Managerial effectiveness often hinges on how well their unit interacts not just internally but externally as well. In one definition, leadership and management is essentially about orchestrating the flow of information and influence.

In his magnum-opus Managing, Henry Mintzberg uses the hydrological analogy of channels, valves, sieves, dams, sponges, hoses, and drips, to highlight this dynamic:

Managers are not just channels through which pass information and influence; they are also valves in these channels, which control what gets passed on, and how… managers are gatekeepers and buffers in the flow of influence.

To appreciate the importance of this, consider five ways by which managers can get it wrong:

Some managers are sieves who let influence flow too easily into their unit. This can drive their reports crazy, forcing them to respond to every pressure. We see this commonly these days when the demands of stock market analysts cause the chief executives of publicly traded companies to force everyone to manage for short-term performance.

Other managers are dams who block out too much of the external influence—for example, from customers asking for product changes. This may protect the people inside the unit, but in so doing detaches them from the outside world—and external support.

Then there are the sponges—managers who absorb most of the pressures themselves. This may be appreciated by others, but it is only a matter of time before these managers burn themselves out. I have seen this in some chiefs of hospital departments who are overprotective of the physicians.

Managers acting as hoses instead put great pressure on the people outside, who may as a consequence become angry and less inclined to cooperate. This is common when a company squeezes its suppliers excessively.

Finally, there are the drips, who exert too little pressure on the people outside, so that the needs of the unit are not well represented. Examples are those managers who ask too little of their suppliers and so get taken advantage of.

The effective manager may act in each of these ways some of the time but does not allow any of them to dominate all of the time. In other words, managing on the edges—the boundaries between the unit and its context—is a tricky business: every unit has to be protected, responsive, and aggressive, depending on the circumstances.

All of us fall into patterns over time. This is a great framework to think through biases and adjust for them. Which one of these managing styles is most like yours? What are you skewed towards? How can you make adjustments?

One way leaders regulate information and influence is through effective conversations and managing the context.

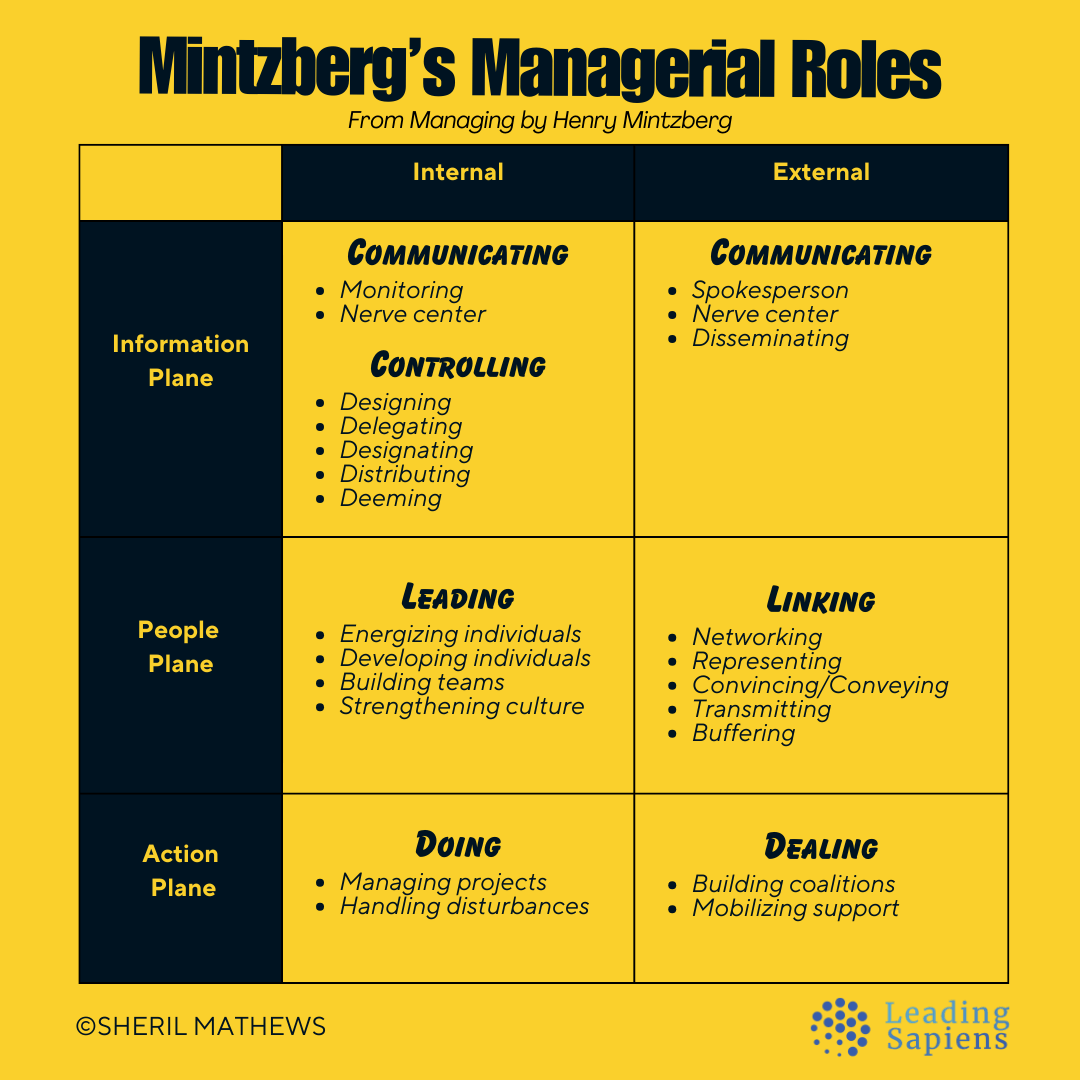

Mintzberg's book is a tour de force on all aspects of leading and managing and should be required reading at all levels. For a more comprehensive look at Mintzberg's managerial roles and managing model check out: