Why do we feel an instinctive sense of trust when interacting with some people, while others leave us with a vague sense of unease, as if interacting with a polished but hollow shell? This is especially relevant to effective leadership —you might be saying all the right things, but others experience you as fragmented or off.

Leaders are expected to maintain a calm, professional demeanor. This leads many to wear masks of certainty and authority, believing that to reveal a moment of doubt or a flicker of irritation would be to lose control.

Maintaining poise is of course important. But that’s only one dimension. Poise that’s out of context and out of touch turns into a perma-facade that’s a drag on leadership.

It’s because we are evolutionarily primed to detect a failure of what Carl Rogers called “congruence” — unity between our internal experience and what we project. According to him, the most powerful state a human being can inhabit is not one of calculated control, but congruence — a state of being integrated and whole, "all in one piece”. Nowhere is this more applicable than in leadership.

While congruence is often simplified as "being yourself" or the more cliched “authentic”, in Rogers’ framing it’s a more nuanced, three-part alignment that’s a lifelong leadership challenge.

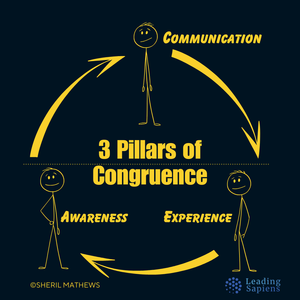

The Three Pillars of Congruence

Congruence is the accurate matching of physiological experiencing with awareness, and the matching of these with what is communicated.

— Carl Rogers

Rogers defined congruence as a state of internal consistency that requires an the matching of three distinct levels: experience, awareness, and communication.

Instead of constantly presenting a curated "professional" image, congruence requires being unified and integrated in the moment. This means whatever we’re experiencing is accurately reflected in our consciousness and communication.

When an infant feels hunger (experience), their awareness matches it, and their cry (communication) is perfectly aligned with that hunger. The infant is transparently themselves because they are unified all the way through. In contrast, adults often suffer from a mismatch between these levels.

This is why an infant’s cry feels much more real than a CEO’s well-rehearsed apology.

1. Experience (visceral level)

The first level is the actual physiological and visceral events occurring within us. It’s the "gut-level" reaction that happens before we’ve even put a name to it. It’s everything going on at any given moment that’s available to the senses, whether it’s the apprehension that feels like a chill inside, the heat of anger, or the lightness of contentment.

Because this flow is a biological reality, we can use it as a referent to check against our mental constructions.

2. Awareness (symbolic level)

The second process is the symbolization of our experience where the raw data of experience is represented in consciousness. Awareness is our mind’s representation of the visceral flow.

Congruence happens when these symbols accurately match our real experience. When we’re congruent, there are no barriers or inhibitions preventing the full experiencing of whatever is naturally present.

When these two processes fail to match — when there’s a mismatch between experience and awareness — Rogers calls it defensiveness or denial to awareness.

For instance, a manager whose face is flushed and voice is shaking with rage (experience), yet insists with evident sincerity that they’re not angry at all (awareness). Their physiological experience (anger) is not accurately represented in their awareness. They aren't necessarily lying but simply unable to access the truth of their own internal state.

When leaders are incongruent, communication becomes contradictory and confusing to others.

