Most of us have facets of our lives where things are just not up to the mark. We’d like things to be different, but somehow it hasn’t panned out. And equally likely, we already know what needs to be done and how to go about it.

Yet, we falter. Why?

To state the obvious: knowledge per se doesn’t trigger action. Knowing what to do and actually doing what it takes in the heat of action are worlds apart. Maybe because it’s obvious, we don’t give much thought to it.

In coaching, I’ve found that paying closer attention to differences between “the one who plans” vs “the one who executes” pays rich dividends. Albert Bandura — the foremost researcher on self-efficacy (confidence) — called these the “decisional self” and the “performative self”. [1]

If the decisional self is the architect, the performative self is the contractor who must build the structure in a messy, unpredictable reality.

The goal then is twofold. We have to ensure that:

- The decisional self is bold enough to consider high-value options.

- And the performative self is resilient enough to execute them.

Recognizing and accounting for these two selves goes a long way in ensuring we stick to our most ambitious goals.

The Decisional Self

The decisional self is concerned with the slate of options available to us. It’s the one who gathers information, weighs potential costs and benefits, and envisions likely consequences of various paths.

The first major theme of the decisional self is self-censorship.

Not only is the decisional self a choice-maker, it’s also an internal architect who determines which possibilities are even allowed to enter our field of vision. It’s a restrictive filter that only presents the options our self-belief allows us to see. It’s the architect who only draws rooms it believes we are capable of entering.

Bandura notes:

People simply eliminate from consideration occupations they believe to be beyond their capabilities, however attractive the occupations may be.

We do not simply weigh all available paths; we "rapidly eliminate entire classes of options on self-efficacy grounds" without even bothering to analyze their potential costs or benefits. If you judge yourself as inefficacious in something—whether it’s negotiation or a new technology—you eliminate those options entirely from your range of possibilities.

This is worth pausing over.

Whatever your goals are, consider that there were an entire slew of them you didn’t even bother considering simply because you didn’t think you can pull it off. Usually, we don’t question this dynamic. It’s simply accepted as a given.

To counter this tendency, remember that our internal filters are often based on “faulty self-knowledge" and "illusory inefficacy" rather than actual ability.

When we believe we lack the power to produce a result, we lose the incentive to even consider the attempt. So, it’s useful to consciously re-examine "foreclosed options”—things we dismissed not because they were irrational, but because we didn’t think we have what it takes.

The second major theme is how we “structure” our aspirations.

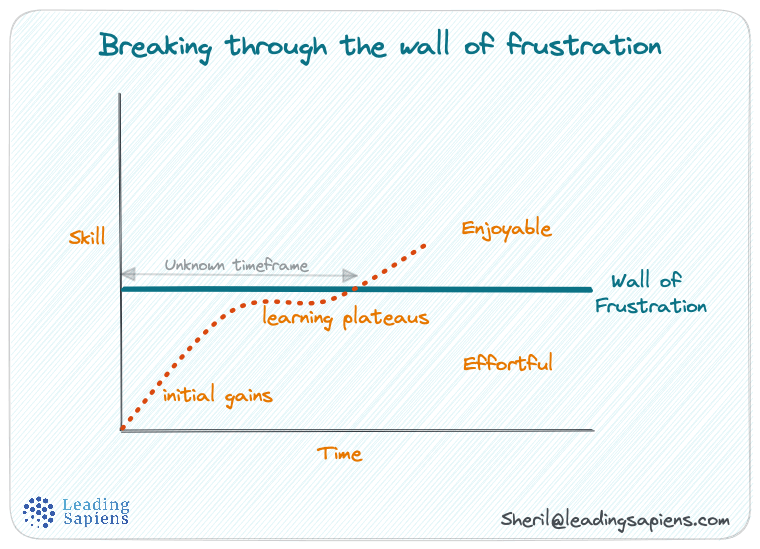

Long-range goals provide direction, but they are too far removed in time to act as current motivators. When the decisional self only focuses on the distant peak, it risks getting demoralized through the wide disparity between current state and the final standard.

The most effective way to empower the decisional self is to structure the journey into attainable subgoals which provide:

- Clear markers of our growing capability.

- Immediate incentives that build the commitment to keep going.

- Corrective data that helps identify and adjust strategies in real-time.

The third major theme of the decisional self is how we account for failure.

Those with high self-efficacy use the decisional self to visualize successful outcomes that provide positive guides for performance. Conversely, those plagued by self-doubt dwell on potential failures and imagine difficulties to be more formidable than they truly are.

