The Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition is one of the most enduring explanations of how human beings develop mastery. We think of experts as people with all the answers — those who can explain, justify, and systematize what they know. But in practice, the most skilled performers often can’t explain their brilliance. Their knowledge shows up in how they see, not always in what they say.

This intuitive side of mastery is almost invisible and routinely misunderstood in organizations. This is particularly relevant in today's push towards AI and where humans still have an advantage. The Dreyfus Model shows how we improve, and why real expertise looks different from what we usually expect.

In a followup piece, I'll use the model to make the case why AI will not be replacing competent leadership any time soon.

On this page:

- The easy promise of expertise

- Origins of the model

- Five Stages of the Dreyfus Model

- Key Concepts and Underlying Dynamics

- Why the Dreyfus Model is still relevant

- Dreyfus Model - An Example

- Related Reading on Learning

The easy promise of expertise

Mathematical formalizers wish to treat matters of intuition mathematically, and make themselves ridiculous.. . . The mind. . . does it tacitly, naturally, and without technical rules.

Blaise Pascal in Pensees (1670) [1]

I'm not sure about Pascal, but we surely live in a time when mastery is packaged as something quick and tidy. Books and courses promise hacks, formulas, and accelerated paths to expertise. Organizations do the same, embedding expertise into frameworks and competency models. The assumption is straightforward: with enough knowledge, motivation, and repetition, expertise naturally follows.

Not necessarily.

