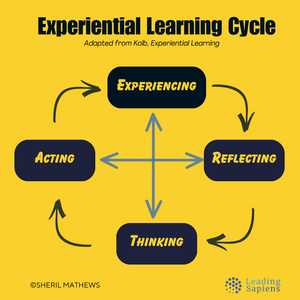

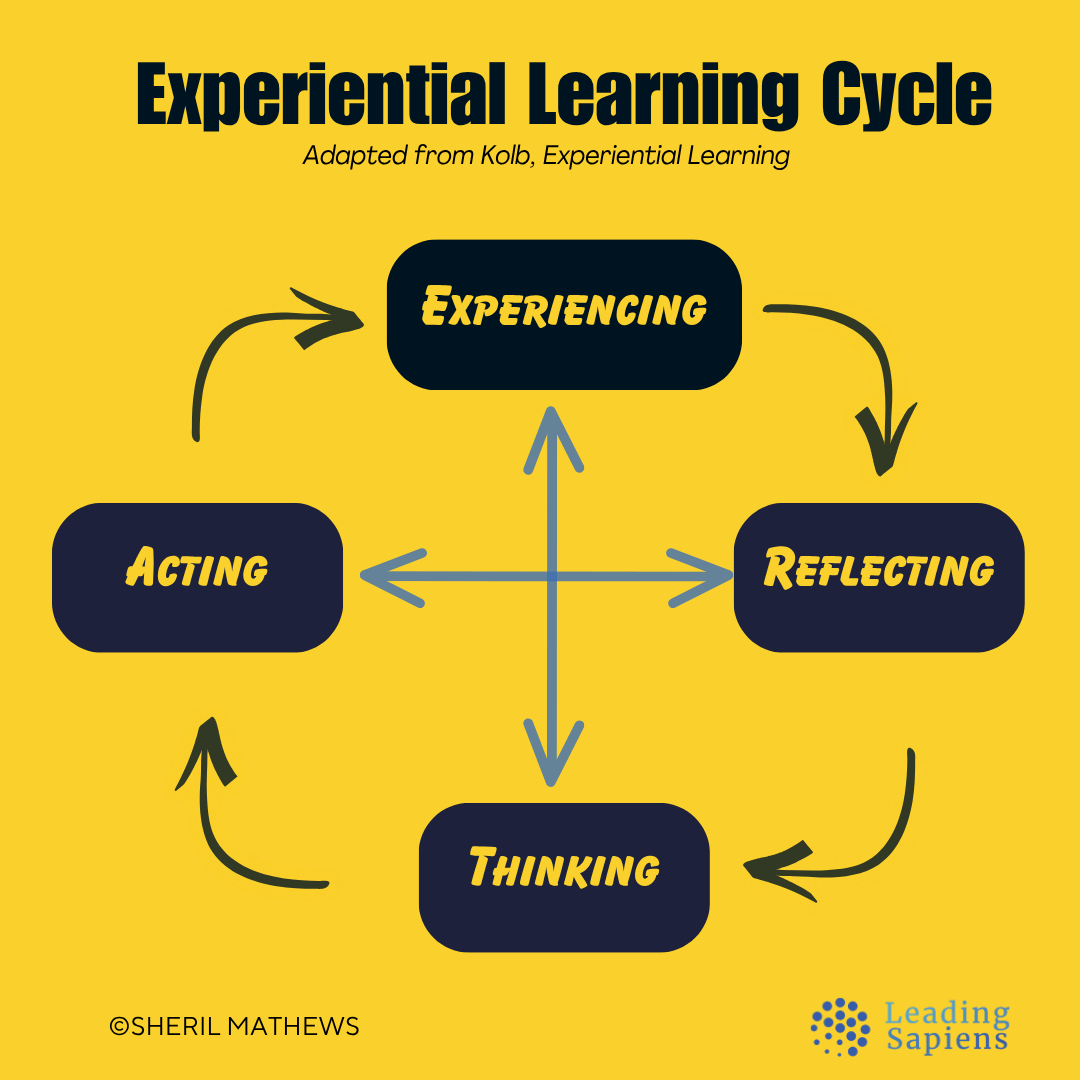

It’s easy to assume that you learn from all experiences. Not always. Those who adapt and learn the fastest are actually using a deeper process that turns experience into compounded learning. David Kolb called this the experiential learning cycle thats consists of Concrete Experience (experiencing), Reflective Observation(reflecting), Abstract Conceptualization (thinking), and Active Experimentation(acting).

While usually depicted as a sequence, Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is much more powerful and nuanced. The key insight is that learning happens in the tensions between opposites—between acting and reflecting, between experiencing and thinking. Instead of a loop you complete once, it's a spiral that changes you with each turn, subtly altering your approach each time.

In this piece I take a closer look at Kolb’s experiential learning cycle and why understanding the tensions is key to leadership sensemaking.