With low decisional efficacy we procrastinate or spend inordinate amounts of time gathering information for "self-protective purposes". We aren't seeking clarity, instead we are building a shield against the risk of being wrong.

The decisional self must weigh costs and benefits, yet this process is typically inefficient, even illogical. We act (or don’t act) because of our beliefs about what we can do as much as on our beliefs about the likely outcomes.

The Performative Self

There’s an entire genre of books, departments, and gurus who focus exclusively on “decision-making”.

But focusing too much on making the perfect decision can make us think that once we’ve made our choice, we’re done. We think that if we weigh the options, consider the costs, and pick a path, the hard part is over. That if we think something is worth it, we’ll take the necessary actions.

In reality, though, a decision is merely an intention. And intentions are not actions. The decisional self may form an intention (e.g., "I want to quit smoking"), but this intention is merely a goal. Getting there requires a performative self to survive the day-to-day.

As Bandura noted:

A psychology of decision-making requires a psychology of action.

Without a robust performative self, even the most brilliant decisions remain idle fantasies because we doubt if we can muster the resources needed to persevere through the inevitable obstacles of setbacks during implementation. We remain stuck in analysis and preparation.

That’s why talent alone cannot predict success. We’ve all seen capable individuals falter, even when they know full well what to do. The performative self is the bridge that connects knowledge and action. An athlete or manager may have excellent mechanics but fail to behave optimally because they doubt their performative self’s ability to improvise when the going gets unpredictable and stressful.

The performative self also determines how hard we work and how long we keep going.

The strength of the performative self's conviction determines whether we even try to cope with a given situation. When faced with obstacles, setbacks, or failures, those with a robust performative self "redouble their effort to master the challenges," while those who doubt their capabilities "slacken their efforts, give up, or settle for mediocre solutions".

In this sense, the performative self is the seat of resilience. It determines whether we read a setback as a sign of personal deficiency—which stifles performance—or as instructive feedback for enhancing our capabilities.

Strengthening the Performative Self

Given the importance of the performative self in closing the knowing-doing gap, below are some strategies to strengthen it.

1. Do hard things

The decisional self is all about “outcome expectations”: the belief that a certain action will bring about a desired result. But the performative self is all about “efficacy expectations”: the conviction that we can actually pull off the behaviors needed.

In other words, we cannot simply talk the performative self into action; we must provide action-based evidence.

Mastery experiences, like conquering tough challenges, are the most powerful proof that we’ve got what it takes.

Some pointers:

- To succeed at long-term projects, it’s important to focus on small, incremental progress towards the larger goal. These small wins build confidence and motivation, making it easier to take the next step.

- On the other hand, success that comes too easily can be fragile. It’s crucial to develop a resilient mindset by consistently overcoming significant obstacles. If we only experience quick results, it’s easy to lose hope when faced with a setback.

- When learning new skills, it’s natural to seek help initially. However, we have to eventually execute the skill independently. Achieving these “independent successes” removes any doubts about our abilities.

2. Scaffolding for self-management

The performative self often fails because we’re not psychologically prepared for the long run. Unlike outcomes, execution is not a fixed one-time act but an ongoing rhythm of day-to-day continuous improvisation.

This requires better goals, systems for tracking these goals, and processing setbacks:

- It's hard to stay consistent without tracking results. However, the performative self is easily undermined by "selective attention to poorer performances". Accuracy requires an emphasis on what’s working as well to ensure successes are noticed, remembered, and build upon.

- The performative self is highly sensitive to how feedback is framed. Evaluations that focus on progress underscore capability, whereas those focusing on shortfalls from a distant goal highlight deficiencies.

- Proficient action requires the performative self to remain "task-oriented" rather than "self-diagnostic". This means treating mistakes as useful feedback rather than a verdict on talent.