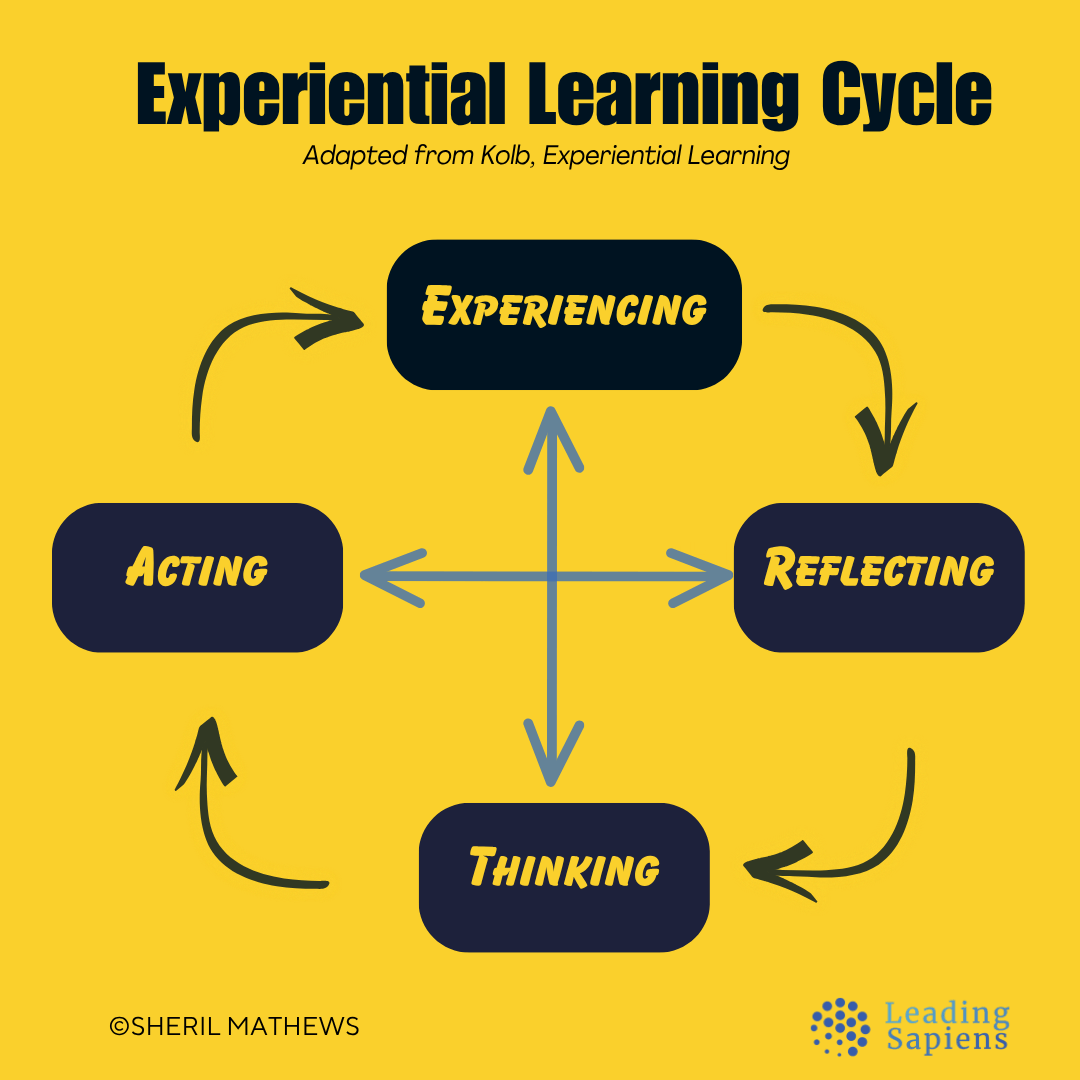

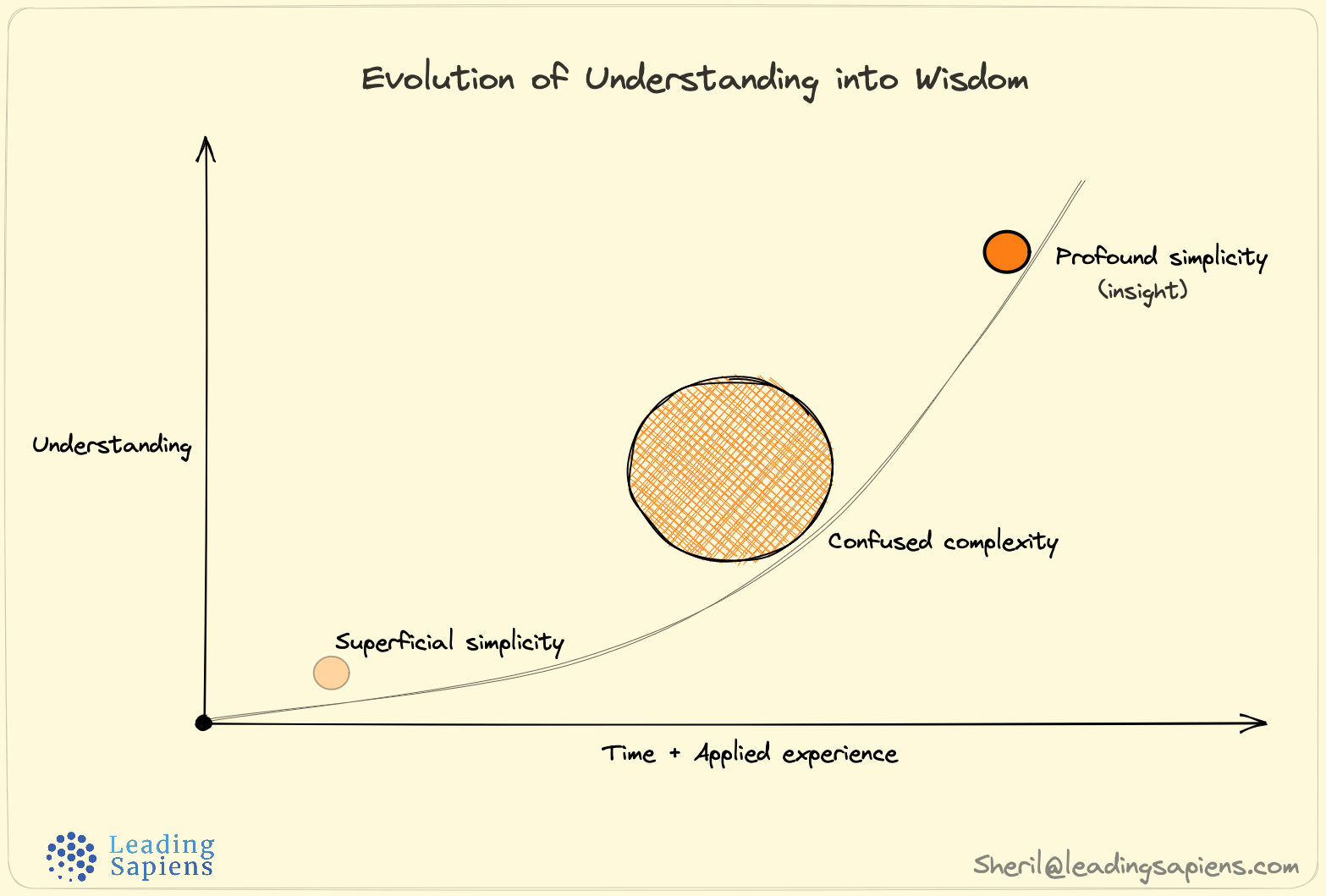

Learning frameworks often treat skill as the accumulation of information and behaviors. The Dreyfus model focuses instead on perception. As skill deepens, action becomes less about conscious analysis and more about immediate recognition. Experts don’t evaluate a situation step by step. They simply see what needs doing.

That nuance is both powerful and difficult to articulate. By the time someone reaches true expertise, they often cannot explain how they know what they know. Knowledge has become tacit, embodied, and deeply situational. This contradicts many of our cultural assumptions. We expect experts to present crisp reasoning, coherent frameworks, and linear explanations. Yet, those traits typically signal competence, not necessarily expertise.

Competence works in stable environments but can misfire in complexity. Beyond a certain point, you need something else: judgment, sensemaking, and what Hubert Dreyfus called “skillful coping.”

Origins of the model

Before going through the five stages of the model, it’s worth understanding why it exists in the first place, and what problem it was originally trying to solve.

