In nature, species that survive aren't the strongest or smartest. They're the most adaptive. When the environment shifts, they don't just work harder, they evolve.

Our work lives follow the same brutal logic. The question isn't whether we're the most talented or hardest working. It's also whether we're adaptive enough.

Adaptive leadership — from the work of Harvard's Ron Heifetz — is a key principle underlying my approach to leadership coaching. Over the summer, I finally got a chance to go through his entire body of work spanning multiple decades. I captured some of what I learned in a series of three articles (links at bottom).

Heifetz borrowed the term "adaptive" from evolutionary biology/psychology. Successful adaptation in nature has three elements:

- Preserve what’s essential.

- Discard what no longer serves.

- Create new capacity for a harsher environment.

Thriving in careers and organizations requires the same. Effective adaptations conserve our values and strengths, prune away patterns holding us back, and generate fresh capacity to operate in new conditions.

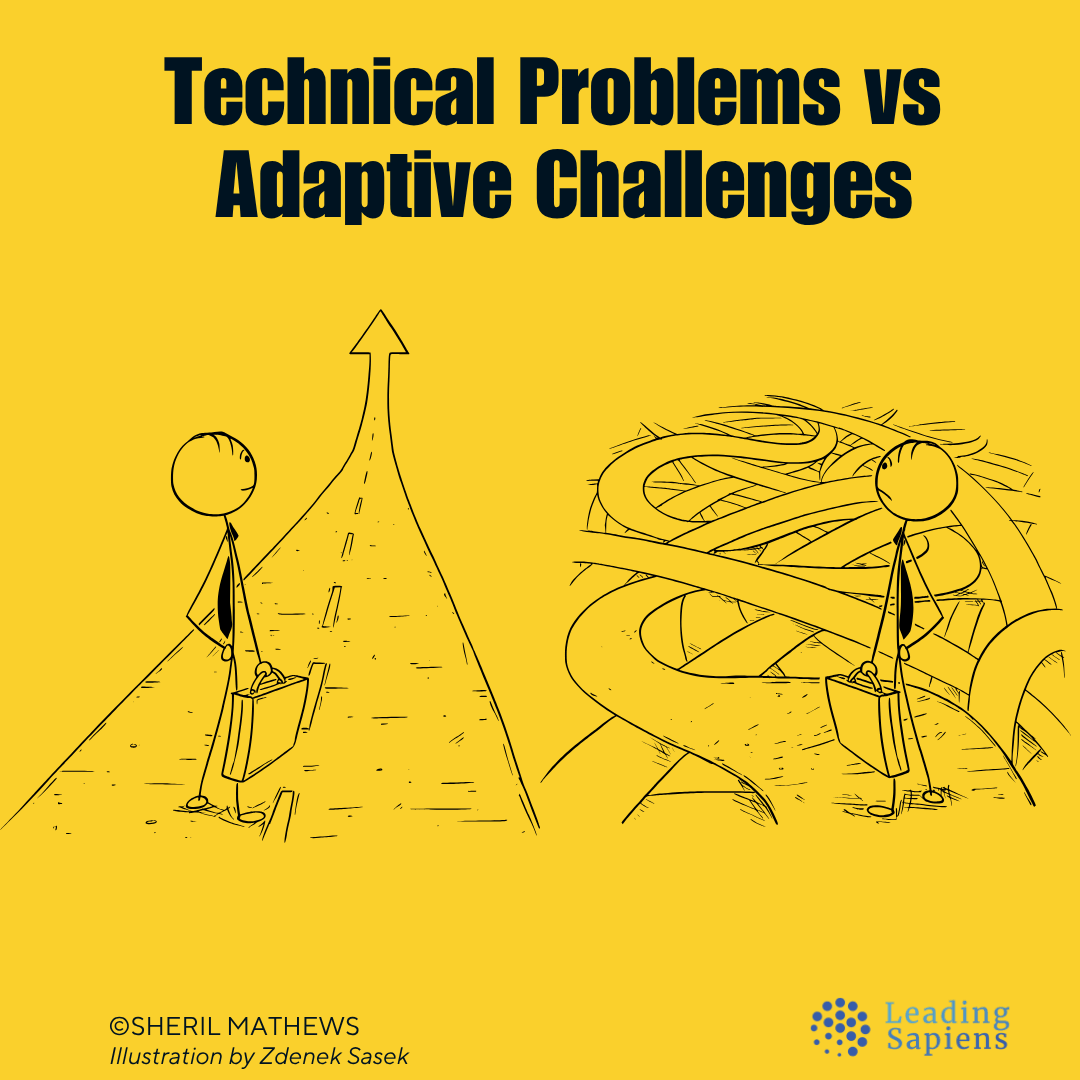

But we usually don't think about work this way. Instead, we treat it like technical problems to solve. We get an MBA, switch companies, or learn another productivity system.

It's like trying to survive climate change by buying a better umbrella.

Because often the challenge isn't technical at all — it's adaptive. An adaptive challenge is when the assumptions we built our work/life around no longer fit; when what once drove us feels hollow.

You can't fix these problems by working harder. They demand something deeper.

Clarifying DNA

