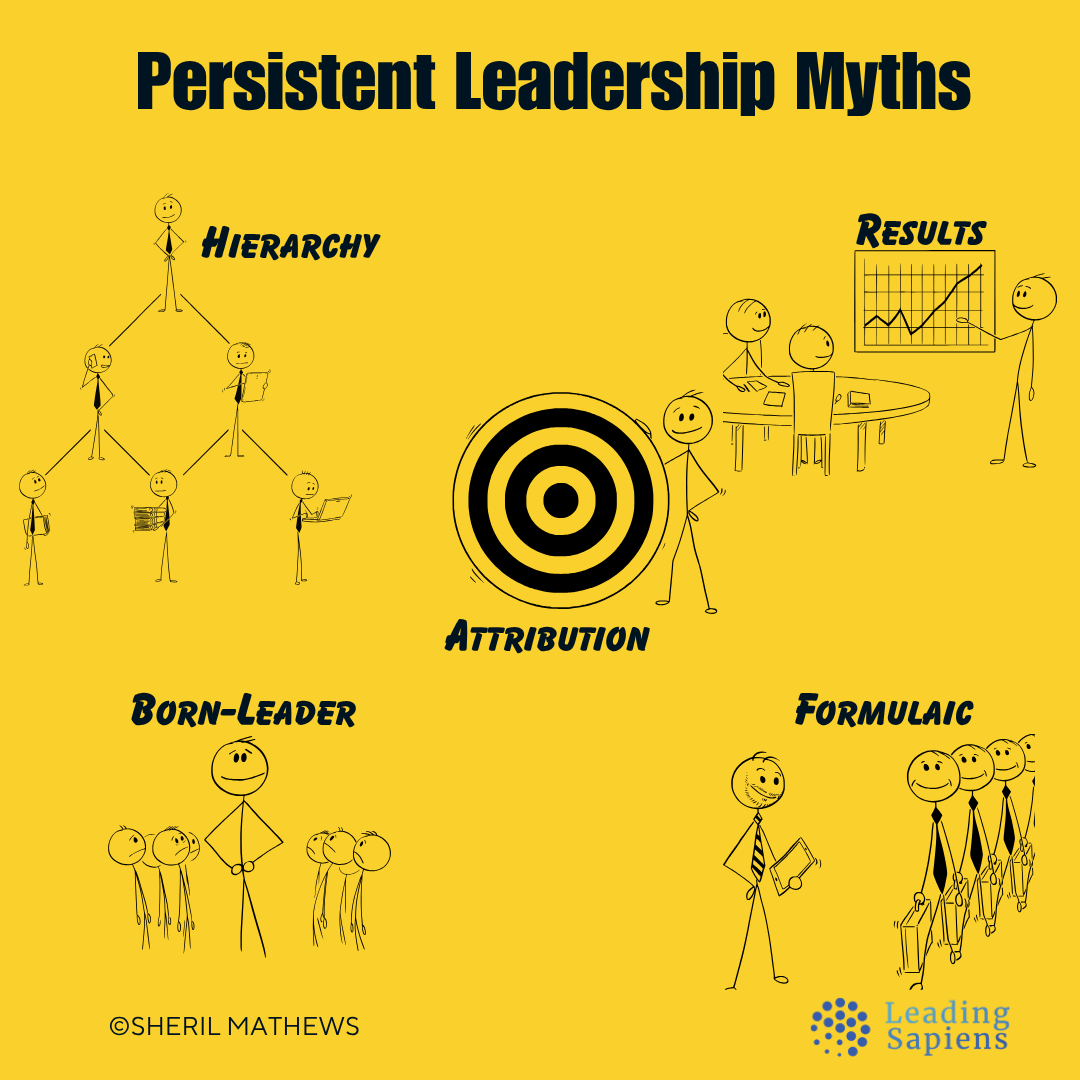

I recently wrote a piece on leadership myths. While writing, I realized these weren’t just organizational myths. They’re also personal myths about careers.

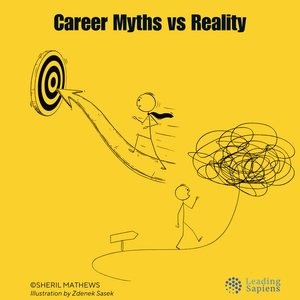

The same cognitive leaps that make us believe in heroic CEOs also lead us to fall for formulaic career paths. The attribution errors that distort leadership evaluation also distort how we evaluate our professional progress. They miss the complexity of what actually drives outcomes and set up the next cycle of disappointment.