In the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force faced a puzzling contradiction. Its best pilots routinely violated the very rules they were trained to follow. In high-stakes situations, they made rapid, decisive moves that couldn’t be explained by checklists or doctrine. When asked how they knew to take a certain action, many simply shrugged and said, “I just knew.”

The Air Force turned to an unlikely pair at UC Berkeley: Hubert Dreyfus, a philosopher of phenomenology, and his brother Stuart, a mathematician. What they uncovered went far beyond aviation. Their research revealed that genuine expertise has little to do with memorizing more information or applying more rules. Instead, it involves a shift in perception. An expert pilot doesn’t read the cockpit; they feel the aircraft, awareness fused with the situation.

These insights became the Dreyfus Model. It challenged the idea that mastery can be reduced to frameworks, checklists, or certifications. As people progress from novice to expert, they don’t just get better at applying rules. They outgrow the need for rules at all.

Their conclusion was radical for its time: human learning isn’t primarily the accumulation of facts. It’s a transformation of how we interpret situations. Beginners break the world into pieces; intermediate performers start recognizing patterns, while experts perceive the entire situation at once and respond fluidly. They don’t follow rules; they inhabit situations.

This cut against decades of rule-based thinking. It also challenged the assumptions of corporate training, which was—and largely still is—built around the idea that performance improves by adding more structure, guidance, and steps.

The Dreyfus model argued the opposite: the highest levels of performance emerges when structure falls away.

Let’s take a closer look at each of the five stages.

Five Stages of the Dreyfus Model

1. Novice

At the novice stage, the learner enters a domain with no relevant experience. They don’t yet know how to discern what matters and what doesn’t, so they rely on explicit, context-free rules handed down by others.

They don’t see situations but steps. The priority is compliance, not understanding. Correctness means sticking to the script. Novices operate entirely through rule-following. And the rules are: taught explicitly, applied rigidly, and independent of context.

Because nothing feels familiar, they treat all elements as equally important. This leads to a form of information overload: trying to track everything, but lacking the discernment to know what can be safely ignored. Performance is cautious, rigid, and often brittle in real-world conditions.

When the rules fail to fit the situation, they’re stuck: they either freeze, or ask for help.

A novice chess player knows the rules: how pawns move, how to castle, or how to capture pieces. They may memorize basic openings, but cannot yet recognize threats, spot opportunities, or plan sequences. They play move by move without an overarching strategy.

The novice benefits most from:

- Simple, clear-cut rules with minimal ambiguity.

- Error-free practice environments that minimize overwhelm.

- Repetition to build comfort with procedures.

Progress to the next stage begins when rules start to feel intuitive, when real experience begins to erode the illusion that all situations can be addressed by generic instructions.

2. Advanced Beginner

The advanced beginner starts to build a bank of recognizable features. They no longer follow rules blindly. Instead, they draw on specific experiences and precedents.

They begin to develop situational memory, noticing repeating patterns and associating them with outcomes. However, these insights are often fragmentary. They don’t yet have a bird’s-eye view, but have seen enough to say, “This reminds me of that other time when…”

The advanced beginner knows something about some situations, but doesn’t yet know how much they know or whether it actually applies. They operate through concrete recollection rather than abstraction. This makes them flexible, but also inconsistent. One memory may cause them to overgeneralize; another might lead them to miss subtle differences.

Advanced beginners combine rule-following with spot-memory. They:

- Remember what seemed to work last time.

- Begin to recognize contextual cues (but can’t yet interpret them).

- Experiment, sometimes successfully, sometimes not.

- Are more improvisational than novices, but still lack the structure to reliably assess whether their responses are good, lucky, or risky.

The advanced chess player begins to spot basic tactical motifs like forks and pins. They can sometimes set traps or avoid blunders, but don’t yet grasp larger strategic patterns. They know “that kind of setup” usually leads to trouble, but aren’t sure why.

Advanced beginners need:

- Exposure to varied examples so they can compare and contrast.

- Guided feedback to help discriminate signal from noise.

- Support in building relevance, so they can learn which details to attend to and what to ignore.

At this stage, the risk is misattribution. Because they can now recall more, they often assign significance too quickly or try to reuse a tactic in a situation where it doesn’t fit.

To move forward, they must stop collecting fragments and start organizing them into more integrated patterns. That’s the threshold of competence.

3. Competent

The competent performer stands at a turning point in skill acquisition. Where the novice followed rules and the advanced beginner collected fragments, the competent individual begins to construct their own map of the domain. This is the first stage where the learner doesn’t just act but owns their decisions.

They now grasp situations as structured wholes: meaningful configurations oriented toward goals, instead of just familiar patterns. Perspective becomes decisional: “What am I trying to accomplish, and what’s the best course of action?” Plans start to matter because the performer now has the capacity to construct and commit to them.

This commitment comes with a cost, however. With agency comes anxiety: Where earlier stages allowed for deflection (“I just followed the rules”), the competent performer begins to feel accountable. Choices are no longer obvious, and outcomes start to carry emotional weight.

The competent performer operates with conscious deliberation. Their decisions are:

- Goal-oriented, organized around long-term aims.

- Analytical, involving comparison of alternatives.