Every living system survives by protecting its core DNA while adapting its behavior and responses. Without genetic continuity, it disintegrates. Equally, without adaptive capacity, it becomes fragile when conditions shift.

We face the same challenges. The first step is to know what’s essential vs what’s expendable.

DNA in this context isn’t a resume or title. It’s the combination of values, strengths, and purpose that give us identity. Preserving that core keeps us anchored. Losing sight of it leaves us vulnerable to chasing other people’s scripts: promotions, credentials, or definitions of success that don’t fit.

Adaptation also requires discarding. All of us have habits, assumptions, and roles that once served well but no longer do. The hardest part is recognizing what we must now outgrow.

Sometimes it’s a skill set that kept you competent but now boxes you in. At other times it’s an identity — the expert or the high performer — that once defined us but now limits.

The real challenge is discerning the difference.

In evolution, less than 2% of human DNA shifted from our primate ancestors. Yet that small change unlocked extraordinary new capacities.

Most of what makes you effective can and should be carried forward. But the small fraction that must be released or rearranged often carries the deepest resistance, because it touches what we’ve built our identity and confidence around.

- What part of your DNA must be preserved, regardless of the environment?

- What needs to be discarded, even if it feels like a betrayal of your core identity?

- What new capacities can be created by loosening your grip on what’s familiar?

Thriving doesn’t require wholesale reinvention. Evolution is a lot easier over time than outright revolution.