Beyond a certain level, disillusionment comes from holding ourselves to the wrong standards; standards that exist more in idealized career advice than in reality.

In this piece, I explore the myths and the machine that generates them, and two ideas I’ve found useful: bounded-accountability and process orientation.

The Career Advice Industrial Complex

Walk into any bookstore's business section and you'll see the same promise repackaged: Follow these seven habits. Think like this billionaire. Career (and leadership) advice becomes a mythology machine: simple stories promising control over complex outcomes.

LinkedIn amplifies this daily with performative success stories that scrub out randomness. Business schools package it into frameworks suggesting careers follow engineering principles. Career coaches sell personalized versions of the same templates.

They're selling the illusion that professional success follows predictable, reproducible patterns.

The mythology persists because it serves everyone involved. Publishers need books that promise transformation. Platforms need content that drives engagement. Coaches need methodologies that justify their fees. Most importantly, we want to believe that someone has cracked the code; that there's a proven path to get where we want to go. This includes yours truly.

But careers aren't engineering problems. They're more like improvisational theater. Equal parts preparation, adaptation, reading the room, and pure chance. The mythology machine can't monetize that complexity, so it ignores it. Instead, it sells you hero's journeys that conveniently ignore all the variables that were equally determinative.

It isn't just that this advice fails. The real tragedy is it misleads by blinding us to the unique aspects of our own circumstances. Busy following someone else's 'playbook', we miss the specific dynamics, constraints, and opportunities in our particular role, company, or industry.

We optimize the wrong variables while the ones that actually matter remain invisible.

Myths That Keep Us Stuck

These myths aren't misconceptions but systematic errors in interpreting professional success and failure. Each of them seems logical in isolation, but together they distort how things really work.

Like all good myths, they persist because they're psychologically irresistible: simple explanations for complex outcomes, that make us feel like someone is in control.

(1) "I Control My Outcomes"

Calling this a myth sounds like heresy in an age of “agency” and “self-made.” But bear with me.

This is the career version of the leadership attribution myth. When you get promoted, it was your strategic thinking. When you get passed over, it was your lack of networking.

We forget that outcomes are embedded in systems much larger than individual performance. Budget cycles, reorgs, and regulatory changes create and destroy opportunities regardless of competence. The person who joined Google in 2003 wasn't necessarily smarter than the one who joined Enron in 2000.

The attribution myth works both ways. In good times, it breeds overconfidence: "I cracked the code." In bad times, it breeds learned helplessness: "I must be doing something wrong." Both responses miss systemic factors that were equally determinative.