- Plan-driven, consisting of steps that are evaluated for fit and outcome.

Unlike advanced beginners, competent performers don’t merely recall past examples but construct responses for the current situation. They use principles, heuristics, and mental simulations, but must still think them through.

They begin to develop personal maxims: if-then rules shaped by experience. But these maxims are still considered, not yet internalized or felt.

A competent chess player recognizes not just tactical patterns but also starts formulating plans such as building pressure on the king-side or controlling the center. They visualize several moves ahead, weigh consequences, and adapt if the opponent responds unexpectedly. They are no longer reacting move by move.

Competent performers grow by engaging with structured complexity. Instead of more rules, they need practice that forces them to navigate uncertainty.

They benefit from:

- Deliberate decision-making under pressure, where they must balance tradeoffs.

- After-action reviews, where they examine not just what they did, but why.

- Incremental autonomy, where they are given responsibility and space to revise their judgments in real time.

This is also where professional identity begins to coalesce. The learner starts to think of themselves as “a driver,” “a player,” “a practitioner.” Identity fuels deeper commitment but also heightens self-evaluation.

Competence is a productive plateau but also a fragile one. Some performers stall here: gaining confidence in analysis, but avoiding the deeper perceptual and intuitive work required to move further.

To break through, they must begin to see situations as not just solvable, but also interpretable. That requires relinquishing control over every variable and learning to read the whole, not just manage the parts.

4. Proficient

The proficient performer experiences a fundamental shift: situations now speak for themselves.

Where earlier stages required effortful rule application or analytical planning, the proficient individual perceives meaning directly from the flow of events. They don’t have to reconstruct the whole from pieces; the pattern arrives pre-assembled, though not always with full clarity.

They grasp the situation as a coherent whole, informed by extensive experience. But while their perception is largely intuitive, response is still partially analytical. They may understand what’s going on almost immediately, but still pause to reason through how to act.

Perception becomes fluid and context-sensitive. Judgment is faster, but not yet automatic. They no longer rely on decomposing the situation into steps. Instead, they draw on maxims: rich, situation-sensitive guidelines that help them frame what’s happening. Instead of rigid rules, these are contextual prompts, honed by experience.

The proficient performer’s decisions are shaped by a blend of intuition and analysis. They intuitively grasp what the situation is about, but still need to deliberate about how best to respond.

This stage is defined by pattern recognition coupled with partial deliberation. They feel the direction things are going — they know when something is “off,” or when a subtle opportunity is emerging — but aren’t yet fully absorbed in the action.

Importantly, they can detect deviations from expectations without being told. Their mental model now includes anticipated futures, so when the future starts to unfold differently, they feel it before they can articulate it.

A proficient chess player quickly senses the strategic potential of a position: perhaps recognizing that the opponent’s king is subtly exposed or that a positional imbalance can be exploited. They deliberate on concrete variations, but exploration is now guided by intuition instead of just blind analysis.

Proficient performers benefit from:

- Case-based reflection, especially those that highlight when their intuitions served them well, or failed them.

- Mentoring conversations where experts help them articulate their fuzzy perceptions into clearer reasoning.

- Exposure to edge cases where expected patterns don’t quite apply.

At this stage, the main challenge is calibrating intuition. The performer begins to trust their gut, but that trust can lead to overreach if experience hasn’t yet covered enough variation.

To move forward, they must begin to let go of deliberation entirely and act with absorbed responsiveness. That means becoming comfortable knowing more than they can say, and acting from that place.

5. Expert

At the expert level, performance becomes immediate, fluid, and embodied. The expert doesn’t choose a response; they simply act. Action is not based on rules, calculations, or even conscious deliberation. It emerges from deep familiarity with the situation itself.

This is the culmination of years of exposure, feedback, and reflection. Instead of mere problems, they see meaningful patterns, deviations, tensions, and affordances. These are not inferred, but directly perceived.

Responses are deeply context-sensitive and often difficult to articulate. In fact, much of what experts do cannot be fully explained, even by themselves.

Crucially, skill is not a matter of automaticity or repetition. It’s adaptive improvisation: a subtle dance with the situation as it unfolds, adjusting moment to moment with no need for conscious reconstruction.

The expert:

- Does not deliberate in typical cases, they respond.

- Recognizes anomalies instantly and adapts without pause.

- Can explain their thinking if required, but typically only after the fact.

Expertise is not an absence of thinking but a different kind. It’s embodied, situated, and tacit. Experts operate from an internal library of experiential understanding that has become second nature. Their actions feel obvious to them but opaque to others.

The expert chess player sees a position and instantly feels that something is wrong — perhaps a subtle mis-coordination between the opponent’s pieces. They don’t need to calculate dozens of moves to verify it; intuition tells them where the vulnerability lies. The subsequent moves are shaped by that recognition, surprising even to them in retrospect.

At this stage, learning looks very different. It’s less about acquiring new rules and more about:

- Refining discernment, especially in ambiguous or high-stakes situations.

- Sharpening adaptability to novel or unstable conditions.