3. Communication (expressive level)

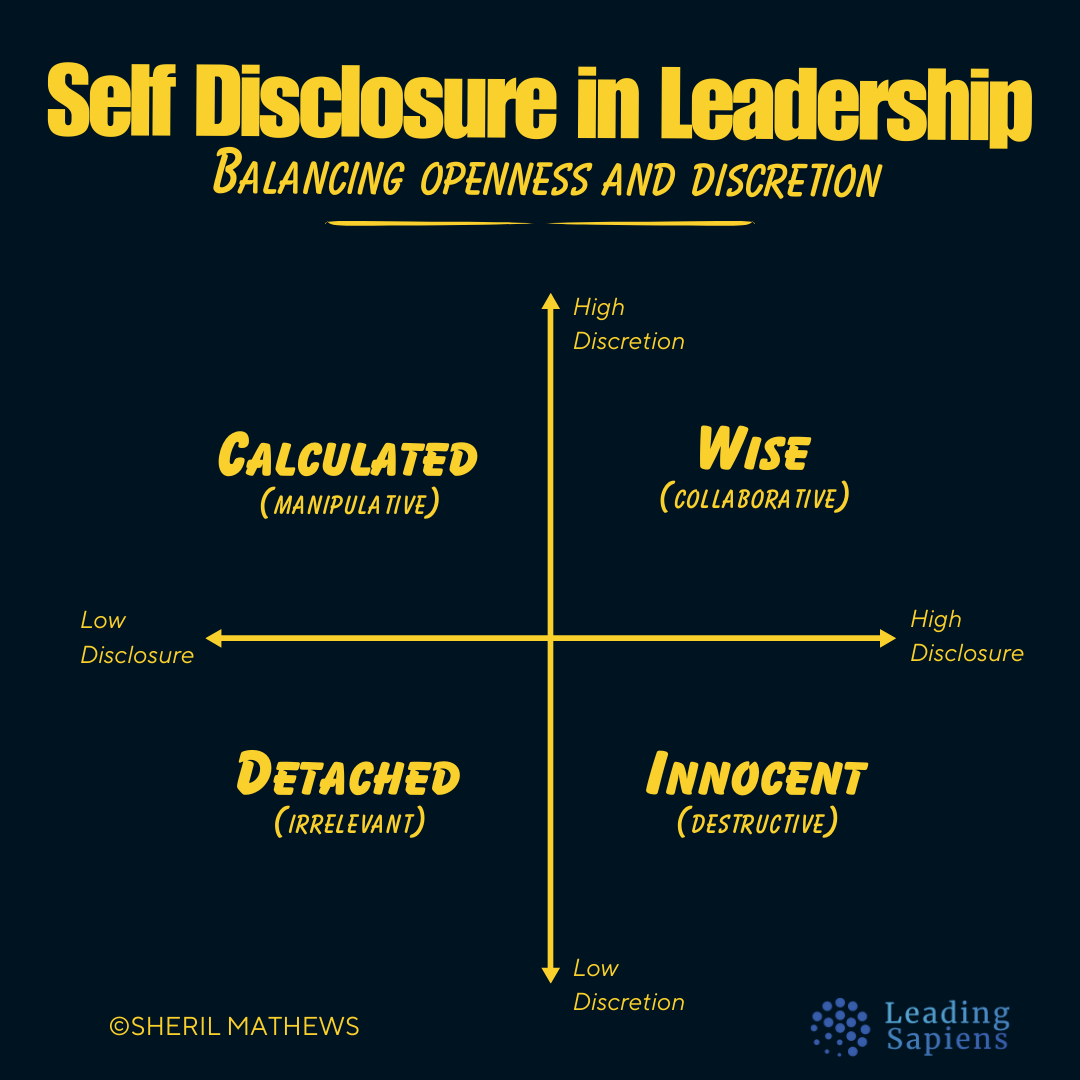

Communication is the outward expression — the words, tone, behavior, and gestures used to signal our experience and awareness to others. To be fully congruent, what we say to others must match both what we are thinking (awareness) and feeling (experience).

Rogers used the term "transparent" to describe this state: one makes themselves see-through to others, holding nothing back. What’s present in one’s awareness is what’s shared with the world.

When we’re aware of our internal state but choose to project a different image, it’s a falseness or deceit. A classic example is the host consciously aware of their boredom but who tells their guest, "I enjoyed this evening so much". Here, the person knows their internal truth but chooses to project a front. Internal alignment is present, but the external communication is a facade.

The Congruent Self

Why is internal alignment vital to leadership? When we’re unaware of our own experience—such as annoyance or skepticism—communication becomes contradictory.

On the surface your words may convey support or acceptance. But subsurface subtle cues, tone, or body language communicate the hidden annoyance. This split creates confusion. Even if the other person cannot quite name what is wrong, they become distrustful because they sense a reality the leader is denying.

When all three processes—experience, awareness, and communication—are in alignment, we’re completely in one piece aka congruent. This unity makes communication clear and believable to others. Because all cues from speech, tone, and gesture spring from a single source of truth, others experience us as unambiguous.

Rogers considered congruence the most critical of his "core conditions for change". He formulated what he called a "General Law" to explain the reciprocal nature of this state:

The more a person (X) is congruent in a relationship, the clearer their communication becomes because all cues—speech, tone, and gesture—are unified. This clarity makes it more likely that the other person (Y) will feel "empathically understood". When Y feels understood, their own defensiveness decreases, allowing them to communicate more congruently in return.