The basis of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is a synthesis of three distinct but converging streams of thought from John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, and Jean Piaget. Each brought a different lens to the same underlying question: How can we actually learn from experience in a way that changes how we think, feel, and act?

Turning Impulse into Purpose (Dewey)

John Dewey saw learning as a developmental process where raw impulses and desires are refined into purposeful action through observation, reflection, and judgment. He argued for postponing immediate action until we’ve examined the situation.

In his view, experience isn’t just something that happens to us; it’s the raw material we shape through thoughtful engagement. The “pause” between impulse and action is where learning transforms future possibilities.

Feedback Loops (Lewin)

Kurt Lewin’s action research made here-and-now experience the starting point. His big contribution was the emphasis on feedback as the lifeblood of learning. Without it, we fall into the two traps of acting without enough information, or drowning in analysis without acting. Instead of just moving forward, it’s making sure each move is informed by reality, not assumption.

Assimilation and Accommodation (Piaget)

Piaget approached learning from the cognitive standpoint. We either assimilate — fit new experiences into existing mental models — or accommodate — adjust our mental models to fit new experiences. Learning thrives in the tension between the two.

When accommodation dominates, we mold ourselves entirely to circumstances (imitation). When assimilation dominates, we impose our own concepts without adjusting to reality (play). True growth requires a balance, which over time goes from concrete, immediate engagement to more abstract and reflective modes of thought.

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle

Kolb brought together all three strands in what he called the experiential learning cycle. It has four modes but none of them is sufficient on its own. Each adds something the others don’t.

- Experiencing or Concrete Experience (CE): direct, lived events — the meeting that went sideways, the decision that surprised you, the conversation you can’t shake. This is raw contact with reality before interpretation starts.

- Reflecting or Reflective Observation (RO): stepping back to look at what happened, how it unfolded, and what stands out. This is where you notice patterns, contradictions, and possible meanings.

- Thinking or Abstract Conceptualization (AC): translating those observations into ideas, principles, hypotheses, or mental models. You build an explanation for what happened and why, so it can apply beyond the specific moment.

- Acting or Active Experimentation (AE): taking those ideas back into the field. You try something new — a different approach, a revised frame, a new behavior — and generate fresh experience.

That new experience becomes the start of the next cycle. Rather than a loop you complete once, it’s an ongoing rhythm: experience → reflection → understanding → action → experience…

Two aspects often misunderstood are worth mentioning:

First, in practice, the cycle isn’t sequential. You don’t go through experiencing → reflecting → thinking → acting in a tidy order. Instead, we move between modes depending on what the moment demands. Sometimes you’re reflecting first while in others you jump straight into action. Sometimes a concept comes before the experience that later confirms or challenges it.

Second, the cycle only works if you move through all four modes. You may not touch each mode in every situation, but growth requires eventually passing through all of them. When one mode is overused— acting without reflecting, or theorizing without testing — the cycle is stuck in a loop around your comfort zone.

The value of Kolb’s cycle is that it gives a complete map of how learning actually happens. It shows that development is a movement among very different forms of engagement: being in the experience, stepping out of it, making sense of it, and re-entering it with intention.

This is why two people can go through the same events and come out with completely different levels of growth. One simply had experiences while the other matured through cycles.

The Two Tensions

Kolb was clear that experiential learning isn’t a sequence of steps but a dialectical process – each mode has an opposite that counterbalances it. Real learning emerges not from choosing one over the other, but from engaging the tension between them. These tensions come from how we make sense of the world: whether we meet experience directly or hold it at a distance, pause to interpret or intervene to shape what happens next.

Kolb described these as movements between opposing ways of knowing. Each pole offers something indispensable but also becomes distorting when relied on exclusively. The work of learning lies in shifting across these opposites over time, allowing each to challenge, correct, and deepen the other.

In this sense, the cycle isn’t merely a model of learning but a description of psychological flexibility required to grow.

Experiencing vs Thinking

At one end is Concrete Experience (experiencing): immersion in the moment, engaging directly with people, situations, and events. It’s sensory, emotional, and specific. At the other end is Abstract Conceptualization (thinking): stepping back, stripping away the details, and building a mental model or theory.

The tension is between being in it and standing apart from it. Rely too much on concrete experience and you risk being swept along by events without perspective. Lean too far into abstraction, and you drift into theory detached from reality. Learning requires moving between immediacy and distance, letting each inform and correct the other.

Ron Heifetz called this being on the balcony vs on the dance-floor.

Observation vs Experimentation

The second tension is between Reflective Observation (reflecting): watching, listening, and considering multiple perspectives, and Active Experimentation (acting): intervening, making a change, and seeing what happens.

Reflection without action leads to analysis paralysis; elegant insights that never touch the ground. Action without reflection leads to busy ineffectiveness; energy spent without learning from the results. The skill is in knowing when to pause and when to move; when to look for patterns and when to test them.