3. Thought hygiene

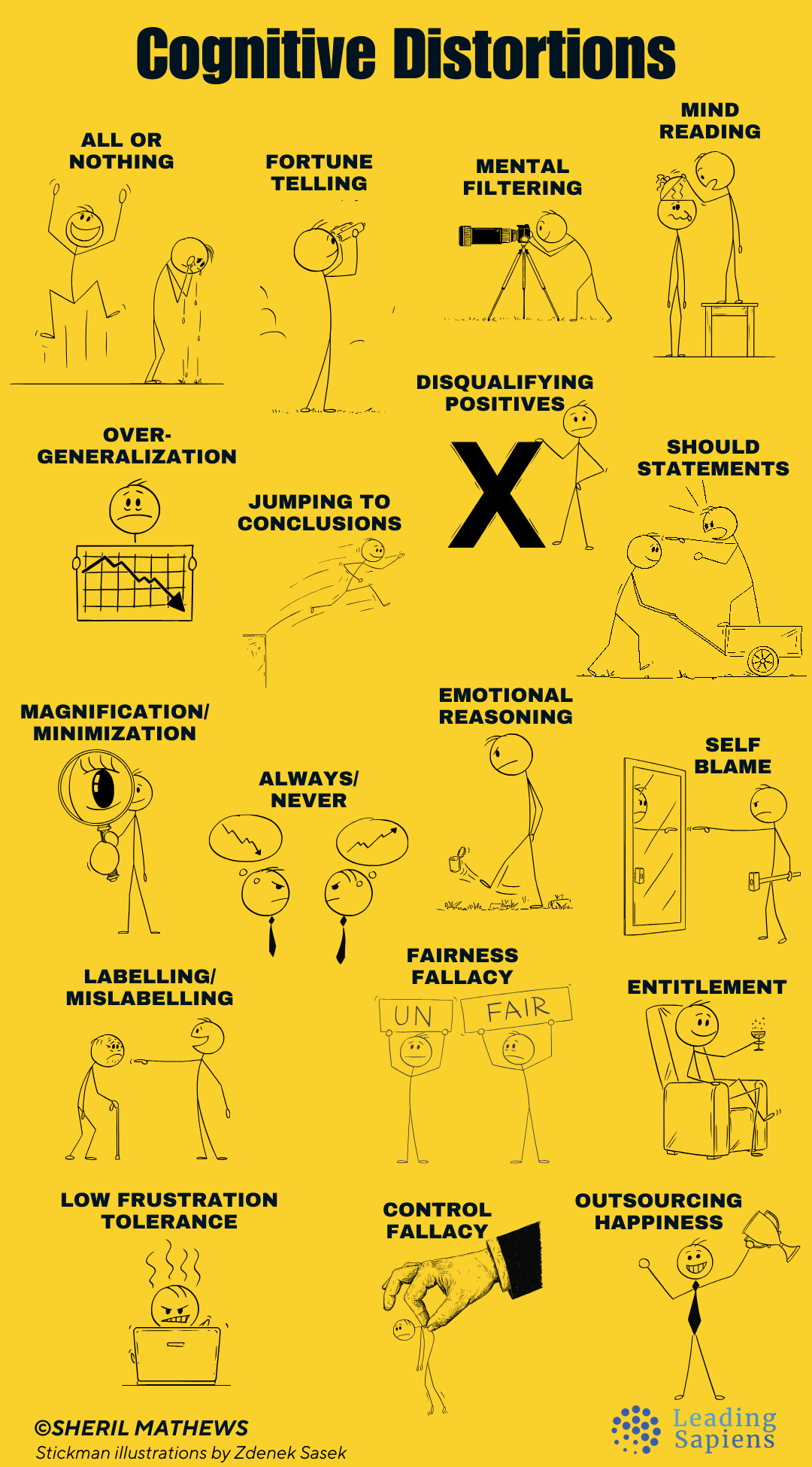

A common reason the performative self fails to meet the decisional self's standards is the intrusion of unhelpful thought patterns. When we dwell on personal deficiencies or imagine potential difficulties as more formidable than they actually are, we divert attention from the task to our shortcomings.

To get better at execution, we must develop thought control efficacy. Two practices I can personally vouch for are:

- Attention training practices like meditation.

- And minimizing cognitive distortions.

4. Re-interpreting physical cues

The performative self often misreads biological signals. In stressful situations, a weak performative self reads fatigue, aches, and pains as proof of physical inefficacy. In contrast, a strong performative self interprets the same physiological arousal as an energizing sign that they are ready for action.

Accomplished actors do not view nervousness as personal incapability, but as a "normative situational reaction".

To align the performative self with the decisional self, we must learn to view visceral physical cues not as an ominous sign of vulnerability, but as the biological engine being revved for the task at hand.

In closing

Only when the performative self believes in its capability can the decisional self's choices be executed and realized in the real world. As Bandura notes, the performative self is the "existential commitment to one’s own capacity to build a worthwhile life".

When we strengthen it, not only do we improve performance, we increase the likelihood of our intentions becoming lived realities.

Related Reading

Sources

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control.

- Bandura, A. (2009). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior.

- Peltier, B. (2010). The Psychology of Executive Coaching: Theory and Application.