- Translating tacit knowledge into teachable insights for others; a process that often requires slowing down and reflecting on what has become second nature.

The challenge here is to stay reflective. Expertise can lead to overconfidence or complacency. What experts gain in fluidity, they can lose in conscious awareness. So the expert must cultivate humility: noticing when old intuitions no longer fit new contexts.

Key Concepts and Underlying Dynamics

To understand the Dreyfus model as more than a staircase of competence, we need to examine the mechanisms underlying the process of skill acquisition.

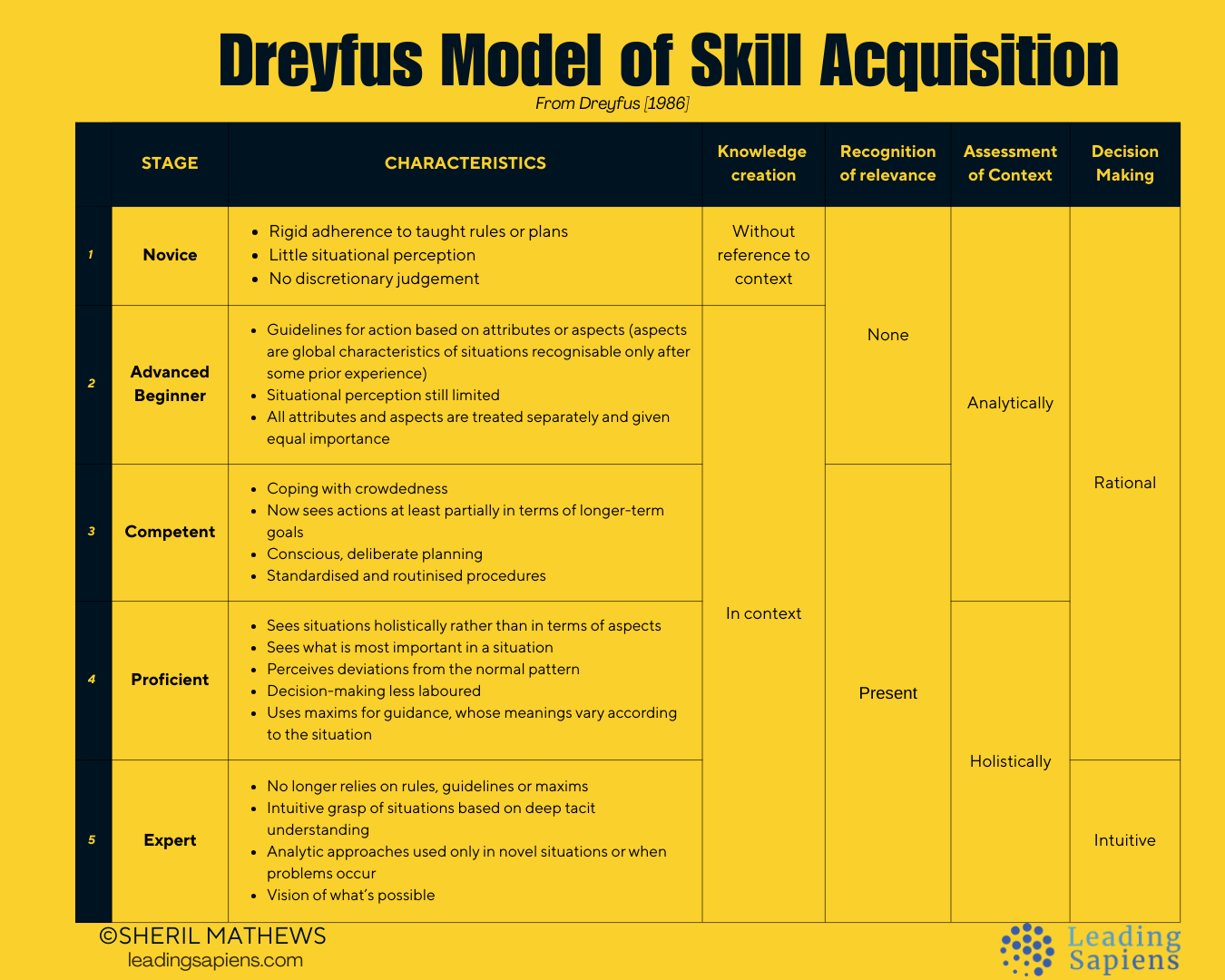

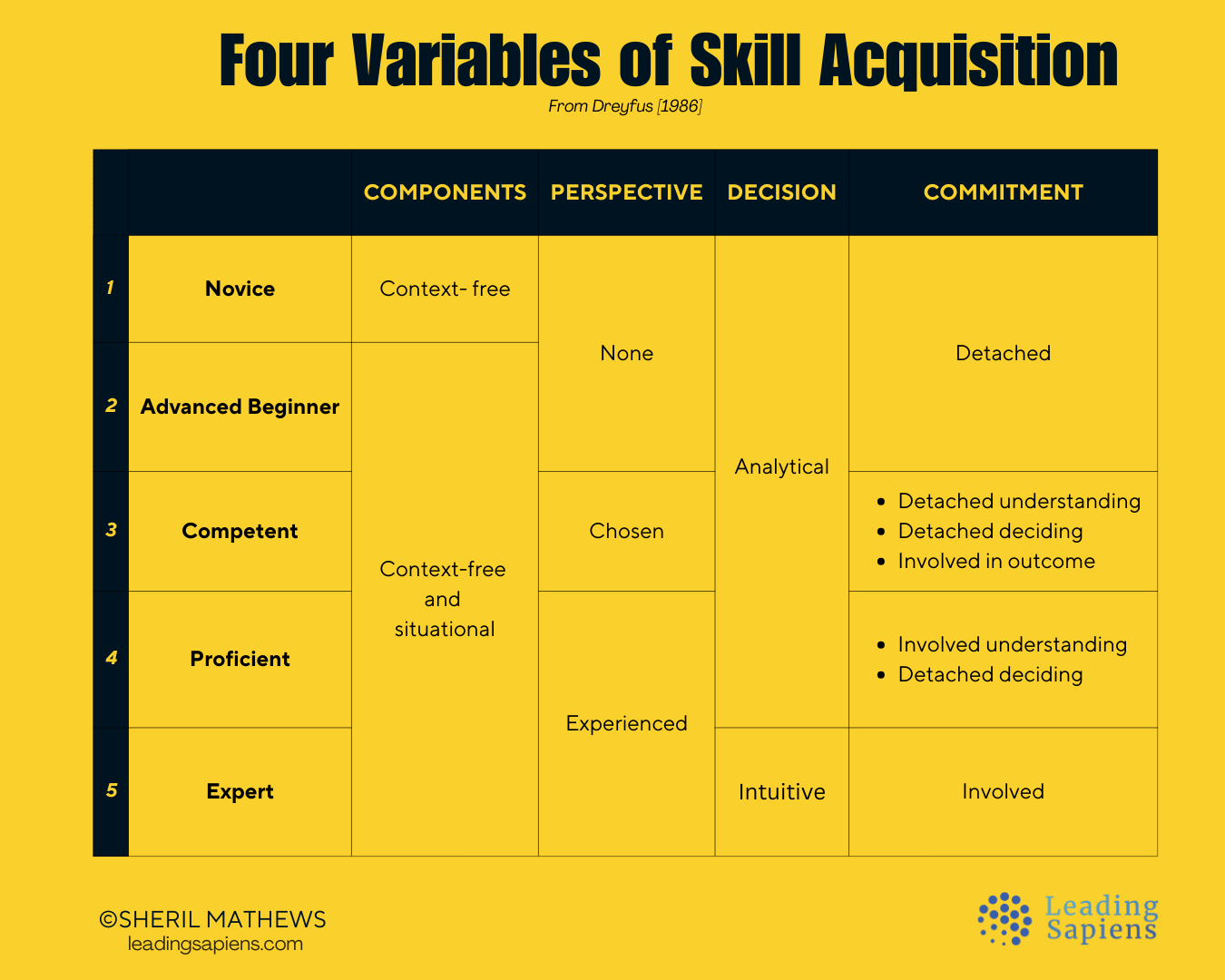

Four Interrelated Variables

Across each stage of development, the learner’s engagement with the world is shaped by changes in four key dimensions: components, perspective, decision, and commitment. Taken together, these dimensions chart a transformation in how we perceive, engage with, and make sense of our environment.

Components

At early stages, the learner sees the world as fragmented composed of isolated, context-free elements. These are “facts,” “rules,” or “features” to be memorized or matched. As skill develops, those discrete components fuse into meaningful patterns, shaped by prior experience. What begins as abstraction becomes situated reality. The learner stops seeing pieces and starts seeing wholes.

Perspective