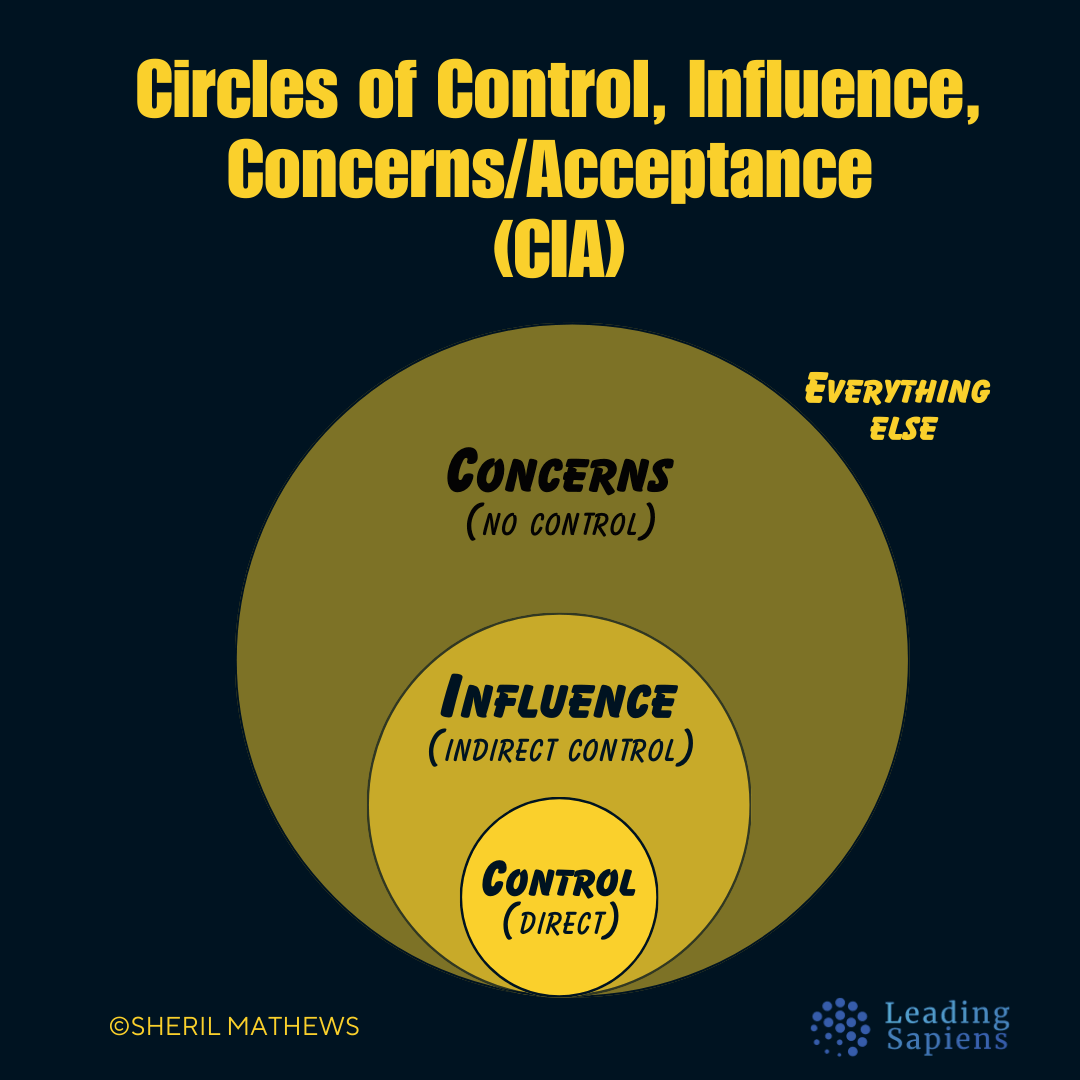

This doesn't mean individual action doesn't matter. It means outcomes result from our actions interacting with forces largely outside our control. Understanding this changes how we position ourselves and interpret setbacks.

This is hard for many high-performers. A better way to think about it is “bounded-accountability” as a counterbalance to the ideal of “extreme ownership”. More on this later.

(2) "There's a Proven Playbook"

This is the career equivalent of the formulaic leadership myth. MBA → consulting → startup equity → executive role. Engineering → product management → VP of Product → CPO. LinkedIn profiles and CEO biographies make it look inevitable: follow this sequence, hit these milestones, achieve this outcome. The logic (albeit a convincing one) is that “success” can be reverse-engineered.

But what looks like a proven playbook is often survivorship and hindsight bias disguised as strategy.

For every visible success story, there are hundreds who followed similar paths and stalled out. The consultant who never made partner or the startup employee whose equity became worthless. Their stories don't get written, so they don't factor into our mental models of "what works."

Even the visible ones are cleaned-up versions that omit the wandering and dead ends that led them there.

The real problem with formulaic thinking is that it makes us rigid when we need to be adaptive. We follow a script when we need to improvise.

Careers are less like algorithms and more like jazz improvisation. You need to know the fundamentals, but you can't pre-plan the performance. And you have to enjoy playing.

(3) "Good Outcomes = Good Strategy"

You switched industries before your old sector faced a major downturn. Meanwhile, your new field is booming. Clearly, you saw the writing on the wall and made a great pivot.

This is the results myth: using outcomes to validate strategy after the fact. Conflating correlation with causation in careers is just as misleading as in leadership evaluation or investing.

When good outcomes validate choices, it creates a false sense of pattern recognition. You attribute success to the wrong variables, while missing other systemic factors. Then you try to replicate those "winning" behaviors in different contexts with disastrous results.

The flip side is equally problematic. When outcomes disappoint, you assume your strategy was flawed. But maybe you made the right bet at the wrong time, or optimized for yesterday’s variables.