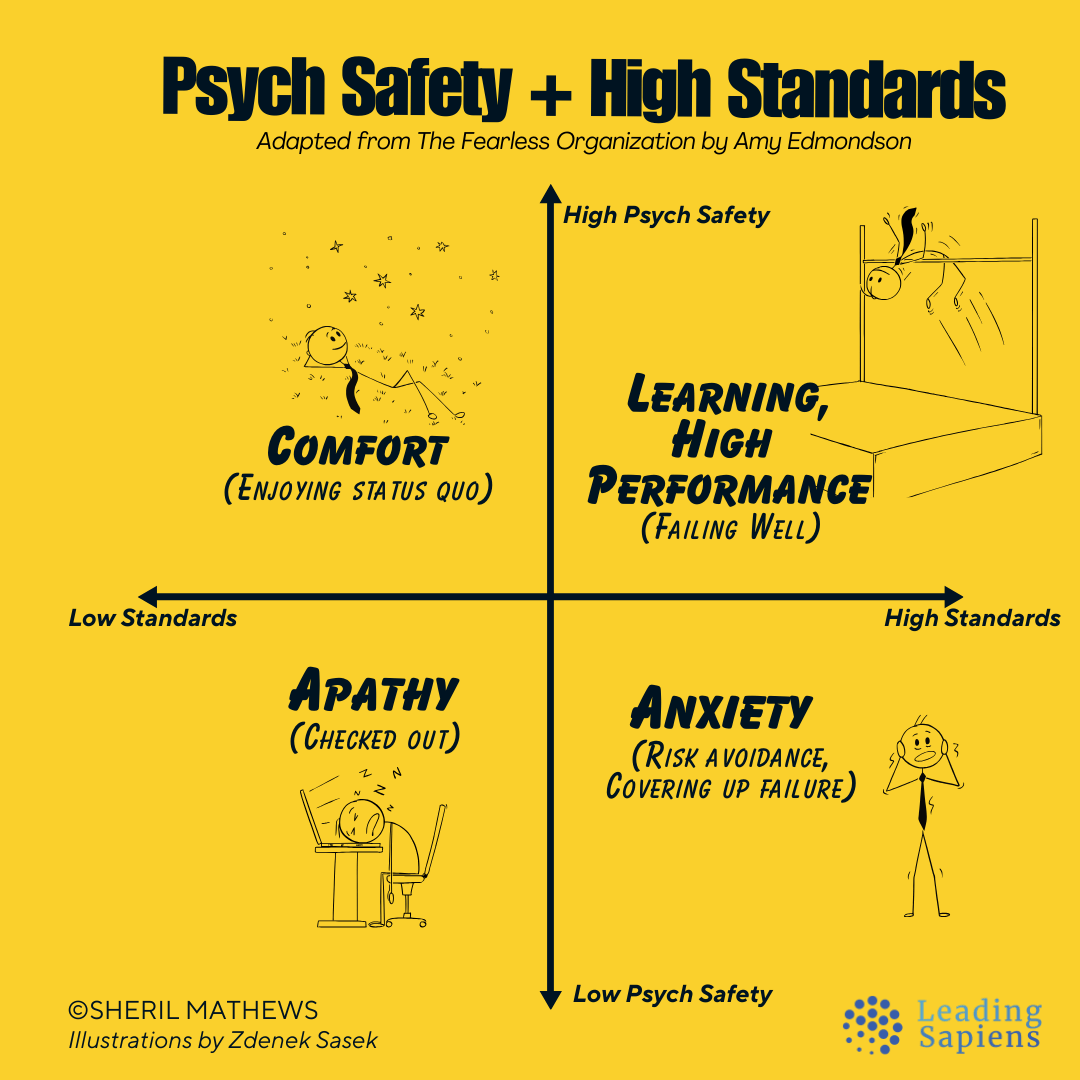

Thus, congruence is contagious and key to effective leadership. A congruent leader creates a climate of growth where others feel safe enough to drop their own masks. Conversely, incongruence is equally contagious but negatively.

By being dependably real across all three levels, the congruent person creates a working environment where initiative flows up organically instead of being coerced from the top down.

Congruence is an ongoing, fluid process of revising the self through a constant openness to experience. You’re constantly choosing to risk being seen exactly as you are, rather than as you wish to be perceived.