Why the Tensions Matter

In practice, we can’t occupy both ends of either spectrum at once. You can’t be fully immersed and fully detached in the same moment. Or be deep in reflection and fully committed to action simultaneously. The cycle works because it pushes you to shift modes over time, touching all the bases so you don’t get stuck in the one that feels most natural.

The idea isn’t a perfect balance but a kind of adaptive rhythm. Some situations call for rapid movement between modes while others demand staying in one mode longer than is comfortable.

Learning is not about finding one “best” way, but about becoming fluent across the full range.

Applying the Learning Cycle

The real value of Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is in using it as a self-audit tool. The key is to recognize your default mode and learn to deliberately shift into the ones you tend to avoid.

Most of us have a “home base” in the cycle—a mode we inhabit without thinking. It feels comfortable, natural, and productive… right up until it limits us. The fastest way to speed up your learning is to spot that bias and lean into the opposite mode.

If Experience is your preference

You learn by being in the thick of things — in the room, on the call, close enough to feel the energy of the moment. Your instincts come from direct contact with what’s happening, not from standing back and theorizing about it.

The risk is that you move from one situation to the next so quickly that nothing accumulates. The learning stays local and episodic because you haven’t stopped long enough to identify the underlying pattern.

The fix is to pause before you act again. Step into Abstract Conceptualization (thinking) long enough to articulate the principle behind what just happened. When you can explain the pattern, learning becomes transferable rather than situational.

If Thinking is your preference

You learn by thinking things through: framing problems, building models, shaping explanations. You gravitate toward the conceptual layer because that’s where things feel manageable and coherent.

The risk is of drifting upward into theory and losing contact with reality. The map becomes more compelling than the territory.

The fix is to return to Concrete Experience. Sit in on the meeting; watch the process unfold. Stay close to the mess and unpredictability of real events; it will tune your concepts more precisely than another round of analysis ever could.

Related: MBWA: Managing by Wandering Around

If Reflection is your preference

You learn by slowing down — noticing patterns, comparing perspectives, taking stock before deciding what to do. You see what others miss because you give yourself time to interpret.

The risk here is that clarity becomes a requirement rather than an advantage. You wait for the perfect angle of understanding, and in the waiting, opportunities pass.

You mitigate this by leaning into Active Experimentation (acting). Pick one interpretation and test it in the field before it's fully baked. The feedback will sharpen your insight far more quickly than continued contemplation.

Related pieces: Action creates clarity, small wins

If Action is your preference

You learn by doing — trying things, adjusting on the fly, moving ideas into action before they calcify. You generate momentum and learn through forward motion.

The risk is that speed becomes a substitute for depth. You move from one action to the next so quickly that the learning evaporates between steps.

Mitigate it by stopping long enough to enter Reflective Observation (reflecting). Ask yourself, “What did that last action teach me?” Pausing is not the enemy of momentum — it’s what allows action to accumulate into capability.

Think of the four modes as muscles. You’ll always have a dominant one, but strength comes from agility with all four. In any given situation, ask yourself: Which mode am I in right now? Which one am I avoiding? Then make the shift especially when it feels least natural. That’s how the cycle starts becoming a practice and discipline.

Experiential Learning Cycle: A Tool for Leadership Sensemaking

Leadership roles are often a race against time. You’re expected to make decisions quickly, navigate competing priorities, and keep moving in changing conditions Under that kind of pressure, it’s easy retreat to your default mode in the experiential learning cycle.

Some double down on action: moving fast, making calls, and staying ahead through momentum. While others retreat into reflection: gathering more data, weighing perspectives, thinking it through before risking a move. Although both tendencies have value, they can also trap you.

Kolb’s cycle offers a way out of these traps. It gives you a map for where you are in your thinking and acting, and more importantly, where you’re not. The cycle doesn’t replace judgment but instead sharpens it by making the gaps visible.

In the middle of a complex decision or a tense situation, ask:

- Am I close enough to the reality (Concrete Experience), or am I working off second-hand reports and proxies?

- Have I paused long enough to reflect (Reflective Observation/reflecting), or am I charging ahead?

- Have I framed the problem clearly (Abstract Conceptualization/thinking), or am I improvising without a model?

- Have I tested my assumptions (Active Experimentation/acting), or am I clinging to a plan that hasn’t met reality yet?

Even a 30-second scan through these questions can change your next action. It can stop you from reflexively operating in the mode you prefer and pull you toward the one that the situation actually needs. Having a discipline like this matters for avoiding blindspots, faster adaptation, and better judgement under pressure.

The cycle is akin to a real-time instrument panel for your learning and leadership. The next time you’re facing a decision, a problem, or even an unexpected success, run the cycle in your head and ask:

- Which mode am I in right now?

- Which mode am I avoiding?

- What would happen if I shifted?

Kolb’s model is a rhythm to master. The more fluently you move through it, the more each experience becomes not just something that happened, but something that changes how you see, think, and act. Aka leadership wisdom and sensemaking.

Related Reading