Increasing entropy is the natural state of the universe — everything disintegrates to lower levels of order, especially living things. But when it comes to human choices, we are always moving toward higher states of order, or what some might call “taste”. Our tastes tend to evolve over time, and become more nuanced and complex.

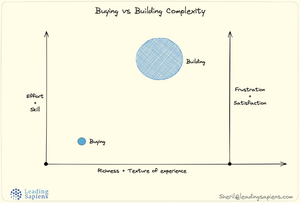

But there are two fundamentally disparate ways of reaching this higher level of taste: buying vs building. Is one necessarily better than the other? What is more sustained and longer lasting?

Moving towards increasing complexity

One way to meet this need for higher, more evolved taste, is to buy more and more refined things. It’s what I call buying your way into increasing complexity. We are trying to get to that next level of complexity through “arbitration" using money, rather than working our way towards it.

To illustrate, consider the example of a Lego enthusiast. At some point, they will reach a fork in the road: buy a pre-designed, pre-made complex kit, or design one themselves and build it out. As you can imagine, there are various tiers and nuances to this.

Increasing levels of complexity and taste are also a social signaling method: think about a gas-station bought wine vs owning a dedicated wine cellar vs owning an entire vineyard.

More examples of buying our way into increasing complexity:

- Buying a fancy blog design vs coding it yourself.

- Buying an expensive car or home vs refurbishing it yourself.

- Buying a room full of books vs reading them vs learning from them vs writing one.

- Buying a meal at a restaurant vs cooking a meal from locally sourced produce. Bear in mind, this is fractal — we typically introduce tiers of bought complexity here. E.g. a hole in the wall place vs a Michelin star restaurant.

- Writing an article yourself vs paying someone to do it for you, or using AI.

I realize many of the building approaches are simply not practical. These are not perfect examples, but they illustrate the basic idea: in one we are buying complexity, whereas in the other we are building up to higher levels of complexity.

How they are different

When we exchange money for increasing complexity, we are often trying to bypass, and hopefully avoid, three things: pain, uncertainty, and effort. [3] We are attempting to go directly to what we want: satisfaction, ownership, and enjoyment.

Except, the associated feelings tend to be fleeting and temporary. There's a hollow ring to them. And because there was no “investment” on our part outside the money, we move on to bigger and better things, thus re-starting the hedonic treadmill.

Here are some additional characteristic differences between the two:

Investment and return dimensions. When buying complexity, we invest money to get emotional and psychic returns. In building complexity, we invest emotional and psychic efforts to yield returns in the same dimensions.

Predictability. Buying is fast and efficient, while building can be slow, painful, and frustrating. Progress follows an expected curve in one, while in the other it's not as predictable.

Dose effectiveness. Building tends to stay consistent in its positive effects, whereas buying requires to "up" it with quantity, novelty, or frequency.

After effects. Buying tends to leave you empty after the initial high, whereas building, while often frustrating, has longer lasting positive effects, even without accounting for obviously positive effects like building skills.

Money. At least in terms of skills, money becomes less of a factor when building. Skill becomes a leveling factor — billionaires can't necessarily buy a skill for themselves.

Experience of time. When engrossed in something that requires both psychic and emotional investment, time flies. We, in fact, become time itself. In contrast, trading time for money, without any engagement, is the complete opposite. Every moment becomes drudgery.

The pleasure of process

In building complexity, the focus is on the pleasure of process, rather than the pleasure of outcome. One is short-lasting, while the other has longevity and builds on itself.

To be complicated is to take pleasure in the process rather than pleasure in the outcome.

…To take pleasure in the process is to understand what an Ithaka means.

– Karl Weick [2]

Weick is referencing C.P. Cavafy’s classic poem Ithaka (partial excerpt below):

As you set out for Ithaka

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

…

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn't have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Cavafy’s poem has parallels to the ancient Chinese curse: “May you get everything you wish, right away, and all at once”.

Building your way to complexity, and the pleasure of process, invariably means embracing effort, which runs counter to what we usually think of human behavior: minimizing pain, maximizing comfort. But these counter-intuitive notions about effort can be found in the latest social psychology research as well.

Dan Ariely [1] explains:

In light of these findings, we might want to revisit our ideas about effort and relaxation. The simple economic model of labor states that we are like rats in a maze; any effort we put into doing something removes us from our comfort zone, creating undesirable effort, frustration, and stress. If we buy into this model, it means that our paths to maximize our enjoyment in life should focus on trying to avoid work and increase our immediate relaxation. That’s probably why many people think that the ideal vacation involves lying lazily on an exotic beach and being served mojitos.

Similarly, we think we will not enjoy assembling furniture, so we buy the ready-made version. We want to enjoy movies in surround sound, but we imagine the stress involved in trying to connect a four-speaker stereo system to a television, so we hire somebody else do it for us. We like sitting in a garden but don’t want to get sweaty and dirty digging up a garden space or mowing the lawn, so we pay a gardener to cut the grass and plant some flowers. We want to enjoy a nice meal, but shopping and cooking are too much trouble, so we eat out or just pop something into the microwave.

Sadly, in surrendering our effort in these activities, we gain relaxation, but we may actually give up a lot of deep enjoyment because, in fact, it’s often effort that ultimately creates long-term satisfaction. Of course, it might be that others can do better wiring work or gardening (in my case, this is certainly true), but you might ask yourself, “How much more will I enjoy my new television/stereo setup/garden/meal after I work on it?” If you suspect you would enjoy it more, maybe those are cases where investing more effort will pay off.

A checklist to differentiate

How do we know if we are building or buying complexity? Here are some general pointers:

- Can it be exchanged for money?

- Does it require building a skill? Even billionaires cannot buy skill. You have to learn it.

- Does it require emotional and psychic investment?

- Are you on an even playing field (for the most part) with billionaires?

- Does it require time, attention, effort?

- Is it instantaneous? Or does it evolve?

- Direct vs oblique — are you trying to directly “acquire” satisfaction, or does it follow as a result of?

- Does it involve pain and uncertainty?

- Does it need sustained commitment?

Sources

- The Upside of Irrationality by Dan Ariely

- Social Psychology of Organizing by Karl Weick

- The Tools by Phil Stutz, Barry Michels