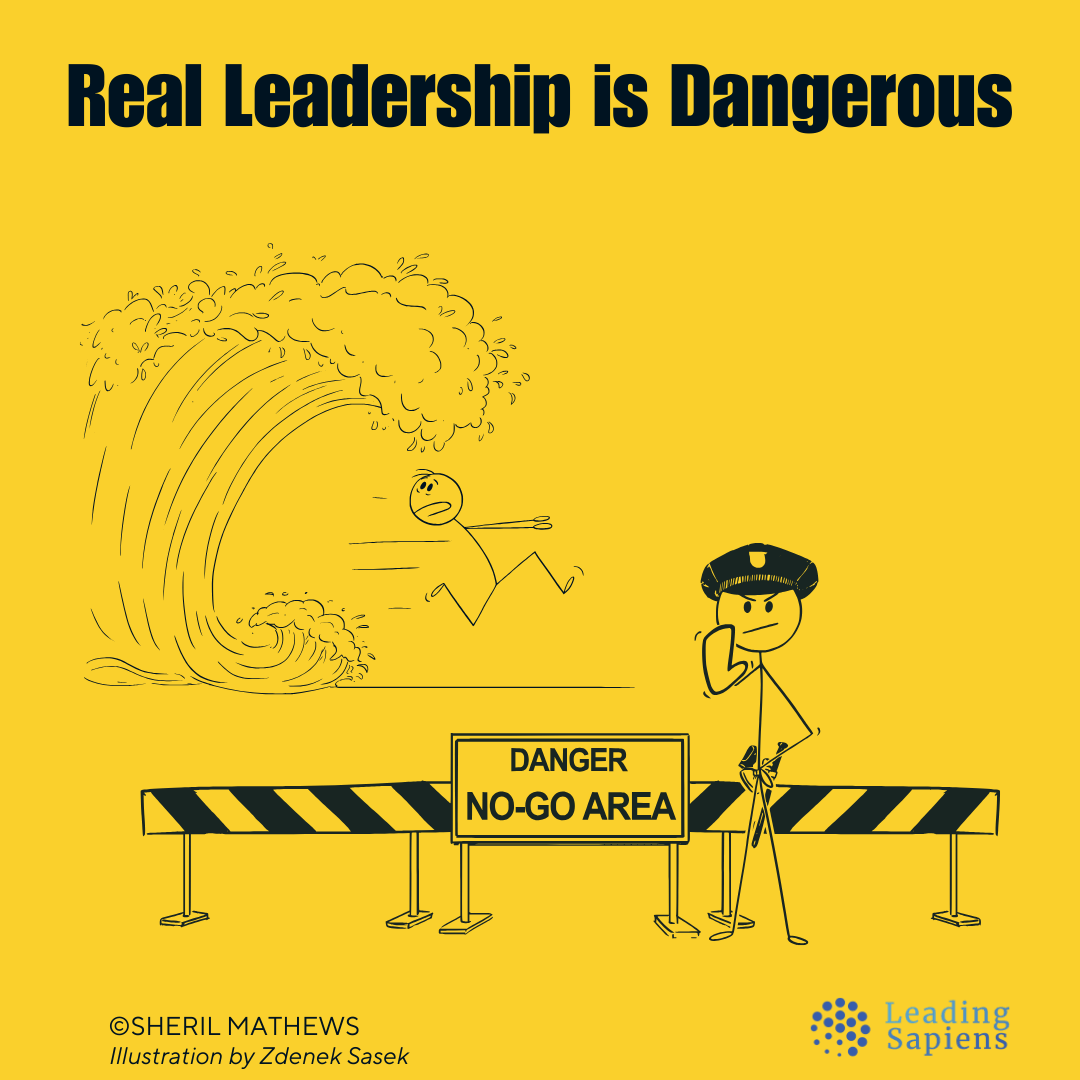

Orchestrating Loss

Every adaptive shift involves loss. Heifetz calls leadership “the art of orchestrating loss at a rate people can absorb.” To adapt, we have to let go of roles and routines that once gave us competence and status.

That’s why resistance is strong. What looks like procrastination, fear of risk, or lack of discipline is often grief in disguise. You’re not just deciding whether to change jobs or retrain in a new field; you’re facing the loss of being the expert and high performer everyone depends on. Adaptive work is painful because it always involves giving up a part of yourself.

The danger is trying to skip this step. It’s common to treat adaptation as addition: a new credential, a side project, or a quick pivot. But without letting go of what no longer fits, the old DNA keeps pulling us back. Real adaptation requires subtraction. It means absorbing the pain of no longer being who we were, in order to create space for who we want to become.

The skill is in pacing losses. Just as effective leaders regulate the heat of adaptive work in organizations, we must regulate our own transitions. If we try to change everything at once, we collapse under the strain. But by avoiding the discomfort altogether, we stay stuck.

Loss is unavoidable. The art is to move incrementally — absorbing it in doses we can metabolize — while still keeping momentum alive.

- What identity/role have I outgrown, but still cling to because it feels safe?

- What loss am I postponing because it feels too threatening?

- What small step can I take to start absorbing loss in a tolerable way?

Building through Experiments

In evolution, adaptation occurs through variation and trial. Countless experiments unfold. 99% or more fail, only a few succeed, but those few set the path for survival.

Our lives are similar. Lasting adaptation doesn’t come from one decisive leap. Instead, it’s often from a series of small, imperfect experiments that gradually open new terrain.

This is where many of us struggle. We want certainty before we act; guarantees that the next role or venture will work. But the adaptive process — by definition — doesn’t have any guarantees. If it was a given, it wouldn’t require adapting. This means moving forward with partial knowledge, learning quickly from what doesn’t work, and treating each step as a probe that yields new information.