Novices must choose where to direct their attention, often arbitrarily or according to instruction. The world presents too much information, and the novice lacks the filter to know what matters. Over time, perspective becomes guided by experience and relevance. Experts do not merely see more; they see what matters, often instantly.

Decision

In early stages, decisions are made analytically, by applying rules or procedures. As experience deepens, decisions shift toward recognition-based responses. The competent performer compares options; the proficient performer sees patterns; the expert responds without conscious calculation. Decision-making becomes less a matter of choice, more a matter of “attunement”.

Commitment

Perhaps the most under-appreciated variable, commitment marks the emotional investment in the task. While novices follow instructions and competent performers own their choices, expert performers are fully immersed. They’re involved, not just executing. They feel what’s at stake, and that engagement feeds learning.

Knowing How vs. Knowing That

A central distinction in the Dreyfus model is between knowing that (explicit, declarative knowledge) and knowing how (tacit, embodied skill). This is a fundamental reorientation of what counts as understanding.

Knowing that involves facts, concepts, procedures. Things that can be stated, tested, and taught. Knowing how involves embodied responsiveness, the ability to act skillfully without necessarily being able to articulate why.

The model asserts that true expertise resides in knowing how. It’s what allows a nurse to feel something’s wrong with a patient even when all the vitals are normal, or a chess player to spot a subtle weakness in a position with no clear calculation.