Implications for Leadership

Traditional notions of leadership assume that leaders must consolidate power and use it to direct, reward, and punish. Rogers’ research and experience, however, showed that this kind of "power over" others often results in a "clutter of facades" that stifles creativity and increases dependency — the opposite of what leaders claim to want.

Congruence shifts the politics of leadership toward a more genuine stance. Consider the different ways congruence plays into effective leadership.

Facades are stifling

Professional facades are typically used as self-protection by maintaining distance and authority. While many leaders want to be genuine, in actual practice they fall far short because they prioritize these techniques over personal realness.

But facades are unsustainable and counter-productive in the long run.

Because our bodies and brains are built for congruence, it requires significant cognitive effort to maintain facades. When we try to cover up parts of ourselves, the incongruence "leaks" through nonverbal cues. We send double messages: words say one thing, but tone, gestures, and vibe leak the unowned feelings beneath the surface.

That’s how incongruence breeds suspicion. Others instinctively sense the discrepancy and become cautious and wary. When leaders aren’t real, people feel unsafe, sensing that the authority figure cannot be fully trusted.

The power of realness

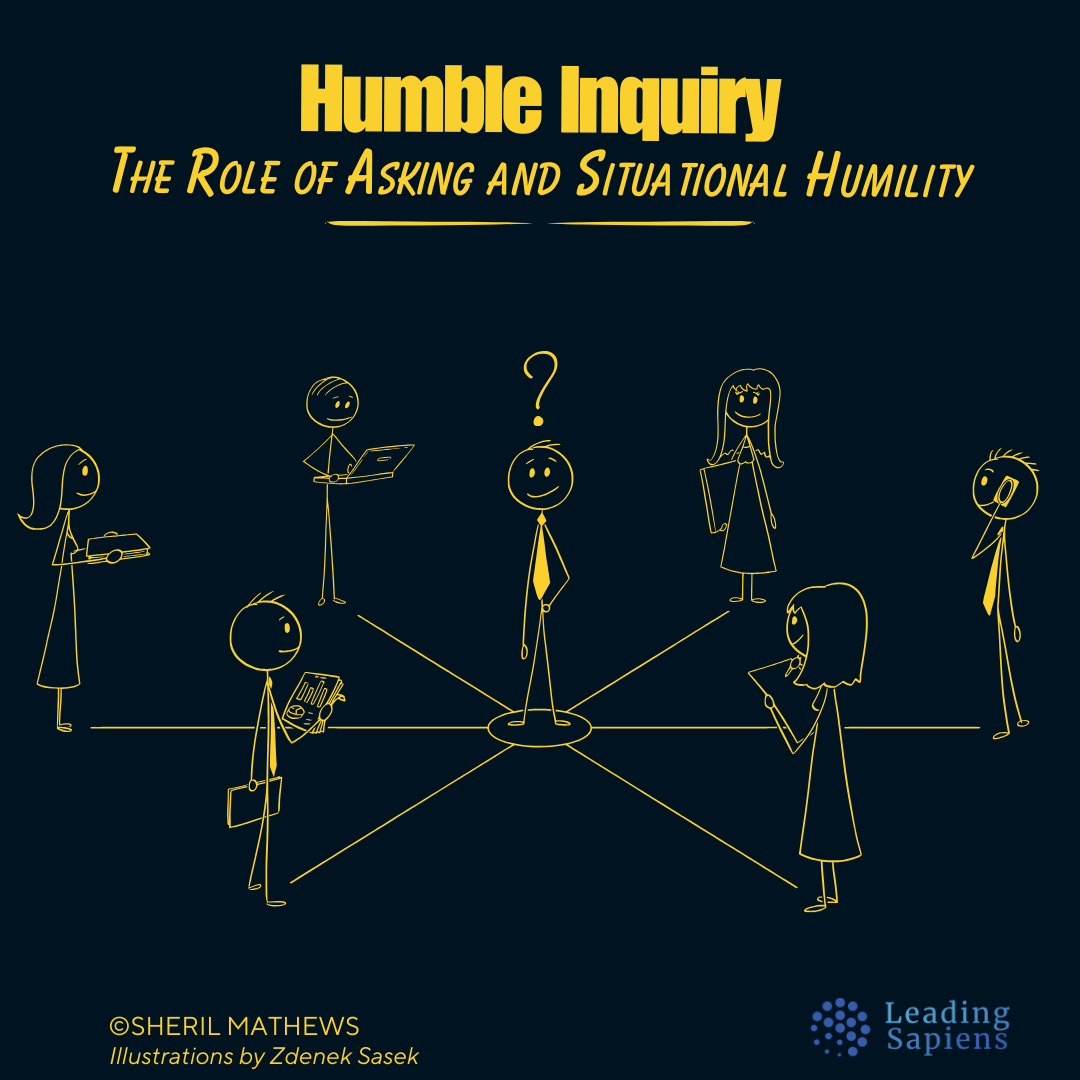

When leaders are congruent, they provide a "discernible reality" that people can relate to. By being "dependably real," the leader removes the threat of themselves as a "potential changer" or evaluator. This empowers others to find their own internal "locus of evaluation".

You aren’t “giving” power to your team per se; rather, you aren’t taking it away to begin with. This enables reciprocity, transparency, and trust:

- The more you’re a real person and avoid self-protective masks, the more others reciprocate and change in a constructive direction.

- When others can see a real person, they drop their own masks.

- Congruence signals that the relationship is being lived, not managed.

Consistency vs. “dependable reality"

A common leadership myth is that being trustworthy requires rigid consistency—always acting the same way regardless of the circumstances. We mistake "trustworthy" for "consistently nice."

But true trustworthiness stems from being dependably real. When annoyed, it is more helpful to own that feeling ("I feel irritated") than to act pleasant while leaking hostility through subtle cues. Others sense this honesty and feel safe to be real themselves.

When leaders act consistently “pleasant” while internally feeling critical or annoyed, they’re being incongruent. While they might be acting as trustworthy, the underlying feelings will eventually be perceived as inconsistency or as inauthentic.

Others sense the gap between the surface behavior and the underlying reality, which undermines your credibility.

Daring to be real