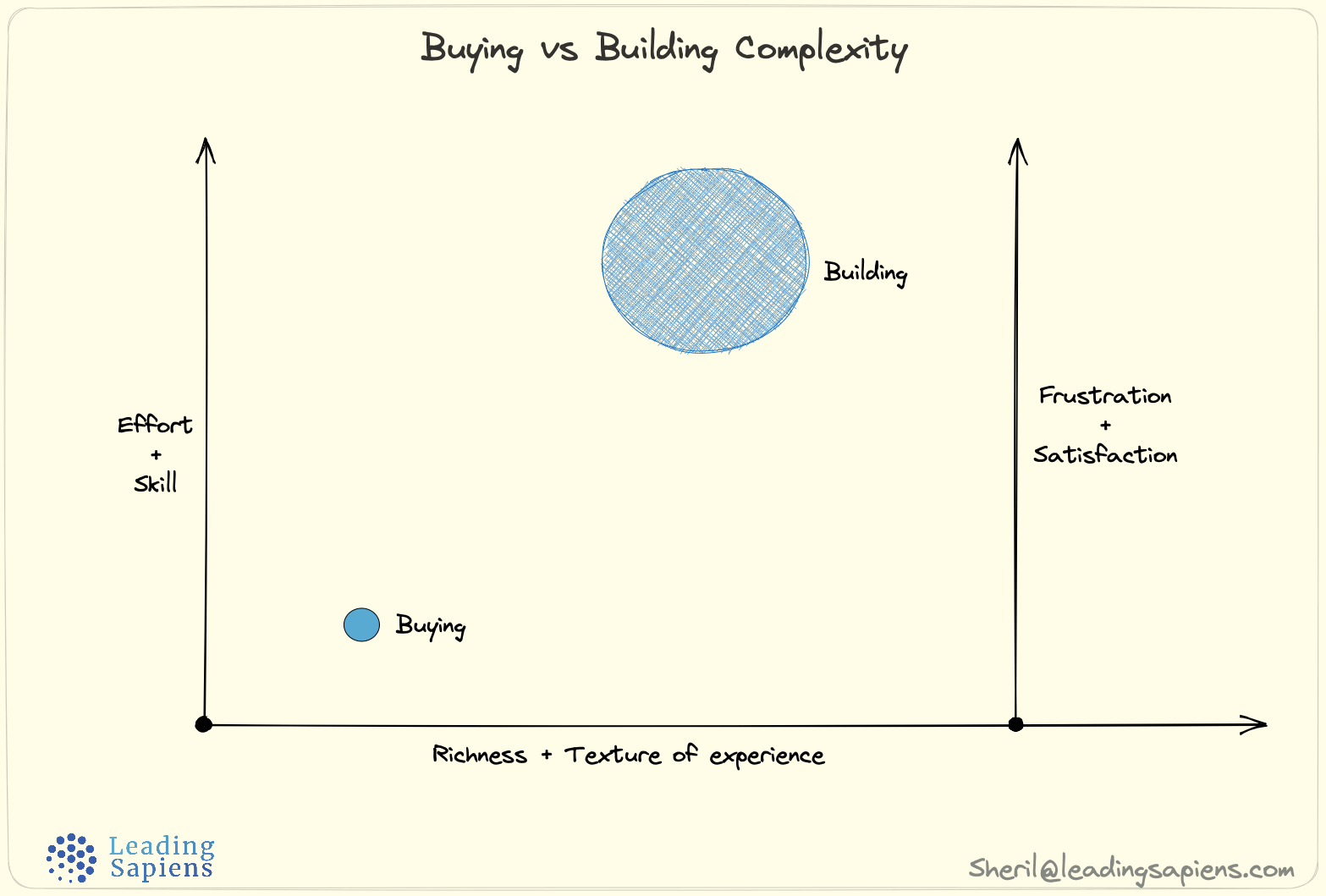

Smart strategy isn't about predicting outcomes but focusing on process and positioning. A process to systematically build capabilities that compound. And positioning that benefits from multiple scenarios regardless of how events unfold.

(4) "Advancement Flows from Above"

You're waiting for senior leadership to notice your contributions. This is the hierarchy myth; the assumption that career progression follows org charts. That someone higher up decides your fate and grants you access to the next level.

It creates a passive mindset of waiting for permission. It's seductive because it feels logical; authority flows downward, so opportunity must too. But influence in organizations is more lateral and networked than hierarchical. Careers are less about climbing ladders and more about building bridges, both internal and external.

The insidious aspect is we attribute too much intelligence to higher ups and don’t trust our own thinking. We assume those with bigger titles have superior judgment, clearer perspective, and deeper insights. How else would they have gotten there?