Tacit capacity is not inferior to rational knowledge. It’s often more powerful, especially in fast-moving, uncertain, ambiguous contexts.

Importantly, the Dreyfuses argue that knowing how is not reducible to knowing that. You cannot simply add more information to reach mastery. Expertise requires embodied experience from repeated exposure to real contexts, with consequences and feedback.

What Intuition Really Means

In the Dreyfus model, intuition is not guesswork, magic, or irrationality. It’s a precise term describing a particular kind of understanding:

Intuition is the effortless recognition of similarity to past patterns of experience. [1]

It’s built through accumulated familiarity, not logical derivation. Where the novice reasons, the expert recognizes. Intuition allows you to grasp the feel of a situation without breaking it down into parts.

The expert’s intuition is reliable because it has been forged through repeated exposure to variation, feedback, and consequence. It’s anchored in deep experience.

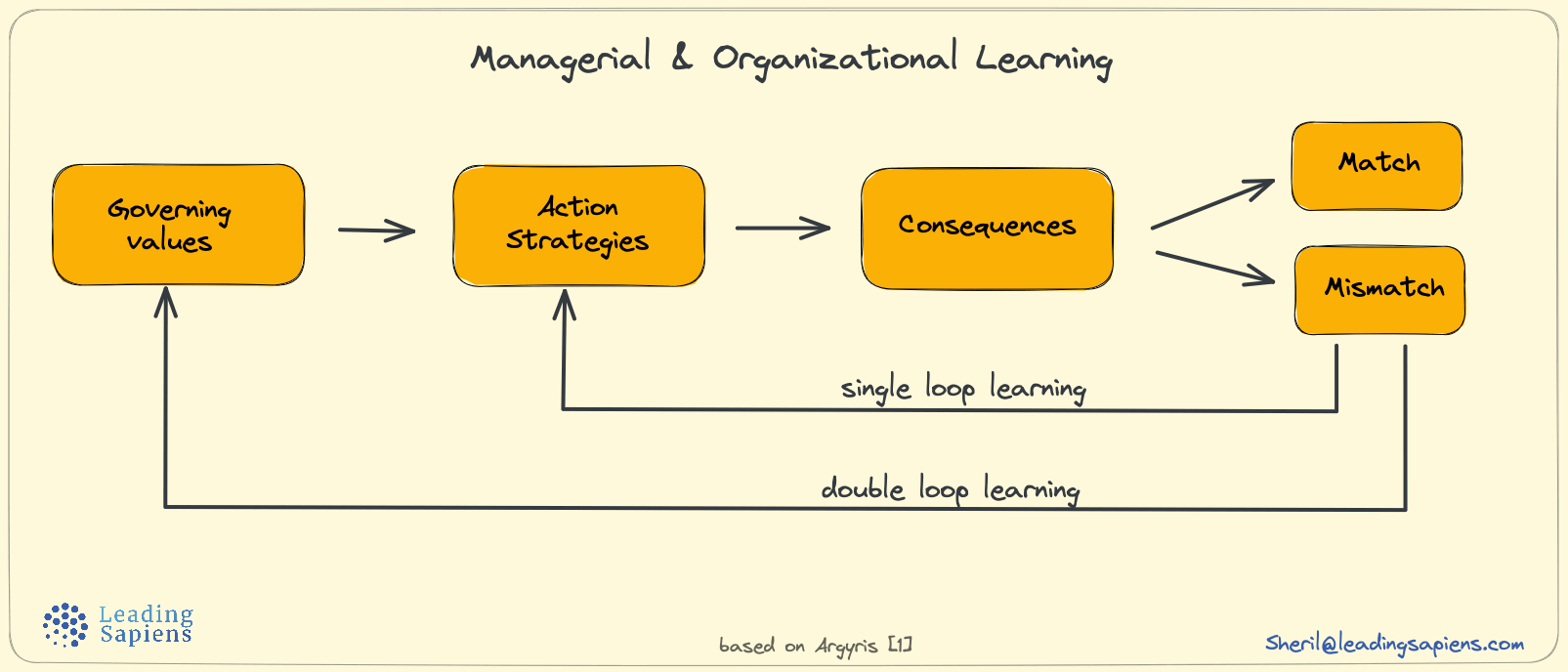

The Role of Emotion in Learning

Unlike other models of expertise, the Dreyfus framework places serious weight on emotion — as information, not distraction.

Emotional responses — anxiety, pride, regret, confidence — are integral to learning. When a competent performer’s plan fails, the sting of that failure sharpens attention. When a judgment proves correct, satisfaction reinforces the pattern.

Experience, in this model, is not simply time spent in a role. It is:

The refinement of preconceived notions through encounters with actual situations that add nuance, texture, and divergence to theory. [1]

Emotion is the mechanism by which those nuances are encoded, and often what marks the transition from abstract knowledge to lived understanding.

Expert Deliberation Isn’t Absent but Transformed

One misconception is that experts don’t think, but act purely on instinct. The Dreyfus model nuances this: in most situations, experts act intuitively, but they can deliberate when necessary.