Leading congruently is not merely a technical skill, but an ongoing "existential choice". In every interaction, we face the risk: "Do I dare to communicate the full degree of congruence that I feel?"

We fear that showing cracks in our facade will make us appear weak or inept. However, Rogers’ research showed the opposite: the more someone is themselves, putting up no professional front, the greater the likelihood of constructive change in the other.

True power doesn't come from being perfectly effective, but from being congruent—owning one's feelings, even the difficult ones.

This means, to be effective, leaders must develop the capacity to sense what is happening within themselves at any given moment:

- Acknowledging imperfect feelings like boredom, fear, or rejection.

- Accepting these attitudes as facts and parts of themselves rather than pushing them away to maintain a facade.

- Permitting internal states to show through when appropriate.

It requires two ongoing practices, self-awareness and risk-taking:

- Your ability to be genuine with others is strictly limited by how genuine you are with yourself. This involves a keen awareness of one's own internal structure.

- To be real is to risk being changed. It involves the "anxiety of separateness"—the fear that if we are truly seen as we are, we might be rejected.

Congruence is inextricably linked to Rogers’ most famous quip:

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself as I am, then I change.

When leaders are congruent, relationships become "real" rather than static. By being willing to be themselves, the leader finds that not only do they change, but the people they relate to also begin to change.

In this sense, congruence is the catalyst that allows both parties to move away from "false fronts" and toward a more positive, self-actualizing direction.

Rogers admits that this is a difficult task and one he never fully achieved, yet he viewed it as a prerequisite for facilitating growth in others.

The degree to which one can create a helping relationship is often a direct measure of the growth and congruence we’ve achieved within ourselves.

Genuineness as a political act

It may feel natural to hide our inner experience because we learned to do so as a survival mechanism. Congruence, in contrast, is a trained stance of choosing to align our outer words with inner reality.

In a way, choosing to be genuine is a revolutionary political act. Conventional approaches rely on "power over" others through professional distance and the control of information. To be genuine is to consciously renounce this control.

In this supportive stance, the "actualizing tendency" of the group is released. When leaders own their experiences and uncertainties—teams tend to move away from rigid, "structure-bound" patterns toward a fluid, self-correcting process of discovery.

This is the great, secret might of non-interference expounded by Lao-Tzu:

When actions are performed without unnecessary speech,

People say ‘We did it”.

Further reading

Sources

- Rogers, C. R. A Way of Being.

- Rogers, C. R. On Becoming a Person.

- Rogers, C. R. On Personal Power.