In evolution, most variants don’t survive — but the species thrives because the cost of failure is distributed across many experiments. Amazon tests thousands of ideas a year. Most fail. But the few that work — like AWS emerging from an internal tool — generate billions annually.

We need the same logic: spread learning across multiple small bets instead of pinning it all on one radical reinvention.

Over time, this steady rhythm of testing and adjusting builds the capacity to navigate uncertainty that no credential can match.

- Where in my life am I running safe-to-fail experiments?

- How can I lower the stakes of learning to try more without fear of failure?

- How many of my current efforts are genuine probes into new ground versus repetitions of what I already know?

Diversifying the Portfolio

In nature, monocultures are efficient but fragile. They replicate quickly, but when the environment shifts, they go extinct. The Irish Potato Famine killed over a million people because the entire country relied on a single crop variety. When disease struck, there was no backup.

Careers face the same risk. If our identity rests on a single role, employer, or skill set, we’re running a monoculture. It works fine in stable conditions — until it doesn’t. The moment the environment shifts, fragility is exposed.

Robust careers that thrive over time are rarely linear. They're built like healthy ecosystems, drawing strength from redundancy and diversity. Sometimes that diversity is in skills, other times it's in the range of people and communities we're connected to.

Resilience isn’t just personal grit; it’s also structural.

Heifetz writes:

Invest your need for meaning in your life in more than one place. Have what the investment advisers call a balanced portfolio. Shakespeare’s King Lear learned too late that he needed to find meaning and develop skill in his role as a father as well as his role as a king.

Look for meaning in multiple places in both your personal and your professional life. Find it in your community life and in the care you take to exercise your mind and body to keep them both functioning at a high level as you grow older. Find it in the friendships that sustain you at difficult moments and provide a means to share and amplify your life’s joys. Narrowing your life’s meaning to a single sphere, whether it is your work or home or civic or religious life, makes you vulnerable when there are major shifts in the environment in which you are solely invested.

- What part of my career is overexposed — a single skill or identity that everything depends on?

- Where can I build variation to increase my adaptive capacity?

- Who are the voices or networks at the margins that I’ve overlooked, but that could expand future possibilities?

Staying in the Game

Getting started in a new direction is easy. The real challenge is staying with it long enough for change to take effect. In evolution, meaningful adaptation unfolds slowly. Tiny variations accumulate over thousands of cycles before they show up as durable shifts.

But we tend to imagine transformation as a bold leap. I call it "movie time" —the Rocky montage where we emerge stronger in 5 minutes of inspiring music and a solid workout.

Meaningful, sticky growth happens incrementally, through extended periods of ambiguity and effort that feel pointless.

You’ll run failed experiments and spend months where the old identity no longer fits but the new one hasn’t emerged.It’s tempting to retreat to the safety of what we know.

This is why adaptation demands patience and frustration tolerance. It requires "intelligent persistence"—staying in the game long enough for compound effects to take hold. In leadership, this means holding steady while conflict and disequilibrium unfold. At work, this means staying engaged in the long (often slow) arc of change — long enough for small wins to compound into durable capacity.

Truly adaptive change rarely offers the satisfaction of quick closure. Instead, it demands endurance.

- Where am I demanding results faster than the process allows?

- What routines or anchors help me stay steady during periods of uncertainty?

- How can I sustain efforts so I don’t step out of the game just before the gains emerge?

We approach careers like engineers: if something breaks, find the right fix. But life isn’t a machine; it’s a living system. What thrives is what adapts.

The real question then isn’t if we have the perfect plan. It’s whether we adapt when the plan stops working, which it inevitably will.

We ask ourselves, “Am I successful?” as if it’s permanent. But “success” is one fleeting moment — a brief alignment between capabilities, current conditions and outcomes. When conditions shift, today’s success will be irrelevant.

A more relevant question is: Am I adaptive?

Related Reading on Adaptive Leadership

References and Sources

- Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership Without Easy Answers.

- Heifetz, R. A., & Linsky, M. (2002). Leadership on the Line.

- Heifetz, R. A., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership.

- Adaptive Leadership: Making Progress on Intractable Challenges

- The Theory Behind Adaptive Leadership – Cambridge Leadership Associates

- The Work of Leadership – Harvard Business Review