But organizational hierarchies don’t optimize just for intelligence or wisdom. They also optimize for a complex mix of political skill, risk tolerance, communication, and yes, luck. Sometimes, it’s plain institutional stupidity.

Deference to imagined authority means we second-guess insights that are actually correct. You dismiss your pattern recognition in favor of "strategic thinking" that's just poorly informed decision-making dressed up in executive language. You wait for someone else to validate ideas only you are uniquely positioned to understand.

(5) "Some People Are Built for It"

"She has a way with clients." "He's leadership material." These complimentary phrases imply these abilities are innate, not developed. We don't consciously believe success is purely genetic, but our language and mental models often treat professional capabilities as if they are.

This is the career equivalent of assuming some leaders are born to lead.

What looks like innate talent is usually the compound effect of early exposure, practice, and feedback loops. The person with "great instincts" for sales probably observed client interactions early on. The one with "executive presence" likely had mentors who taught them to project authority.

But we don't see the development process. We only see the polished end result and assume it was always there. This creates a fixed mindset of either you have "it" or you don't. It shows in how quickly we categorize colleagues ("she's more of a big picture thinker") and in our own self-limiting notions.

The truth is messier and more hopeful: most professional skills can be developed if you understand the domain and are willing to put in the work.

Two ideas to tackle these myths

Given their prevalence, what’s the best way to handle these myths? Here are two approaches I’ve found helpful: bounded-accountability and process orientation.

Hyper vs bounded accountability

Luck and timing aren't just external factors but integral to success, especially when defined in conventional terms. Most advice ignores this because it's uncomfortable and uncontrollable.

My point isn't that individual agency doesn't matter. Of course it does. But most of us don't have a problem with taking ownership. Rather, the problem is hyper-accountability.

Hyper‑accountability is assuming you should have controlled everything. It’s the invisible clause under every post‑mortem in your head: “If I were truly competent, I could have prevented this.”

Foresight and omnipotence become part of the job description. You absorb every setback as a personal flaw. Wins are diminished as “just luck,” while losses are catalogued as evidence against yourself. The feedback is skewed: no data point can exonerate you, but every one can indict you.

The trick is to narrow the frame, not widen it. Own what’s legitimately yours, but be precise about what’s outside your circle of control. That’s bounded accountability.

Bounded accountability protects both performance and perspective. Without it, your capacity gets spent retrofitting control onto things that were never controllable. With it, we retain agency without assuming omnipotence.

You take action while acknowledging the scale of the system you’re operating in. It acknowledges that agency operates within constraints and opportunities we don’t control.

Succeeding doesn't mean eliminating luck from the equation. Instead, it's positioning to benefit from good fortune, and even more importantly, surviving and thriving amidst the inevitable bad breaks. And thriving requires appreciating the nuance between hyper-accountability and bounded-accountability.

The ordinariness of extraordinary outcomes

Strip away the mythology and careers look disappointingly mundane. No dramatic pivots, visionary moments, or sudden flashes of brilliance. Just the accumulated compound effect of consistent actions over time, most of which feel insignificant in the moment.

This means showing up and “doing the work” day after day, year after year. You only notice the shape in hindsight, and even then, it looks less like a strategy and more like a sedimentary buildup of small, nearly invisible actions.

This mundanity is unsatisfying to our narrative-hungry brains. It feels like nothing’s happening. So we over-index on visible milestones (outcomes) and ignore the slow work (process) that actually creates the conditions for those outcomes.

Embracing this ordinariness is an edge. Most people don’t fail due to one bad move but because they can’t survive the long, dull, low-reward stretches in between. We burn out chasing “proof points” instead of compounding small wins and pacing ourselves for the long run.

The “big break” is rarely the beginning of the story. It’s often the first visible tile in a mosaic we’ve been assembling for years.

In closing

The career advice industrial complex sells a seductive lie: with the right playbook, we can game the system and speed things up. Ironically, by clinging to these myths, we make careers harder than they need to be. What was meant to empower ends up straightjacketing us.

But once you stop fighting complexity and start working with it, what felt like stagnation starts to look like optimizing for the wrong game. The real challenge isn’t finding a “proven” roadmap, but cultivating a different way of engaging with the game.

In the end, the most damaging career myth is the idea that there's a "right" way to do it.

The most satisfying ventures aren’t those that follow a prescribed path, but ones that create new paths that are uniquely ours.

Related Reading