However, their deliberation is not the rule-application of novices. It’s a reflective process of:

- Re-experiencing a case to make sense of what went wrong.

- Noticing elements that were overlooked.

- Challenging their framing.

- Re-training their intuition through structured exposure or critical questioning.

Deliberation becomes a way to tune intuition, not replace it.

This has implications for leadership, coaching, and use of AI — where deliberate reflection and intuitive fluency must co-exist in high-stakes decision-making.

Why the Dreyfus Model is still relevant

Organizations like clarity with predictable steps and clear outcomes. They prize what they can measure.

That’s why even today, most organizations are designed around what the Dreyfus model would describe as competent-level logic: deliberate analysis, structured planning, and the formal application of frameworks. This is the third stage of skill acquisition where people begin to take responsibility for their decisions but still rely on decomposing problems into parts, evaluating options, and choosing the “best” course of action. It’s the domain of SOPs, dashboards, process improvements, and rational planning.

It’s also the level at which performance is visible and explainable. That makes it highly scalable, trainable, and promotable, which is precisely why many systems stop there. Competent-level behavior is easy to monitor, standardize, and reward. So companies build entire infrastructures from job descriptions to development programs around this kind of logic.

But competence isn’t expertise.

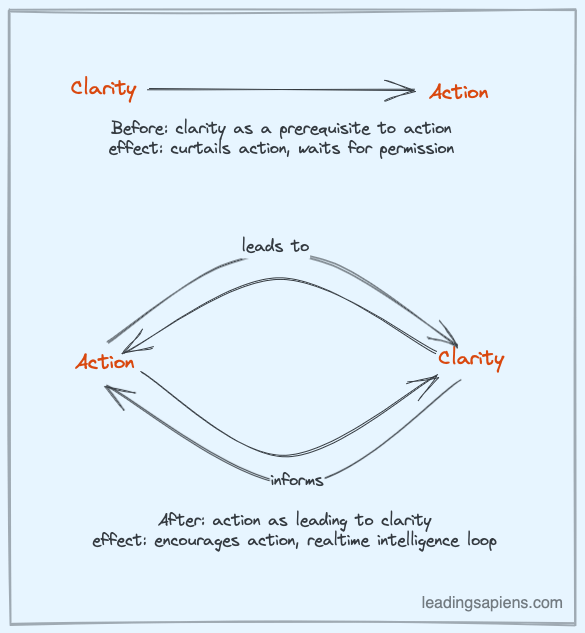

In complex, fast-moving environments, competent-level reasoning often breaks down. Linear logic struggles to keep up and rule-based planning however sophisticated becomes brittle.

What’s required isn’t more analysis but judgment. The kind that only comes from in-depth experience and intuitive perception, and exactly what the model describes in its final two stages.

But those stages are frequently undervalued or invisible in organizations. Experts don’t always follow the process. They deviate, improvise, and “just know.” Which makes it harder to train, manage, and replicate.

The Dreyfus model is not simply a learning ladder or a maturity model. It’s a deep map of how we humans move from rigidity to fluidity, and what must be unlearned along the way.

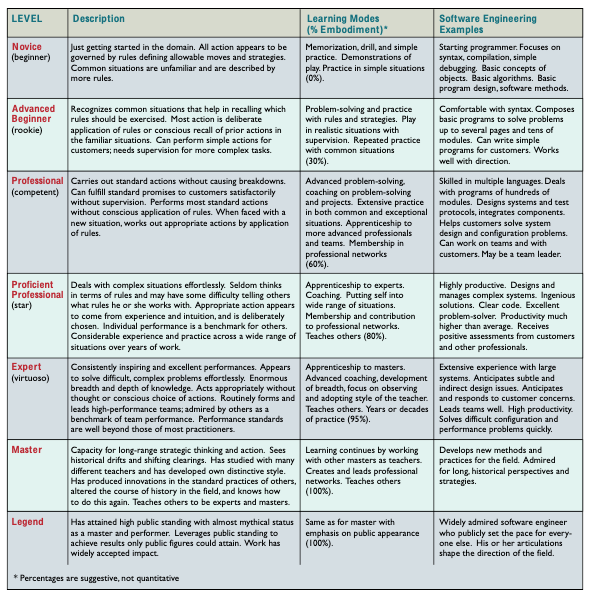

Dreyfus Model - An Example

Below is an example of the Dreyfus Model applied to an entire arc of a career, developed by Peter Denning. [5]

Related Reading on Learning

Sources and references

- Dreyfus, Hubert L., & Dreyfus, Stuart E. (1986). Mind Over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer.

- Dreyfus, Stuart E. (2004). The Five-Stage Model of Adult Skill Acquisition.

- Vanderburg, Willem H. (2004). The Human Skill-Acquisition Model of Stuart Dreyfus: Its Relevance for the Design of Engineering Education.

- Dreyfus, Hubert L. (1979). What Computers Can’t Do: The Limits of Artificial Intelligence.

- Peter J Denning. (2002).The profession of IT: Career redux